When Jack returned to the wireless shack, he told Harold Bride to put on his life belt. “Things look queer,” he said. “Very queer indeed.”

Then he went back to the wireless set, sending one message after another, even though the power was fading and it was hard to get a spark. In any case, by then he would have known that it was far too late for his efforts to prove anything but futile.

At 2:05 a.m., Captain Smith appeared in the shack again. “Men, you have done your full duty,” he told them. “You can do no more. Abandon your cabin. Now it’s every man for himself.”

If Jack heard the Captain, he gave no sign. His bruised, reddened fingers still tapped out CQD… SOS… CQD…

“You look out for yourselves,” Captain Smith said, more forcefully. “I release you.” Then, as if talking to himself, he added softly, “That’s the way of it at this kind of time.”

But Jack would not stop. “Come quick,” he cabled the Carpathia, “engine room is filling up to the boilers.” He was so engrossed that he did not notice the water seeping across the floor. Nor did he see the stoker who had crept up behind him and was trying to remove the life belt that Harold had fixed in place because Jack had been too absorbed in his task to bother with it. Harold grabbed the stoker. Jack leapt up. The incalculable frustrations of the past few hours were released as they beat the stoker senseless.

By then the wireless had lost all power. Harold Bride ran fore. Jack ran aft. There was no time to say “Godspeed.”

XII

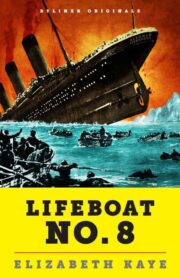

The passengers in Lifeboat No. 8 looked back at the ship, where some fifteen hundred people crowded the stern, clustered as far from the rails as possible. They huddled together, some weeping, some praying, all conjoined in what an onlooker would later describe as “a mass of hopeless, dazed humanity.”

The melodies of the eight-man band drifted across the water. Their songs? Who can say? Some were convinced they heard ragtime, others said the last song was “Autumn.” Still others insisted it was the hymn “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”

The vantage point of Lifeboat No. 8 obscured the particulars of the final, excruciating scene: the English priest making his way through the forsaken crowd, taking confessions, the unwavering Isidor and Ida Straus side by side on the deck, which was now slanting upward, the Allisons standing near them, Mrs. Allison clutching her husband’s hand and sheltering her little daughter in her skirts.

Mere hours had passed since the passengers in Lifeboat No. 8 had nibbled on after-dinner chocolates and petits fours and lain in their Queen Anne and Louis XV beds, soothed by the constant rhythm of the Titanic’s giant engines. Yet now they were afloat in the forbidding sea, staring up at the mightiest ship ever made and keeping their distance from her because she was sinking.

The lights in every window and porthole of the Titanic still gleamed with stubborn brilliance. But these rows upon rows of lights were meant to be parallel with the sea, and now they were positioned at a dreadful angle that grew ever more extreme as 150 feet of the ship’s massive, wounded hulk rose out of the water.

Higher and higher she rose, until the forward funnel came crashing down into the ocean, crushing dozens of men desperate enough to believe they could save themselves by swimming. When the Titanic could rise no more, she paused and hung there, motionless, suspended, as if refusing to succumb to her awful destiny.

On the decks, husbands, wives, sisters, and brothers were rent from one another as entire families tumbled down, down, down into the deadly, frigid sea: steerage passengers from Ireland and Holland, Italy and Armenia, bound for a new life; stewards and engineers, plate washers and firemen proud to be chosen for the great ship’s maiden voyage; Major Archibald Butt, President Taft’s favorite military aide; Clarence Moore, master of hounds of the Chevy Chase Hunt; the ship’s eight noble musicians; Margaret Rice and her five boys; Anna and William Skoog, their two sons and two daughters; and the three wealthiest men on board, who had tried to save others but not themselves, and who were, as Benjamin Guggenheim said, “prepared to go down like gentlemen.”

