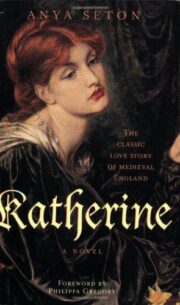

Katherine

Seton, Anya

Hodder (2006)

Tags: Historical, Fiction

SUMMARY:

This classic romance novel tells the true story of the love affair that changed history that of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the ancestors of most of the British royal family. Set in the vibrant 14th century of Chaucer and the Black Death, the story features knights fighting in battle, serfs struggling in poverty, and the magnificent Plantagenets Edward III, the Black Prince, and Richard II who ruled despotically over a court rotten with intrigue. Within this era of danger and romance, John of Gaunt, the king's son, falls passionately in love with the already married Katherine. Their well-documented affair and love persist through decades of war, adultery, murder, loneliness, and redemption. This epic novel of conflict, cruelty, and untamable love has become a classic since its first publication in 1954.

Katherine Anya Seton Hodder (2006) Rating: **** Tags: Historical, Fiction

SUMMARY:

This classic romance novel tells the true story of the love affair that changed history that of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, the ancestors of most of the British royal family. Set in the vibrant 14th century of Chaucer and the Black Death, the story features knights fighting in battle, serfs struggling in poverty, and the magnificent Plantagenets Edward III, the Black Prince, and Richard II who ruled despotically over a court rotten with intrigue. Within this era of danger and romance, John of Gaunt, the king's son, falls passionately in love with the already married Katherine. Their well-documented affair and love persist through decades of war, adultery, murder, loneliness, and redemption. This epic novel of conflict, cruelty, and untamable love has become a classic since its first publication in 1954.

Katherine

ANYA SETON

Copyright (c) 1954 by Anya Seton

About the author

Anya Seton was born in New York City and grew up on her father's large estate in Cos Cob and Greenwich, Connecticut, where visiting Native Americans taught her traditional dancing and woodcraft. One Sioux chief called her Anutika, which means 'cloud grey eyes', a name which the family shortened to Anya. She was educated by governesses, and then travelled abroad, first to England, then to France where she hoped to become a doctor. She studied for a while at the Hotel Dieu hospital in Paris before marrying at eighteen and having three children. She began writing in 1938 with a short story sold to a newspaper syndicate and the first of her ten novels, My Theodosia, was published in 1941. Her other novels include Green Darkness, The Winthrop Woman

Exalted be thou, and thy name

Goddess of Renown or Fame!

"Madame" said they "We be

Folk that here beseechen thee

That thou grant us now good fame . . ."

"I warn you it" quoth she anon

"Ye get of me good fame none

By God! And therefore go your way."

"Alas" quoth they, "And weylaway . . .

Tell us what your cause may be?"

"For me list it not," quoth she.

House of Fame,

by Geoffrey Chaucer

AUTHOR'S NOTE

In telling this story of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, the great Duke of Lancaster, it has throughout been my anxious endeavour to use nothing but historical fact when these facts are known - and a great deal is known about the fourteenth century in England.

I have based my story on actual history and tried never to distort time, or place, or character to suit my convenience.

For those who are interested in sources, I append my main ones below; while for those who may wish to know something of the book's background and the writing of it, here are some brief notes.

My interest in Katherine began one day nearly four years ago when I read mention of her in Marchette Chute's charming biography, Geoffrey Chaucer of England. I subsequently came to know Miss Chute and am extremely grateful for her encouragement.

I then began my research on the fourteenth century, preparatory to the necessary trip to England for more intensive delving and a view of the places associated with Katherine.

Four years of my life have been spent in England, my father was English born, and I have always loved the country dearly, but this special research trip in 1952 was particularly delightful, for it combined the beauties of an English spring with the zest of a treasure hunt.

I visited each of the counties; I studied the remains of John of Gaunt's numerous castles, and searched ever - in the British Museum, in town libraries and archives, in rectory studies, in local legend - for more data on Katherine's life.

