On Sunday, April 14, he was besieged, though not because of the six messages from nearby ships warning of an ice field ahead. The trouble came from first-class passengers for whom the wireless was a delightfully new and intriguing toy. They wrote reams of messages to family and friends—mostly along the edifying lines of “How are you? Good voyage”—and Jack had to send them, since they were paying for the service. That April day, there were so many messages that the wireless set broke down.

It took Jack many hours to repair it. At 11 p.m. he was, by his own account, “all done in” and still working his way through his overstuffed inbox. The wireless was a frustrating, unreliable instrument, hobbled by weak signals and inadequate range. It was difficult to get a connection, and that night, just as he finally contacted Cape Race, the liner Californian broke in. “Say old man,” the message read, “We are stopped and surrounded by ice.” It was the seventh ice warning Jack had received that day. Exasperated and exhausted, his reply to the Californian was swift and sharp. “Shut up shut up,” he tapped out. “We are busy.”

Fifty-five minutes later, Captain Edward Smith entered the wireless shack. “We’ve struck an iceberg,” he told Jack. “I’m having an inspection made to see what it has done to us. You better get ready to send a distress call. But don’t send it until I tell you.”

II

Just after midnight, Caroline Bonnell and Natalie Wick, choosing adventure over the warmth of their cabin, put heavy wraps over their nightgowns and went up to the Boat Deck. They were so excited that they failed to notice the piercingly chill air. “Well, thank goodness, Natalie,” said Caroline, “we are going to see our iceberg at last!”

But there wasn’t a berg or an ice floe in sight. Nor was there a trace of wind, though there were more stars in the deep purple, moonless sky than either had ever seen. They stood at the starboard rail, mesmerized by how near those stars appeared to be and by the silvery reflections they cast in the infinite sea that stretched before them, as smooth and unmoving as glass.

The Countess of Rothes and Gladys Cherry entered the A Deck foyer at the foot of the Grand Staircase, where, on the landing, a clock framed by intricate oak carvings of two nymphs was meant to depict “Honour and Glory Crowning Time.”

The staircase, with its majestic balustrades and etched glass dome, was the Titanic’s ultimate signifier; like the ship herself, its very existence embodied man’s ambition, prowess, and progress in the Gilded Age. As word of the iceberg spread, it was the logical gathering place for first-class gentlemen sporting heavy frock coats and woolen mufflers, and ladies in floor-length sable coats hastily donned over satin nightgowns and silk chiffon evening dresses trimmed in gold bullion lace.

Among them were Maria and Victor Peñasco y Castellana, a handsome couple in their early twenties who had recently been married in their native Madrid and were fresh from a Parisian honeymoon. Victor’s mother was convinced the Titanic was doomed and had pleaded with them not to sail on her, but they were so taken with the inherent romance of the ship that they secretly booked passage. Now they stood close together, away from the others, holding hands.

Everyone fell silent when Captain Smith strode through the foyer, accompanied by Thomas Andrews, the ship’s builder. The Captain and Andrews were proud, purposeful men known to be warm and reassuring. They had the explicit trust of their now confused passengers, who scanned their faces for a hint, a clarifying sign. Both men, having made their inspection, knew that the ship was fatally wounded. But their expressions revealed nothing.

Moments later, the Captain reappeared in the wireless shack. “You had better get assistance,” he said.

“Do you want me to use a distress call?” Jack asked.

“Yes, at once,” said the Captain. He handed Jack a piece of paper on which he had scrawled the ship’s position.

Then he hastened to the deck, where he gave his officers the order to uncover the lifeboats and muster the passengers.

III

In the A Deck foyer, the Countess encountered her friend Fletcher Fellows Lambert-Williams, a convivial gentleman who, earlier that evening, had overheard Captain Smith telling several passengers that the ship could be cut crosswise in three places and each piece would float.

“There is nothing to worry about,” he told the Countess. “The watertight compartments must surely hold.”

Just then an officer hurried by. “Will you all get your life belts on!” he called out. “Dress warmly and come up to Boat Deck!”

The Countess looked at Gladys. She did not speak, but she could see that her cousin was as stunned as she was.