As they fell, every light on the ship went out, came back on in a single flash, then went out again, extinguished forever. The sudden darkness was followed by an earsplitting, hellish roar as four giant engines fell from their moorings and the glorious etched glass dome of the Grand Staircase shattered and everything loose came crashing down: Louis Vuitton wardrobe trunks; 29,000 pieces of glassware; 44,000 pieces of cutlery; potted palms from the Parisian café; the marmalade machine owned by passenger Edwina Troutt; fifty cases of wine; seventy-five cases of anchovies; three crates of models for the Denver Museum; Mrs. White’s locked suitcases; the Countess of Rothes’s diamond belt buckle; the miniature photograph of Gladys Cherry’s mother; pans of newly baked breakfast rolls; a copy of The Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam, adorned with a thousand precious gems that had sold at auction to an American bidder; the specially commissioned Royal Crown Derby dinner service; William Carter’s new Renault automobile; and four cases of opium.

Then there was quiet once again and the Titanic seemed to settle down, and for one long moment it seemed as if the miraculous might happen and she would right herself. But then she arched up and paused once more before acceding to a swift descent. The most awful part, the Countess thought, is seeing the rows of portholes vanishing one by one.

Seated behind the Countess, Mrs. Margaret Swift looked at the watch she wore on a platinum chain around her neck. It was 2:20 a.m.

XIII

Maria Peñasco screamed for her husband. The Countess handed the tiller to Gladys, then slipped down beside Maria and held her. Poor woman, she thought, her sobs are unspeakable in their sadness.

Then came other screams, the horrifying screams of more than a thousand women and men, struggling and adrift in the subfreezing water, frantically seeking to steady themselves on floating crates, tabletops, deck chairs, or someone else’s back. Their despairing cries carried across the still-calm water: “Save one soul!” … “Help, please, help!” … “Oh my God, oh my God…”

The Countess held Maria tighter as she tried in vain to keep her from hearing those agonized cries.

How long did the pleas and moaning and shouting last? Some said ten minutes, others said an hour. All agreed that they faded slowly, inexorably, as lives ebbed away, one after another. Most of the dead did not drown. They froze to death, their cork-filled life belts keeping them afloat as the sea became studded with corpses that looked like broken dolls. Finally, the last of the cries were replaced by a deathly accusatory silence.

The quiet is more terrible, thought Roberta, than the sounds that went before.

In its wake, the Countess was overwhelmed by a feeling she could identify only as “indescribable loneliness.”

“Let us row back!” Gladys Cherry implored the other passengers in Lifeboat No. 8, “and see if there is not some chance of rescuing anyone who has possibly survived.”

Mrs. Swift agreed. So did the Countess and Able Seaman Jones. But the others were adamant that no good could come from steering a boat that held sixty-five people into a disaster field where hundreds upon hundreds were dead or dying.

“You have no right to risk our lives,” one woman insisted, “on the bare chance of finding anyone alive.”

“The Captain’s own orders were to ‘row for those ship lights over there,’ ” said another. “You have no business interfering with his orders.”

Reluctantly, the four who wished to return to the site of the sinking yielded to the majority, against their will, their faith, and their better judgment. The ghastliness of our feelings, thought the Countess, never can be told.

“Ladies,” said Seaman Jones, “if any of us are saved, remember: I wanted to go back. I would rather drown with them than leave them.”

Then everyone fell silent. Mrs. White looked around at the flat, glassy sea, the star-laden sky. Somehow, it is more dreadful, she thought, for all this to have happened on so beautiful a night.

XIV

The women in Lifeboat No. 8 took up the oars and rowed on, encouraged by the masthead lights of a ship that was now in the near distance, no more, it seemed, than three miles away. The cold made them miserable, for even the heaviest fur coat was little protection, and many of the women were thinly dressed at best. Dr. Leader wore a blue serge suit and a steamer hat, another woman was clad in an evening gown and white satin slippers.

But the light was their hope, their beacon, so they steeled themselves and rowed toward it. With Gladys still at the tiller, the Countess rowed while comforting Maria Peñasco, who sat sobbing beside her, the young bride’s face twisted in such raw anguish that the others could not bear to look at her. Mrs. Bucknell took up an oar, proud to be rowing beside a genuine countess and stopping only when her hands became too blistered to continue.

Margaret Swift, a hardy forty-six-year-old churchgoing lady, took an oar and never put it down. She was placid, as if she had been in a circumstance as dire as this many times before. Watching her, the Countess thought, She is magnificent, not only in her attitude but in the whole way in which she works.

"Lifeboat No. 8" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lifeboat No. 8". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lifeboat No. 8" друзьям в соцсетях.