She went on for some time to speak of God's omnipotence and the efficacy of the saints, giving arguments and reassurance that sounded hollow to her own ears, and saw with dismay that the shut-in look of before her illness had come back to Blanchette's face. But at last the girl spoke gently. "Ay, Mama, I know." She sighed and pulled herself to the far side of the bed. "I'm so tired - I cannot listen anymore."

CHAPTER XXIV

The next day, Monday, June 10, Katherine and Blanchette moved over to the Privy Suite. Blanchette had never before been in the ducal apartments, and despite her scruples the girl could not withhold wondering admiration when Katherine helped her to walk into the Avalon Chamber. It had been a lovely tower-room to start with, but each year the Duke improved it, spending lavish sums on its enhancement. The mantel of rose Carrara marble, brought by galley from Genoa, had been placed last month, and a master mason had taken two years to carve it with a frieze of falcons, roses, castles and ostrich feathers to embrace all the Duke's emblems.

The window on the Thames had been enlarged, and deepened to an oriel. Along the top half of its three lights ran exquisite tinted scenes of the life of St. Ursula with her eleven thousand virgins, though, below, the panes had been left clear to show the river view. The prie-dieu in a corner niche was of ivory and gold, cushioned with white satin, and it had come from Castile. The red velvet bed was unchanged except that its curtains and tester had been freshened with new embroidery: the Duke had ordered that a sprinkling of her tiny gold Catherine wheels be cunningly inserted amongst the seed pearl foliage, and this had pleased Katherine mightily.

And still beside the bed hung the great Avalon tapestry, with the dark mysterious greens of the enchanted forest and the luminous figures of Arthur, Guenevere and the wizard Merlin.

Katherine never saw the tapestry without remembering what John had said of Merlin's castle when she first came to this room twelve years ago, "It reminds me of one I saw in Castile."

Little had she known then of how much that meant to him.

In seeking to divert Blanchette, Katherine told her a little about the tapestry, but the girl was not much interested, she preferred to sit in the window and watch the river flow by, and as Katherine had hoped, she was delighted with the finger-high ivory figurines of the saints. St. Agnes with her lamb, St. Cecilia with her dulcimer, St. Bartholomew with his flayed skin draped gracefully over his arm - all were carved with an amusing fidelity to life and were, like the little faces on the corbels of churches, obviously portraits of people that the artist had known. The figure of St. Apollonia, holding pincers and a large tooth as symbols of her martyrdom, was so realistic in its swollen jaw and twisted mouth that Blanchette laughed outright.

"Ah, poppet," said Katherine smiling, "you'd not laugh if you'd ever had toothache; it seems 'tis no laughing matter."

"Have you, Mama?" said the girl, putting down Apollonia.

"Nay, I've been lucky, I've all my teeth yet. Though the Duke - -" She hesitated. But with Blanchette now, God be thanked, one no longer had to tread gingerly and avoid mention of everything that had once disturbed her. "The Duke has suffered cruelly with toothache at times, and Hawise, too - as you know."

"Poor souls," said Blanchette absently. She had picked up the figure of the North Country saint, Columba, who held a dove. She touched the dove's tiny head and looked up at her mother. "What happened to my green linnet?"

"It's well, I've fed it myself. We'll send for it so you can hang it in your room."

The girl's grey eyes grew thoughtful, and she said, "I left the cage door open, didn't I - the day I sickened? Didn't it fly away?"

"No," Katherine smiled. "But I've shut the door now. So you may free the bird yourself, as you love to do."

"Perhaps it's happy in its cage, after all," said Blanchette slowly. She looked out of the window towards the line of trees across the river where the rooks were circling. "Perhaps it would be frightened out there."

"It might be," said Katherine. Her heart swelled with gladness. Blanchette was better in every way, not only recovering from the illness, but from all the strange dark rebellions that had preceded it for so long. At last, the girl gave voice to some of her thoughts, and the stammer in her speech had almost disappeared. Soon, Katherine decided she might speak frankly about Robin Beyvill and Sir Ralph, find out what the girl really felt, and help her to understand herself.

Blanchette's pale face flushed suddenly, she looked down at the window-seat and busied herself with standing the saints carefully in a row while she said, "You've been good to me, dearest Mama."

Katherine caught her breath while her arms ached to hug and shelter, but she knew that she must not force this new delicate balance. She contented herself with a quick kiss. "And why not, mouse?" she said lightly.

