The evening passed away; if Charles Vernon was morose and silent, that was offset by Mr. Johnson’s uncommon affability. His friendship with Lewis deCourcy was long-standing, but now he took pains to know Sir Reginald better, and in their mutual esteem of Frederica, there was something to promote conversation. He was even cordial toward Eliza and went so far as to throw any praise of the house or the dinner in Mrs. Johnson’s direction.

Sir Reginald’s habits were regular and he kept early hours, and soon after they had taken their coffee and tea, he called for his carriage. Reginald and Vernon departed with him, and Sir James and Mr. Lewis deCourcy left not long after. Frederica waited only for her cousin to be gone before she asked Mr. Johnson if she might trouble him to be conveyed back to Portland Place.

“Indeed, yes, for you will have a great deal to tell Lady Vernon. It will be a great relief—when she is better, I hope that I may be permitted to call upon her—if there was any misunderstanding—any feeling that I did not wish for the acquaintance—you will smooth things over, to be sure.”

Frederica assured him that both her mother and Lady Martin would be happy to know him, and after a round of thanks and promises and engagements that must prolong any parting for an additional fifteen minutes, Frederica departed.

She found her mother so well attended by her aunt, Miss Wilson, and Mrs. Forrester that her presence would have given rise to confusion rather than comfort. As the night progressed into morning, however, all four women had a part to play; and though it was frequently to obey some order of Dr. Driggs’s or to assure each other that Lady Vernon was in no great distress or in any danger, they were diligent, capable, and tireless.

The morning brought the fulfillment of all of Lady Vernon’s hopes and the end of Charles Vernon’s expectations, and though making his arrival well before it had been anticipated, the child gave no indication of being the worse for it. Lady Martin, too overcome with exhaustion and relief, said, “When no ill effects come of it, it is just as well to have a child come early as not,” though she could not help adding that it was the good doctor’s calculations that might have been amiss.

She then declared that he had the Vernon forehead and the Martin chin, while Lady Vernon was content to reassure herself that he had the proper number of limbs and pronounced his name to be James Frederick Vernon.

chapter sixty-one

CHARLES V ERNON WOKE THE NEXT MORNING, LOOKING toward his tenure as master of Churchill Manor with renewed interest. The quarter was due in a matter of weeks, and while it might not be what he would like (as he had done nothing to increase the property’s yield or rents), it would put his creditors off a little longer and help to settle the sort of debts of honor that must be reconciled without delay.

The news of Reginald’s engagement to Frederica was a wretched turn of events, but to see her mistress of Vernon Castle and to have his vague concurrence that he ought to do something for her turned into a fixed sum—eight thousand pounds!—was not to be borne. Still, the sum was not yet surrendered—he must act to repair the damage before it was irrevocable.

Mr. Vernon to Mrs. Vernon

Berkeley Square, London

My dear wife,

I have some very surprising news that I do not doubt will reach your mother by way of Sir Reginald. Your brother has proposed to our niece! After appearances had convinced all of London that she was reconciled to a marriage with her cousin—indeed, she received with him at Cavendish Square and opened the ball in such a manner (so I have heard, as I was not present) as persuaded everyone that the announcement of their engagement was imminent. I begin to wonder if all of the rumors of our niece’s engagement to her cousin were circulated by herself, and if her show of distress while she was with us at Churchill was a charade to pique Reginald’s interest, for you know that a gentleman will always find a woman who is promised to another more appealing than one who is thrown at his head.

This news can please my mother-in-law in only one regard—Reginald does not marry Lady Vernon—and yet, for your sake, I would almost prefer that marriage to this one. Even if Lady Vernon were in health to make the marriage a long one (which I doubt, as reports have her becoming increasingly frail), a wife toward whom his father was so decidedly opposed would always ensure that you remain first with Sir Reginald—now I fear that the distinction of “daughter” is one that you must share with our niece, who, it appears, has now set herself toward securing your father’s affections with the same slyness that allowed her to play upon Reginald’s heart.

