“Lower away,” said the Captain. “Good-bye,” he said to Seaman Jones. “Remember: you are British.”

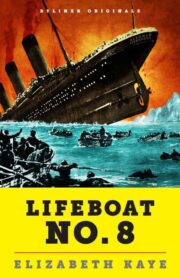

Lifeboat No. 8 swung out from the deck, held sixty feet above the open sea by its iron davit. Tillie Taussig, grasping her husband’s arm, kept watch as the boat was lowered, mere inches at a time, until her daughter disappeared from sight. “Ruth!” she cried out, an exclamation as tortured as it was unintended. Two officers, seeing Mrs. Taussig momentarily distracted, tore her from her husband’s side, lifted her—one by the head and one by the feet—and dropped her over the side of the deck into the lifeboat. She struck the back of her head on one of the wooden seats, but her heavy fur coat saved her from further injury.

Lifeboat No. 8 continued its shaky downward passage, held by ropes as thick as a boxer’s fist, while an officer shouted, “Aft… Stern… Level… Both together…” and the boat tilted at one end, then the other. Mr. Taussig ran to the rail and looked on as Gladys Cherry helped his sobbing wife to a seat.

Caroline Bonnell looked up at the deck and caught Washington Roebling’s eye. “You’ll need a pass,” he called out, “to get back on the ship in the morning!”

Mollie Wick stared bleakly at her husband. She could see him standing at the rail as officers and seamen milled around him. He was a dynamic, powerful man, but now he seemed so forlorn and bereft. He was waving.

As Lifeboat No. 8 descended slowly, painstakingly, to the water, its passengers passed still-gleaming decks where they had lately waltzed and been indulged by cabin stewards and feasted on roast squab with cress and peaches in Chartreuse jelly.

Down they went, away from the ship’s unapologetic splendor: the sumptuous first-class cabins where walls were covered with tapestries and sitting rooms were warmed by coal-burning Adam fireplaces; the à la carte dining room decorated in Louis XIV style, with its candelabra lamps and floor-to-ceiling walnut paneling; the ladies’ writing room, with its velvet-upholstered chairs and handmade Axminster carpets; the reception and smoking rooms, with their Jacobean wall carvings and design references to the palatial manor of Haddon House and Versailles.

The lifeboat dropped lower and lower, passing the Turkish baths, with their Arabian decor; the squash court; the gym with its two electric horses, electric camel, and electric back-rubbing machine; the galley, initially stocked with seventy-five thousand pounds of fresh meat, a thousand sweetbreads, and six thousand pounds of fresh butter; the first-class dining room, with its two thousand egg spoons, one thousand oyster forks, fifteen hundred grape scissors, and five hundred oak chairs embellished with carvings of English roses or French fleurs-de-lis or Scottish thistles; the three first-class elevators installed so passengers—as stated in the flowery sales brochure—“may be spared the labour of mounting or descending stairs.”

The Titanic had been outfitted with anything and everything a first-class passenger could possibly desire, except, of course, for sufficient lifeboats and binoculars to aid the lookouts in the crow’s nest. Not that the binoculars weren’t on board; they were, but none of the officers or seamen had known where to find them. As for the lifeboats, each of the davits was equipped to hold four boats, which would have accommodated more individuals than there were on board. But four boats would have taken up a bit more space on the promenade deck, and, in any case, the davits looked ever so much nicer holding just one.

To Mrs. White it seemed an eternity until Lifeboat No. 8 reached the water, and they heard an officer call from the Titanic’s deck, “Let her go!” For Gladys Cherry, the lowering of the boat into the darkness had been frightful, and as they touched down on the water she thought, We have done a foolish thing to leave that big, safe boat.

As they floated away from the ship, the twenty-seven people aboard Lifeboat No. 8 were unmoving and silent, mired in pain and musings and memories.

Bedroom steward Alfred Crawford had spent thirty-one years on North Atlantic liners—so many years of travel without the slightest glitch. Earlier that evening he had helped an elderly passenger into his life belt, then bent down and tied the man’s shoes. He had not seen the gentleman since, and now he wondered what had become of him.

Mrs. White recalled that, earlier in the day, it had become so chilly in her cabin that she summoned a steward to close the porthole window. “We must be very near icebergs,” she had told Marie Grice Young, “to have such cold weather as this.”

