Oh, no. I’m wearing matching pajamas.

And my hair! I have wig hair! It’s totally flat and sweaty!

Everything about this moment is wrong. I’m supposed to be dressed in something glamorous and unique. We’re supposed to be in a crowded room, and his breath is supposed to catch when he sees me. I’ll be laughing, and he’ll be drawn toward me as if by magnetic force. And I’ll be surprised but uninterested to see him. And then Max will show up. Put his arm around me. And I’ll leave with my dignity restored, and Cricket will leave agonizing that he didn’t go for me when he had the chance.

Instead, he’s staring at me with the strangest expression. His brow has creased and his mouth has parted, but the smile has disappeared. It’s his solving-a-difficult-equation face. Why is he giving me his difficult equation face?

“And your family?” he asks. “How are they?”

It’s unnerving. That face.

“Um, they’re good.” I am confident and happy. And over you. Don’t forget, I’m over you. “Andy started his own business. He bakes and delivers these incredible pies, every flavor. It’s doing well. And Nathan is the same. You know. Good.” I glance away, toward the dark street. I wish he’d stop looking at me.

“And Norah?” His question is careful. Delicate.

There’s another awkward silence. Not many people know about Norah, but there are certain things that can’t be hidden from neighbors. Things like my birth mother.

“She’s . . . Norah. She’s in the fortune-telling business now, reading tea leaves.” My face grows warm. How long will we stand here being polite? “She has an apartment.”

“That’s great, Lola. I’m glad to hear it.” And because he’s Cricket, he does sound glad. This is all too weird. “Do you see her often?”

“Not really. I haven’t seen Snoopy at all this year.” I’m not sure why I add that.

“Is he still . . . ?”

I nod. His real name is Jonathan Head, but I’ve never heard anyone call him that. Snoopy met Norah when they were both teenagers. They were also alcoholics, drug addicts, and homeless gutter punks. When he got Norah pregnant, she came to her older brother for help. Nathan. She didn’t want me, but she didn’t want to get an abortion either. And Nathan and Andy, who’d been together for seven years, wanted a child. They adopted me, and Andy changed his last name to Nathan’s so that we’d all have the same one.

But yes. My father Nathan is biologically my uncle.

My parents have tried to help Norah. She’s hasn’t lived on the streets in years—before her apartment, she was in a series of group homes—but she still isn’t exactly the most reliable person I know. The best I can say is that at least she’s sober. And I only see Snoopy every now and then, whenever he rolls into town. He’ll call my parents, we’ll take him out for a burger, and then we won’t hear from him again for months. The homeless move around more than most people realize.

I don’t like to talk about my birth parents.

“I like what you’ve done with your room,” Cricket says suddenly. “The lights are pretty.” He gestures toward the strands of pink and white twinkle lights strung across my ceiling. “And the mannequin heads.”

I have shelves running across the top of my bedroom walls, lined with turquoise mannequin heads. They model my wigs and sunglasses. The walls themselves are plastered with posters of movie costume dramas and glossy black-and-whites of classic actresses. My desk is hot pink with gold glitter, which I threw in while the paint was drying, and the surface is buried underneath open jars of sparkly makeup, bottles of half-dried nail polish, plastic kiddie barrettes, and false eyelashes.

On my bookcase, I have endless cans of spray paint and bundles of hot glue sticks, and my sewing table is collaged with magazine cutouts of Japanese street fashion. Bolts of fabric are stacked precariously on top, and the wall beside it has even more shelves, crammed with glass jars of buttons and thread and needles and zippers. Over my bed, I have a canopy made out of Indian saris and paper umbrellas from Chinatown.

It’s chaotic, but I love it. My bedroom is my sanctuary.

I glance at Cricket’s room. Bare walls, bare floor. Empty. He acknowledges my gaze. “Not what it used to be, is it?” he asks.

Before they moved, it was as cluttered as my own. Coffee canisters filled with gears and cogs and nuts and wheels and bolts. Scribbled blueprints taped up beside star charts and the periodic table. Lightbulbs and copper wire and disassembled clocks. And always the Rube Goldberg machines.

Rube was famous for drawing those cartoons of complex machines performing simple tasks. You know, where you pull the string so that the boot kicks over the cup, which releases the ball, which lands in the track, which rolls onto the teeter-totter, which releases the hammer that turns off your light switch? That was Cricket’s bedroom.

I give him a wary smile. “It’s a little different, CGB.”

“You remember my middle name?” His eyebrows shoot up in surprise.

“It’s not like it’s easy to forget, Cricket Graham Bell.”