The Countess of Rothes had been born into an upper-class life replete with all the grandeur it avails: the privileged girlhood culminating in a union with a dapper earl who presided over a thirty-seven-bedroom family estate centered on ten thousand acres of land, and who lacked for nothing other than the funds she could readily provide; the posh wedding, in the spring of 1900, at which she appeared as a vision in white satin, a crown of orange blossoms and a veil of priceless sixteenth-century Brussels lace; her presentation as a bride at Buckingham Palace, where she caught the ever-traveling eye of the Prince of Wales, who would soon become King Edward VII; the good works as the loyal patron of several charities; and the two beloved sons—the heir and the spare—to carry the line forward.

It was a glamorous and satisfying life. In the Edwardian aristocracy, where marriage and love were often unrelated, the Earl and the Countess were a rarity: a husband and wife so fond of each other that they were derided as “a most unfashionably devoted couple.”

Now the Countess was journeying on the Titanic to join her husband, who planned to purchase and operate an orange grove in California. Five days before, on the morning of the sailing, she had been sought out by a reporter, who asked how she felt about leaving London society for a fruit farm. Now, as she returned to her cabin to don her life belt, the Countess was rueful as she recalled her reply. “I am full of joyful expectation,” she had said.

Jack Phillips sent out the standard call: CQD. It meant “ALL STATIONS ATTEND: DISTRESS.” He followed it with MGY, the call letters of the Titanic.

One ship was no more than twenty miles away. It was the Californian, whose wireless operator, Cyril Evans, had tried to warn the Titanic about icebergs and had been told by Jack to shut up. For Evans, too, it had been a long, tiring day, capped off by Jack’s dismissive reply. At 11:30 p.m. he had turned off the wireless and gone to bed—forty-five minutes before the CQD was sent out.

As the Titanic’s stewards passed along the order to put on life belts, a young seaman stood on the Californian’s deck and detected a curious sight: a giant liner stopped dead in the water. He pointed the ship out to his captain.

“That will be the Titanic,” the captain said, “on her maiden voyage.”

Then he turned away, unperturbed and unhurried, as if what he had seen was not the least bit unusual.

Caroline and Natalie were about to return to their cabin when an officer approached them. “Go below and put on your life belts,” he said. “You may need them later.”

Alarmed and frightened, they rushed down to C Deck to awaken Natalie’s parents, George and Mollie Wick. They relayed the officer’s order, but Mr. Wick chided them. “Why, that’s nonsense, girls. This boat is all right. She just got a glancing blow, I guess.”

Everyone they encountered in the hallway shared his opinion, so the two women returned to their cabin to prepare for bed again. But a moment later an officer knocked at the door and told them to go immediately up to the Boat Deck. “There is no danger,” he said. “It’s just a precautionary measure.”

The first ship to respond to the Titanic’s distress call was a German liner, the Frankfurt. The message she sent back was “OK Stand by.”

The Frankfurt was 150 miles away, but from the strength of her signal, Jack Phillips was convinced that she was the ship closest to them. “Go tell the captain,” he instructed his assistant, a guileless twenty-two-year-old named Harold Bride.

Then Jack hunched over the wireless apparatus and waited anxiously for the Frankfurt’s operator to relay her position. The information didn’t come.

It had been a strange trip for Ella White, a portly, opinionated widow with a vast estate in Briarcliff, New York, and a permanent suite at the Waldorf-Astoria. Boarding the ship, Mrs. White had sprained her ankle. Throughout the voyage she had remained in her cabin, attended by her maid, her manservant, and her companion Marie Grice Young, a cultured thirty-six-year-old given to wearing hats as high as wedding cakes, who had the distinction of having been the music teacher for Theodore Roosevelt’s daughter.

But at quarter past midnight on April 15, remaining in the cabin was no longer an option. Mrs. White put on several layers of warm clothes and insisted that Miss Young do the same. They locked their trunks and bags, and Mrs. White hobbled out of the commodious suite, leaning on a brass-and-wood cane that had a small, battery-operated light mounted on the end of it.

In the coming hours, that cane would be put to use in a way she could never have imagined.

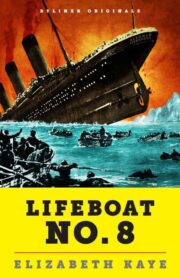

"Lifeboat No. 8" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lifeboat No. 8". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lifeboat No. 8" друзьям в соцсетях.