Blanchette had spoken of her father while the fever clouded her wits. It seemed that she relived the moment when she had bade him good-bye at Kettlethorpe, repeating as Hugh must have said it to her, "Be a good little maid till I return and I'll bring you back a gift from France." It had sent tears to Katherine's eyes to listen to Blanchette's high excited voice as she quoted her father, and had made her think more gently of Hugh then she ever had. It was true that he had shown a shamefaced warmth for his little daughter, though Katherine had scarcely noticed it at the time, so eaten up with miserable love had she been for John.

She summoned Mab to help her to get Blanchette back to bed, and while she washed the girl with cool rose-water she thought with joy of the letter she had received yesterday. It had been sent from Knaresborough last week. John said that he was leaving at once for the Border, that Hawise and the babies had been duly dropped off at Kenilworth and were well. He missed her and expected to be back with her in a month or so. She carried the letter in her bodice next to her heart.

In thinking of it and in singing to Blanchette, who quickly fell asleep, she forgot for some time the extraordinary dilatoriness of the varlet she had sent for food, until hunger reminded her and brought sharp annoyance.

Katherine jangled the bell and after a while a sleepy little page appeared. "Fetch me the chamberlain at once!" she commanded. The boy bowed and scurried off. He returned in a few minutes not with the chamberlain but with Roger Leach, the sergeant-at-arms.

Katherine raised her eyebrows and the big soldier explained. "Chamberlain's gone to Outer Ward, m'lady. He'll come to ye directly, but there's a party o' roving gleemen come into the castle for night's lodging."

"Since when does the chamberlain concern himself personally with the vagabonds who take shelter here and give them precedence over my summons?"

The sergeant looked uncomfortable. He pushed back his helm and scratched his head where the leather caused it to sweat. "Well, 'tis this m'lady, chamberlain thought he best hear what's going on. Some o' the varlets packed theirsel's round the gleemen, seeming so 'tranced wi' their songs, no work's being done."

"No work's being done anyway," said Katherine. "I ordered wine and meat two hours back, nor has it come yet. Have the varlets turned unruly, sergeant?"

"Nay, nay, m'lady!" Leach was shocked and his pride hurt. Though he was directly responsible only for the men-at-arms left at the Savoy, a dozen or so at present, he also aided the old chamberlain and the butler and the master cook in keeping a disciplinary eye on the servants. " 'Tis but midsummer giddiness 'mongst the young folk. A few switchings'll straighten 'em out."

Katherine looked at him thoughtfully. "I think I'll go down and listen to these gleemen's songs."

"Then I'll go wi' ye, m'lady," said the sergeant, adjusting his helm and squaring his shoulders under his padded leather hauberk. "These gleemen shouldn' been let in, 'twas that niddering gate-ward done it."

From this Katherine gathered that the sergeant was a trifle uneasy despite his denial. Travellers of all sorts, from beggars to bishops, frequently came to request a night's lodging and the gate-ward could hardly be blamed for admitting a troupe of gleemen.

She left Mab in charge of Blanchette and walked downstairs to the Outer Ward, where some thirty of the servants were gathered in the angle between the chapel and the stables. They were very quiet, listening intently to five gleemen with harps and bagpipes who were grouped around a well and singing. One of the men stood on the well kerb and seemed to be the leader. Katherine stared at him searchingly, half expecting that it might be the rebel preacher John Ball; but it most certainly was not. This was a pretty lad in a loose blue and scarlet minstrel's jerkin, and the song he sang had nothing to do with Adam and Eve. It sounded rather like a nursery rhyme.

The gleemen sang in a clear flutelike voice and his fellows hummed the melody, which was plaintive and charming:

Jack Milner asketh help to turn his mill aright.

For he hath grounden small, small, small,

The King's son of heaven he payeth for all.

With might and with right, with skill and with will

Right before might, then turns our mill aright

But if might goes before right then is the mill misadight.

" 'Tis gibberish," said the sergeant contemptuously. "No sense to ut."

As he spoke the intent crowd became aware of Katherine. There was a murmuring as heads were turned. She saw Piers, her usual servitor, the scab-headed Perkin and others. They looked at her from the corners of their eyes, and one by one began to melt away towards the kitchens and the stables.

