Miss Hamilton and her mother were deeply mortified by Reginald’s marriage, but as the word got round of Vernon Castle’s stateliness and beauty, they made a gesture of rapprochement in order to gain admission to the estate and kept up their friendship with Mrs. Lewis deCourcy so as to widen their acquaintance among the eligible gentlemen at Bath. Yet, despite all of Lady Hamilton’s determination to get them husbands, and her daughters’ thirty thousand apiece, many years were to pass before any offers of consequence came their way.

Lucy Smith and her husband were frequent visitors at Vernon Castle and Bath; they were always cheerful and affectionate, possessing the sort of good-natured exuberance that might settle into contentment or sink into imprudence and misfortune; the latter was to be their fate, but not for many years.

As for Manwaring, he drew a harder lot than mere folly merited, for having pursued every woman but his wife, he now came to think that only Eliza had suited him after all; she had been a capable mistress of Langford and the possessor of a fortune that brought him fifteen hundred pounds per annum without having to do anything much for it. She had no sooner won over Mr. Johnson and installed herself at Edward Street when Manwaring set about courting her, as energetically as he had done before their marriage.

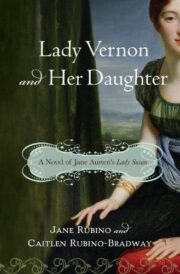

Authors’ Note

Lady Susan was written by Jane Austen in the mid-1790s, when she had a body of lively juvenilia behind her and the first draft of what was to become Sense and Sensibility immediately ahead. The protagonist, Lady Susan (Vernon) “the most dangerous coquette in England,” is a beautiful widow with a daughter of marriageable age who descends upon her brother-in-law’s household after her flirtations have made her unwelcome at the home of her friends the Manwarings. Through a series of letters—principally between Lady Susan and her London friend Alicia Johnson, and Lady Susan’s sister-in-law, Catherine Vernon, and Catherine’s mother, Lady deCourcy—we derive a portrait of a protagonist who is both captivating and calculating, with the combination of a scintillating wit and self-interest that Austen would later employ in the character of Mary Crawford in Mansfield Park.

Unfortunately for fans of her work, Austen’s Lady Susan is too short, characterized by a style that was a decade out of date when Austen recopied it in 1805. Perhaps, at age thirty, she felt the affection to preserve it, but was too conscious of its shortcomings or too preoccupied with developing her other work to revise it.

When we decided to develop a full-length novel from Lady Susan, we started at the end, where Lady Susan and her daughter are suitably married, and then studied both the narrative and Austen’s other works, to extract the motives and mechanism for bringing these unions about. Certainly Lady Susan is strong-willed, reckless, even malicious, but these do not disqualify her as an Austen heroine. Elizabeth Bennet and even Fanny Price are strong-willed; Marianne Dashwood is reckless, almost to a fatal degree; and it is hard to find anything in Austen’s canon more malicious than Emma’s retort to poor Miss Bates. Lady Susan’s character, therefore, was not exempt from moderation, so long as she might be framed in terms of a justifiable object—marriage.

It was not a stretch to attribute a practical incentive to Lady Susan’s coquetry: it is a truth, acknowledged throughout Austen’s canon, that an unmarried woman, in possession of neither property nor fortune, must be in want of a husband for herself and/or her daughters. “Charming” is not what Lady Susan is but what she does, in order to secure husbands for herself and Frederica Vernon. When she concedes, in letter 2, that she lured Sir James Martin away from Miss Manwaring, she adds, “It was the advantage of my daughter that led me on…. Sir James did make proposals to me for Frederica,” and when Frederica resists the union, Lady Susan laments that “I have more than once repented that I did not marry him myself.” When Lady Susan is introduced to the wealthy Reginald deCourcy, Mrs. Johnson, in letter 9, advises her “by all means to marry him,” and Lady Susan’s response asserts, “It is true that I am vain enough to believe it [marriage to Reginald] within my reach.” Though Lady Susan says that she “cannot easily resolve on anything so serious as marriage,” Lady Susan’s slender plot, as are the plots of Austen’s mature novels, is advanced by the courtship-obstacles-marriage.

In letter 12, Sir Reginald deCourcy writes to his son, “In the very important concern of marriage especially, there is everything at stake; your own happiness, that of your parents, and the credit of your name.” This is not very different from Mr. Collins when he enumerates his reasons for marrying in Pride and Prejudice; his happiness, that of his patron, and the respectable example he means to set among his parish are foremost. Women without independent means are compelled to be more down-to-earth: Charlotte Lucas’s rationale for accepting Mr. Collins is that “[marriage] was the only honourable provision for well-educated young women of small fortune, and however uncertain of giving happiness, must be their pleasantest preservative from want.”