Miss Young thought about John Hutchinson, the ship’s carpenter, who had taken her to the cargo hold each day so she could check on the two dozen live chickens she had purchased in France to provide eggs at Mrs. White’s country home. He had been so kind, and now she remembered what he had said when she tipped him with several gold coins. “It’s such good luck to receive gold on a first voyage.”

In the seat behind Miss Young, Dr. Alice Leader was thinking about one of her traveling companions, Frederick Kenyon. Such a charming man, she reflected, so honorable and good. They had had a lovely conversation just a few hours ago, and now he was still on the ship while Mrs. Kenyon sat beside her in the lifeboat, stunned and weeping. Dr. Leader did not wish to judge, but there was one thing she absolutely knew. Nothing could part me from my husband, she thought, in a time of danger.

The Countess watched the other passengers, concerned about how they would conduct themselves in this small boat on this freezing night. Above all things, she told herself, we must not lose our self-control.

Yet there were signs of trouble. Mrs. White was glaring at the two young stewards, who had taken out their pipes, packed and lit them, and now stood in the lifeboat smoking as leisurely as if they were on the beach at Brighton.

In the back of the boat, several women quarreled about not having enough room to sit down. The Countess calmed them, speaking in a quiet, determined manner. Seaman Jones was at the tiller, listening. This lady, he thought, has a lot to say. Her fine way of talking to the other passengers impressed him.

The two young stewards finally took up oars, but they rowed in such a haphazard manner that the lifeboat was set spinning in a circle.

Mrs. White turned to one of them. “Why don’t you put the oar in the oarlock?” she asked.

“Do you put it in that hole?” asked the steward. “I never had an oar in my hand before.”

“And you?” she asked the other man.

“I never held an oar either,” he said, “but I think I can row.”

Every woman on the lifeboat watched as the two men clumsily handled the oars and made it all too plain that, in order to escape the ship, they had told the Captain they could row when they couldn’t. How can it be, thought Mrs. White, that these are the men we are put to sea with, when all those magnificent fellows left on board would have been such a protection to us?

Able Seaman Jones turned to the stewards. “The captain has told me to row to the lights,” he told them. “We must pull toward them.”

But the stewards set the boat spinning again, and when Jones reprimanded them, their faces flushed with anger. “If you don’t stop talking through that hole in your face,” one of them said, “there will be one less in the boat.”

Seaman Jones glared at the stewards as they set down the oars and retreated to the bow without saying another word. It was clear to the Countess that the seaman would have to row. She turned to him. “Would you care to have me take the tiller?” she asked.

“Certainly, lady,” he said.

With three other men on board, this was an unusual concession: British women were meant to be wives, mothers, and decorative, in that order. They were not permitted to vote unless they were property owners. And yet, thought Seaman Jones of the delicate countess, she is more of a man than any we have on board.

The Countess lifted the hem of her ermine coat and climbed aft. She asked her cousin to take up an oar. As Gladys and Seaman Jones rowed, the Countess deftly steered the boat, a resolute and unlikely vision in her furs and pearls.

Lifeboat No. 8 moved slowly through the still waters. “Don’t row far out,” one woman called. “We ought to stay very near the ship so we can get back on her.”

“No, we must get away,” another insisted.

“I am pulling for the light,” Seaman Jones said firmly. That ended the conversation, but as he rowed, the light seemed to retreat further and further.

Finally he swung his oar back into the boat. He could not reach the light, he reckoned, so it would be best to stand by. He was still convinced that they had been sent away only for an hour or so. Soon, he thought, the crew on deck will get the water pumped out of the ship and she’ll be squared up again.

XI

On the Titanic, Jack Phillips left his post at the wireless and took another walk around. It was 1:50 a.m. With the lifeboats gone and the bow underwater, the scores of people remaining on board seemed strangely calm, either because they still felt hopeful or because they had resigned themselves to the fact that there was no hope at all. As the icy water filled the staircases and lapped across the Promenade Deck, he saw small gatherings of women and men holding hands and praying, as if, knowing they would soon be dead, they had elected to conduct their own requiems.

"Lifeboat No. 8" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lifeboat No. 8". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lifeboat No. 8" друзьям в соцсетях.