By then a monument to Jack had been erected in his hometown, Godalming, Surrey. It was designed by the architect Hugh Thackeray Turner, whose son-in-law, George Mallory, had led the early British expeditions to Mount Everest.

The Phillips Memorial Cloister by the River Wey covers three acres of land and is the largest Titanic memorial in the world. It is reverential and serene. It is not known whether or not Roberta Maioni ever visited it.

Roberta was sickly for the rest of her life. She never had children, and in 1950, at the age of fifty-seven, she became bedridden due to extreme arthritis, which, she was convinced, resulted from the long, cold night she spent in Lifeboat No. 8.

In 1961, the White Star Line finally awarded her $280 in compensation for her suffering and losses. “It’s not much use to me now,” she said at the time. She died two years later in an English nursing home. In 1999, the poem that she wrote—along with some of her other Titanic memorabilia—sold at auction for £10,000.

Two days after the Carpathia docked, the Countess of Rothes spoke about the sinking for an article that appeared in the New York Herald. What is known of her feelings about that night comes largely from her extensive remarks at that time. She did not speak publicly about the Titanic again, but in 1956 she agreed to be interviewed by David Astor, the publisher of The Observer and a cousin of Colonel John Jacob Astor, who had died in the disaster and whose young wife had stood near the Countess on the Boat Deck before they boarded the lifeboats. By then the Countess was seventy-seven years old, and had had heart trouble for some time. A week before the scheduled interview, she died peacefully at her home, slipping away in the night.

Her cousin Gladys Cherry died in 1965. She, too, was childless, though she was married for many years to a retired British army officer.

As her life went on, Gladys became increasingly tough-minded about the events of that April night, and years after the sinking, when someone asked her if she had crossed on the Titanic, she gave a wry smile.

“Part way,” she said.

Today, in the perpetual silence of the deep, the place where the Titanic’s grand staircase once stood is a gaping hole useful to submersibles seeking access to the wreck’s interior. On what remains of her deck, hanging over the side, lies a slightly curved iron bar that measures twelve feet long and six inches wide, half of which hangs over the starboard side. It is one of the Titanic’s davits, an eerie, nearly beautiful object that appears to be reaching up, like an arm with a severed hand.

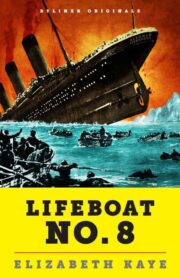

Covered in orange rusticles, it is destined to remain where little abides except iron-eating bacteria, bottom-dwelling rattail fish, and Galathea crabs. As it happens, this is the davit that was used for the first and only time on April 15, 1912, at 1:10 in the morning, when it lowered Lifeboat No. 8 and conveyed its passengers on the journey that, in a certain, essential sense, would never end.

A Note on Sources

All dialogue and thoughts attributed to survivors in Lifeboat No. 8. are reconstructed from first-person accounts and newspaper interviews of survivors, letters written by them, and testimony given by survivors at the American and British inquiries into the sinking of the Titanic.

Selected Bibliography

Archbold, Rick, and Dana McCauley, with a foreword by Walter Lord. Last Dinner on the Titanic (Hyperion, 1997).

Ballard, Dr. Robert D., with an introduction by Walter Lord. The Discovery of the Titanic (Madison Press Books, 1995).

Barratt, Nick. Lost Voices from the Titanic: The Definitive Oral History (Palgrave and MacMillan, 2010).

Beesley, Lawrence. The Loss of the SS Titanic: Its Story and Its Lessons, By One of Its Survivors (Kindle Edition, 2011).

Bryceson, Dave, compiler. The Titanic Disaster: As Reported in the British National Press April–July 1912. (W.W. Norton, 1997).

Butler, Daniel Allen. “UNSINKABLE”: The Full Story (Stackpole Books, 1988).

Davie, Michael. Titanic, the Death and Life of a Legend (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987).

Lord, Walter. A Night to Remember (Henry Holt and Company, 1955).

Lord, Walter. The Night Lives On (William Morrow, 1986).

White, John D.T. The RMS Titanic Miscellany (Irish Academic Press, 2011).

Bigham, Randy Bryan. “A Matter of Course,” Encyclopedia Titanica, 2006.

Maioni, Roberta. “My Maiden Voyage,” The Daily Mail, 1926.

“Statement by Harold Bride,” New York Times, April 19, 1912.“Titanic: The Countess of Rothes and the Phantom Light,” New York Herald, April 21, 1912.

“Titanic’s Loss Adds to Victims Estate,” New York Times, June 22, 1913.

“Woman Survivor of Titanic Tells of the Last Hours of Ship,” Christian Science Monitor, April 19 1912.

Encyclopedia Titanica. www.encyclopedia-titanica.org.

U.S. Congress, Senate, Hearings Before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Commerce United States Senate, Sixty-second Congress, Second Session, pursuant to S. Res. 283, Directing the Committee on Commerce to Investigate the Causes leading to the wreck of the White Star liner “Titanic”… Official Transcript.

Shipping Casualties (Loss of the Steamship Titanic). Report of a Formal Investigation into the circumstances attending the foundering on April 15, 1912, of the British Steamship Titanic of Liverpool, after striking ice in or near Latitude 41° 46' N. Longitude 50° 14' W., North Atlantic. Whereby loss of life ensued (Cd. 6352) (HMSO, 1912).

White Star Line. Record of Bodies and Effects (Passengers and Crew S.S. Titanic) Recovered by Cable Steamer MacKay Bennett. Including Bodies Buried at Sea and Bodies Delivered at Morgue in Halifax, N.S.

About the Author

A longtime contributor to Esquire, Rolling Stone, and The New York Times, Elizabeth Kaye is the author of Mid-Life: Notes from the Halfway Mark and Ain’t No Tomorrow: Kobe, Shaq, and the Making of a Lakers Dynasty, as well as the Byliner Original Sleeping with Famous Men.

"Lifeboat No. 8" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lifeboat No. 8". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lifeboat No. 8" друзьям в соцсетях.