However expediently her subordinate characters marry, for Austen’s heroines, happy marriage = advantage + affection; otherwise, Elizabeth Bennet’s refusal of one who was the heir to the Bennet estate, and another who came with ten thousand a year would have been inexcusable, and instead of being elevated to the status of heroines, Lady Susan and her daughter would have been demoted to the level of a Charlotte Lucas or a Maria Rushworth, who put security over affection, or a Lydia Bennet, who did the opposite.

The necessity for most women to marry, and to marry well, will help to answer the question, which will be asked, “Why the change from Lady Susan to Lady Vernon?” There are two “Lady Christian Names” mentioned in Austen: the late Lady Anne Darcy and the living Lady Catherine deBourgh, who are sisters and the daughters of an earl, the former married to Mr. Darcy and the latter the widow of Sir Lewis deBourgh. Yet, there is no suggestion, other than the “Lady Susan,” that the protagonist is the daughter of high rank. Had that been the case, she would certainly have commanded more deference, even if she did not deserve it—as is the case with Lady Catherine—and as the daughter of aristocracy, she would likely have had a settlement that would have left her so financially secure that she would not have to contemplate marriage. The possibility of remarriage does not preoccupy Austen’s rich widows—Lady Catherine, Lady Russell, Mrs. Jennings—nor are they concerned with what things cost or how and where they will live.

Lady Susan does have to think about a “preservative from want.” The declaration, in letter 5, that she and her husband had been “obliged to sell” a family property, Vernon Castle, and Sir Reginald’s statement in letter 12 “[Lady Susan] is poor, and may naturally seek an alliance which may be advantageous to herself” suggest it, as does Lady Susan’s lament (letter 2) that the cost of Frederica’s schooling is “immense, and much beyond what I can ever attempt to pay.” It is not until Lady Susan is comfortably established in the home of her in-laws that she can say, “I am not at present in want of money.” In fact, though she is elegant, witty, and beautiful, her situation is not much different from that of the widowed Mrs. Norris in Mansfield Park, resolutely sponging off her richer relations “till I have something better in view” (letter 2).

Could she be the widow of an aristocrat? Even if “Lady Susan” were the proper form of address, the fact that her late husband’s brother is “Mr. Vernon” indicates that no title passed from Sir Frederick to his survivor—he is not Sir Charles, which suggested that Lady Susan is a “Lady” because her husband was a knight—and in that case, she would have been addressed as Lady Vernon. Because part I of Lady Vernon and Her Daughter takes place before the first letter of Austen’s novel, we were able to develop a history of the character that supports this, and while it did result in the sacrifice in the title, we are reminded that it was not Austen’s title, but simply a provisional one attached to the work much later.

The excerpt that follows is the first quarter of Lady Susan. Though underdeveloped and limited by its epistolary form, Lady Susan identifies that point where Austen transformed from hobbyist to novelist.

An excerpt from Jane Austen's Lady Susan

Letter 1

Lady Susan Vernon to Mr Vernon

Langford, December

My dear brother,

I can no longer refuse myself the pleasure of profiting by your kind invitation when we last parted, of spending some weeks with you at Churchill, and therefore if quite convenient to you and Mrs Vernon to receive me at present, I shall hope within a few days to be introduced to a sister whom I have so long desired to be acquainted with. My kind friends here are most affectionately urgent with me to prolong my stay, but their hospitable and cheerful dispositions lead them too much into society for my present situation and state of mind; and I impatiently look forward to the hour when I shall be admitted into your delightful retirement. I long to be made known to your dear little children, in whose hearts I shall be very eager to secure an interest. I shall soon have occasion for all my fortitude, as I am on the point of separation from my own daughter. The long illness of her dear father prevented my paying her that attention which duty and affection equally dictated, and I have but too much reason to fear that the governess to whose care I consigned her, was unequal to the charge. I have therefore resolved on placing her at one of the best private schools in town, where I shall have an opportunity of leaving her myself, in my way to you. I am determined you see, not to be denied admittance at Churchill. It would indeed give me most painful sensations to know that it were not in your power to receive me.

"Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Lady Vernon and Her Daughter: A Novel of Jane Austen’s Lady Susan" друзьям в соцсетях.