Yeah. The Bell family is THAT Bell family. As in telephone. As in one of the most important inventions in history.

He rubs his forehead. “My parents did burden me with unfortunate nomenclature.”

“Please.” I let out a laugh. “You used to brag about it all the time.”

“Things change.” His blue eyes widen as if he’s joking, but there’s something flat behind his expression. It’s uncomfortable. Cricket was always proud of his family name. As an inventor, just like his great-great-great-grandfather, it was impossible for him not to be.

Abruptly, he lurches backward into the shadows of his room. “I should catch the train. School tomorrow.”

The action startles me. “Oh.”

And then he bounds forward again, and his face is illuminated by pink and white twinkle lights. His difficult equation face. “See you around?”

What else can I say? I gesture at my window. “I’ll be here.”

chapter five

Max picks his black shirt off his apartment floor and pulls it on. I’m already dressed again. Today I’m a strawberry. A sweet red dress from the fifties, a long necklace of tiny black beads, and a dark green wig cut into a severe Louise Brooks bob. My boyfriend playfully bites my arm, which smells of sweat and berry lotion.

“You okay?” he asks. He doesn’t mean the bite.

I nod. And it was better. “Let’s get burritos. I’m craving guacamole and pintos.” I don’t mention that I also want to leave before his roommate, Amphetamine’s drummer, comes home. Johnny’s a decent guy, but sometimes I feel out of my depth when Max’s friends are around. I like it when it’s just the two of us.

Max grabs his wallet. “You got it, Lo-li-ta,” he sings.

I smack his shoulder, and he gives me his signature, suggestive half grin. He knows I hate that nickname. No one is allowed to call me Lolita, not even my boyfriend, not even in private. I am not some gross old man’s obsession. Max isn’t Humbert Humbert, and I am not his nymphet.

“That’s your last warning,” I say. “And you just bought my burrito.”

“Extra guacamole.” He seals his promise with a deep kiss as my phone rings. Andy.

My face flushes. “Sorry.”

He turns away in frustration but says softly, “Don’t be.”

I tell Andy we’re already at the restaurant, and we’ve just been walking around. I’m pretty sure he buys it. The mood killed, Max and I choose a place only a block away. It has plastic green saguaro lights in the windows and papier-mâché parrots hanging from the ceiling. Max lives in the Mission, the neighborhood beside mine, which has no shortage of amazing Mexican restaurants.

The waiter brings us salty chips and extra-hot salsa, and I tell Max about school, which starts again in three days. I’m so over it. I’m ready for college, ready to begin my career. I want to design costumes for movies and the stage. Someday I’ll walk the red carpets in something never seen before, like Lizzy Gardiner when she accepted her Oscar for The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert in a dress made out of golden credit cards. Only mine will be made out of something new and different.

Like strips of photo-booth pictures or chains of white roses or Mexican lotería cards. Or maybe I’ll wear a great pair of swashbuckling boots and a plumed hat. And I’ll swagger to the stage with a saber on my belt and a heavy pistol in my holster, and I’ll thank my parents for showing me Gone with the Wind when I had the flu in second grade, because it taught me everything I needed to know about hoop skirts.

Mainly, that I needed one. And badly.

Max asks about the Bell family. I flinch. Their name is an electric shock.

“You haven’t mentioned them all week. Have you seen . . . Calliope again?” He pauses on her name. He’s checking for accuracy, but, for one wild moment, I think he knows about Cricket.

Which would be impossible, as I have not yet told him.

“Only through windows.” I trace the cold rim of my mandarin Jarritos soda. “Thank goodness. I’m starting to believe it’ll be possible to live next door and not be forced into actual face-to-face conversation.”

“You can’t avoid your problems forever.” He frowns and tugs on one of his earrings. “No one can.”

I burst into laughter. “Oh, that’s funny coming from someone whose last album had three songs about running away.”

Max gives a small, amused smile back. “I’ve never claimed I’m not a hypocrite.”

I’m not sure why I haven’t told him about Cricket. The timing just hasn’t felt right. I haven’t seen him again, but I’m still a mess of emotions about it. Our meeting wasn’t as bad as it could have been, but it was . . . unsettling. Cricket’s uncharacteristic ease compared to my uncharacteristic unease combined with the knowledge that I’ll be seeing him again. Soon.

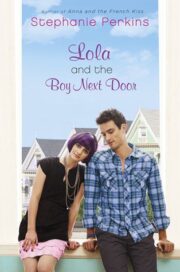

"Lola and the Boy Next Door" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lola and the Boy Next Door". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lola and the Boy Next Door" друзьям в соцсетях.