Tuesday and Wednesday they had a. happy time together. With windows wide open to the soft June air they passed the hours in songs and games. Blanchette played her lute, and Katherine a gittern. Katherine taught her the gay old tune, "He dame de Vaillance!" and they sang it in rondo. They played at Merelles and at "Tables," the backgammoning game, with silver counters on a mother-of-pearl board. They asked each other riddles and tried to invent new ones. Katherine, in persuading her child to light-heartedness, found gaiety herself, dimmed only by a secret worry over Blanchette's hearing.

Piers brought them up delicious food, Mab waited on them methodically, the chamberlain reported that all was running smoothly with the servants, and they saw nobody else. Each found rich reward in this companionship and forgot the painful disagreements that had chafed them before.

Blanchette visibly gained much strength. She could walk about their chambers without help, she was eating well, and some colour had returned to her thin cheeks. Next week they could certainly leave for Kenilworth, Katherine thought joyously - and not very long after that she might begin to look for John's return.

On Wednesday evening the courtyard clock beat out seven strokes as they finished their supper in the Avalon Chamber. Blanchette munched on marchpane doucettes, especially made for her by the head pastry-cook, while Katherine sipped the last drops of the rich amber wine that remained in her hanap. These goblets that they were using were their own, and exceedingly beautiful.

Blanchette's hanap of silver gilt with her cipher was the one given her so long ago as a christening present by the Duke, and Katherine's was a recent New Year's gift from him, a hollow crystal banded with purest gold. This hanap was called Joli-coeur, because a garnet heart was inlaid in its gold cover, and Katherine thought that the goblet always gave to its contents a savour as delicate as its name.

"Brother William hasn't been here since Sunday," said Katherine idly. "Maybe he'll come tonight - though you scarcely need his skill any more, God be thanked."

"I hope he does," said Blanchette reaching for another doucette. "I like him. He looks ugly and grim, yet his hands're gentle. He was like a kind father while I was ill. 'Tis pity he mayn't have children of his own, isn't it?"

Katherine assented, faintly amused at the thought of the friar in a fatherly role. Certain it was that Brother William never had been a secret father, whatever irregular paternity might be indulged in by the rest of the clergy. "He's an exceeding righteous man," she said with some dryness. There was a knock on the door, and she called "Enter!" thinking that it might be the friar come now.

It was a page who announced that there was a tradesman below in the antechamber who wished to see Lady Swynford. A Guy le Pessoner.

"Master Guy!" exclaimed. Katherine. "Show him up, to be sure," and to Blanchette said, " 'Tis Hawise's father."

The fishmonger came in puffing and mopped his glistening moon face on his brown wool sleeve. He bowed to Katherine, glanced at Blanchette and wheezed, "Whew! 'Tis warm for one o' my port to be a-hurrying."

Katherine smiled and indicated a chair. "A pleasure to see you,"

Master Guy's great belly gradually ceased to heave. He put his thick red hands on his knees. "Where's Hawise, m'lady?" he said abruptly.

"At Kenilworth with my little Beauforts. She left a month ago when the Duke went north."

"Ah!" said the fishmonger. " 'Twas what I be telling Emma, but she made me come anyhow."

"Why?" asked Katherine. "Is anything wrong?"

"Nay - not what ye might call wrong" he shrugged. " 'Tis more that me dame's a dithering old 'oman." Master Guy stuck his thumbs in the armholes of his jerkin and frowned.

These last two days there was no doubt that the rebellion had become more serious. The Kentish mob had advanced as close as Blackheath across the river, while Essex men neared

London from the north. Dame Emma had kept badgering him to go and make sure that Hawise was out of possible danger. She had heard a rumour that Lady Swynford remained at the Savoy, though the Duke had left.

"What does Dame Emma dither about then?" asked Katherine anxiously.

"She thinks if them ribauds over on Blackheath should cross the river into Lunnon, there maught be a bad time. I tell her 'tis folly. The King'll calm 'em down. All they want is to set their grievances afore the King. Besides they can't get into town. The drawbridge's up, and the gates all closed." He paused. True, the gates were closed and the drawbridge up now, but there were aldermen who sympathised with the rebels. John Horn. And Walter Sibley, a fellow fishmonger who was responsible for holding London bridge. You couldn't trust either of 'em far as you'd throw a cat.

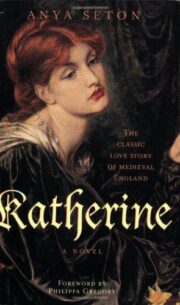

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.