The young glee leader on the well kerb made Katherine a little bow, and called out in a pleasant voice, "Shall we sing for you, fair lady? We know many a dainty love tune. Or shall we juggle for you? By the rood, there's no gleemen in England can do more jolly tricks than we."

"Nay, not tonight, I thank you," she answered. He was a comely youth, and she could not believe that his miller's song had any sinister meaning. Minstrels sang on many topics, and if that jingle had some political reference that escaped her, still a song could do no harm.

She found that the chamberlain agreed with her. He had been listening too from the shadow of the bargehouse and he hastened to join Katherine and the sergeant.

She spoke sternly to the chamberlain about the neglectful servants, and he stammered and begged her forgiveness while tugging unhappily at his sparse grey beard.

Katherine returned to Blanchette and at once Piers came to the chamber with her belated supper. He apologised for his attack of colic and for the stupidity of Perkin, who had come in his stead. He waited on her with his usual smooth efficiency, and Katherine felt that she had been unduly nervous. She did however summon the sergeant once more.

"Can you find out about those gleemen?" she said to him.

"I have, m'lady," answered the sergeant complacently. He had shared a mazer of ale with the young leader and found him a courteous merry-hearted youth who was even now entertaining the varlets' hall with a series of good old-fashioned bawdy songs that everyone knew, and could understand.

"They be good lads," said the sergeant with confidence. "No harm in 'em at all. They've come from Canterbury, where they played for the Princess Joan who was on pilgrimage, and they're bound for Norfolk to play at some lord's bridal feast."

"Yet I hear there's rioting in Kent, sergeant," said Katherine, uncertainly.

"Ay, m'lady, so I've heard too," he said soothingly. "But what o' that? There's no danger here at the Savoy wi' me an' me men to guard it. Them churls down Kent way'll never come to Lunnon, an' if they did they'd not come here - why should they?"

"Very well," she said with a smile. "I know I couldn't ask for a better protector. His Grace has often told me of your courage."

The sergeant flushed with gratification. A simple man was the sergeant, and passionately loyal to the Duke, under whom he had served in battles as far back as Najera. He thrust out his chest and said beaming, "Thanks, m'lady. And how's the little maid now?" He glanced at the bed where Blanchette was sleeping.

"Much better. We'll leave here for Kenilworth next week, I hope."

"Ay - ye'll be longing to see your other little ones. 'Tis a good mother ye are, m'lady, I was saying that to me old wife only yestere'en - -" The sergeant gulped and stopped, remembering his wife's pithy retort which had to do with the highly irregular status of Lady Swynford's motherhood. "I'll be off to me duties, if you please."

Katherine sat on for a few minutes in the window-seat. The chamber was cool and dark, the long June twilight had at last faded and only the watch candle burned in its silver sconce by the bed.

Blanchette stirred and murmured something, her fingers plucked restlessly at the sheet. Katherine lay down beside her and the girl sighed and grew quiet. Katherine drew her against her breast, Blanchette nestled as she had used to do long ago, the whole of her slight body lax and trusting in her mother's arms. A warm blissful tenderness flowed over Katherine and she rested her cheek softly against the clustering curls.

Suddenly Blanchette started and giving a moan, sat up and opened her eyes.

"What is it, darling?" Katherine cried. The girl's eyes were dazed, and Katherine repeated her question. Since the bursting of her eardrums, Blanchette did not hear keenly.

Blanchette licked her pale fever-chapped lips, and gave a frightened little laugh. "Dream," she said, "horrible dream - -I was drowning and you - -" She stared at her mother's anxious face and stiffened, drawing away. "By Sainte Marie, how silly to be frightened by a dream," Blanchette said in a strange tight voice. She crossed herself, then as though the familiar protective gesture had suddenly developed meaning, she said, "Mother, do you ever pray anymore?"

"Why, darling, of course I do," said Katherine much startled. "I've prayed for your recovery, I went to Mass this morning - -"

"But not the way you used to. I remember when I was little, at Kettlethorpe - it was different. And you're right: prayers do no good. I don't believe Christ or His Mother or the saints care what happens to us - if indeed any of them really exists."

"Blanchette!" cried Katherine, much shocked to have the child voice the wicked doubts that she had felt herself. "These are sick fancies - -"

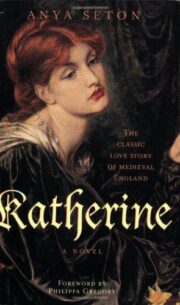

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.