I now reside at Berkeley Square with Sir Reginald and have done my part to ensure his comfort, yet one thing is wanting and that is to have you here. You know that your father’s spirits are always at their best and most generous when our children are present, and I fear that if his liberality does not have a proper object, he will be inclined to squander it—and we will be comprehended in his imprudence. Already he has coerced from me a promise that I will provide our niece’s dowry! As this was brought up in company, and before Reginald, I could not protest the injury such a loss would do to our children and was even compelled to agree to a sum—nearly a third of my brother’s legacy! This, when added to some other expenses that my situation must incur (and with no income from the banking house, as that position has been given up), is not insignificant—I can only hope that when the quarter comes due from Churchill Manor, it may be, in some part, offset.

The irony is that our niece has no need for a dowry; not only can marriage to Reginald make it unnecessary, but Sir James Martin has resolved to settle Vernon Castle upon her! To wring an additional eight thousand pounds from me is very unreasonable. Had you been here, I am certain that you might have talked your father out of it—this may yet be possible; your presence and those mild and disinterested arguments that have always prevailed with your father (when added to the company of our dear children) may persuade him to retract this extravagant gesture. If you cannot come at once, an express to your father may do as well, but I think you had better come.

Your devoted husband,

Charles Vernon

Sir Reginald’s letter to his wife was more to the point; they had so little to say to each other that even the most significant communication did not extend beyond a concise disclosure of the facts.

Sir deCourcy to Lady deCourcy

Berkeley Square, London

My dear wife,

You have long looked toward the prospect of Reginald’s marriage and you will be pleased to know that all of the prudent encouragement has not been given in vain. Reginald has made an offer to Miss Vernon and she has accepted him. I have given my consent, and Lady Vernon has likewise given her blessing. I will leave it to Reginald to solicit yours, and will trouble you for a few lines to Miss Vernon and her mother.

Your devoted husband, etc.,

Reginald deCourcy

Charles Vernon had spent so freely that the portion he agreed to settle on his niece represented more than half of what remained of the money bequeathed by his brother. His desire to preserve it long enough for Catherine to come to London and coax her father back into prudence and sense had him fabricating some urgent business at Churchill Manor. He could not meet with Sir Reginald’s agents and attorneys while he was in Sussex, and so immediately after dispatching his letter to Catherine, he made some remarks about a matter of business at the family estate that could not be resolved by correspondence and required his immediate attention. He promised to return in three or four days’ time, which, he calculated, was all that would be allowed for Catherine to receive his letter, apprehend the urgency of their situation, and come to town.

Reginald arrived at Berkeley Square to find Charles gone and his father engaged with his uncle, so he decided to call at Portland Place. His carriage drew up beside Sir James’s and the two gentlemen greeted each other and were admitted together.

Sir James was at once aware of some disruption in the household, for the footman’s livery was half-buttoned and his wig askew, and Miss Wilson appeared from below with a shawl thrown over her nightdress and a tea tray in her hands.

“Miss Wilson!” Sir James cried. “What is the matter?”

She immediately handed her tray to the footman with orders that he take it up and ask Lady Martin to come down, then showed the gentlemen into the drawing room. She bade them sit, in a manner that did credit to her self-command.

“What is the matter?” Sir James demanded once more, with more feeling than civility. “Why is there no fire? Why are the drapes still drawn? Has someone been taken ill?”

Lady Martin bustled into the room, her dress disordered and her hair hastily tucked under a cap. Her face revealed her exhaustion, but her eyes were bright and her expression joyful. “What do you mean by coming upon us so early—it is only eleven o’clock! Why do you not stay in bed until noon anymore? You mean to become steady and sensible just to plague me. If it is your influence, Mr. deCourcy, I cannot protest. Come, sir, and we will have a comfortable chat—for my Frederica has only just got to sleep and I do not think you would have me wake her. As for you, James, you may go to Susan—she is very comfortable now, and when she heard that you had come, she decided that she would as soon see you now as later—but you must not keep her long, for she is very weak and will not stand much conversation.”

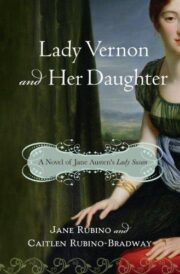

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.