Of her little was known, except when her life touched the Duke's and there are few details of that. The Dictionary of National Biography sketch is inadequate, the contemporary chroniclers were mostly hostile (except Froissart), and in the great historians Katherine apparently excited scant interest, perhaps because they gave little space to the women of the period anyway.

And yet Katherine was important to English history.

When, on the English tour, I visited Lincolnshire, I was rewarded with new light. And here I must express my fervent thanks to J. W. F. Hill, Esq., for his cordial help and for his scholarly, comprehensive book, Medieval Lincoln.

I wish also to thank all the kind people in Lincoln who interested themselves in my project, and especially the owners, and the former occupants, of Kettlethorpe Hall Air Vice-Marshal and Mrs. McKee, where I spent charmed days in Katherine's own home, trying to reconstruct the past. Though but a portion of the gatehouse and cellars remains from Katherine's time, the rectory contained one of those invaluable local brochures that are compiled by learned clerical gentlemen. The Manor and Rectory of Kettlethorpe, by R. E. G. Cole, M. A., Prebendary of Lincoln, had a wealth of new information on the early Swynfords, on Hugh and Katherine; and dates - such as the one I have used for Hugh's death - which differ from the accepted ones, but seem incontrovertibly documented. This date suggested the explanation I have used for Hugh's mysterious end.

The names of the major characters in this book will be familiar to students of English history, but I have also tried whenever possible to use actual people for the minor ones; and here John of Gaunt's own registers were invaluable.

For instance, Brother William Appleton, the Grey Friar's, official capacity and eventual fate were as I have shown them. Hawise Maudelyn was Katherine's waiting woman, Arnold was the Duke's falconer, Walter Dysse his confessor and Isolda Neumann his nurse. I have given him no retainers, officers or vassals who are not listed in the "Registers".

To the development and motivations of the story, it has sometimes of course been necessary to bring my own interpretations, but I trust they are legitimate, and backed by probability.

John of Gaunt has been much vilified by historians who have too slavishly followed the hostile chronicles, particularly the Monk of St. Albans' consistently spiteful Chronicon Angliae.

I have naturally preferred the view of his character which was held by his great biographer, Sydney Armitage-Smith, and certainly an impartial look at the facts seems to warrant it.

My "psychological" treatment of the changeling slander arose from several clues. Most of the historians have been puzzled by the Duke's actions at the "Good Parliament" and sudden reversal thereafter; one source ties this in with the probable deep unconscious effect on the Duke of that type of slander, and it seemed to me logical.

In covering a field so vast as the history and politics of this period, I have had to confine myself to those events which would have affected Katherine, but in showing these national events I have tried to extract the truth from the welter of conflicting data and points of view. For the actual accounts of the Good Parliament and the Peasants' Revolt, I have read all the authorities, but have leaned chiefly on the Anonimalle Chronicle of St. Mary's Abbey, York, which gives information not available to the earlier historians.

The existence of Blanchette has been entirely overlooked, but it is documented by Armitage-Smith and also by the "Registers".

These registers have also, by inference, provided me with much of the story, since many entries bear on the personal life of Katherine and the Duke, such as their parting in 1381, attested by a Latin Quit Claim - as well as by those assiduous monkish chroniclers who never lost a chance to attack the Duke - for reasons I have tried to show.

My Latin was not adequate for all this research and various amiable people have helped me, but with Middle French and Middle English I have perforce become familiar and one of the great personal pleasures in writing this book has been the reading of much medieval literature - and Chaucer. It has occurred to me, and here I know I am treading on dangerous ground, that Chaucer may have had his beautiful sister-in-law in mind in occasional passages, particularly in the Troilus and Criseyde.

That I have not invented Katherine's beauty for fictional purposes is borne out I think by the references. John of Gaunt's (now destroyed) epitaph in St. Paul's referred to her as "eximia pulchritudine feminam," an unusual tribute on a tombstone, while the disapproving monk of St. Mary's Abbey called her "une deblesse et enchanteresse"

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.