The King was alone with Alice Perrers when he was stricken with an apoplexy. She had been sitting on his bed, casting dice with him, and provoking him to delighted titters by the outrageous stakes she demanded - the Archbishop of Canterbury's mitre, the province of Gascony, the crown regalia - when the King gave a loud cry and began to gobble in his throat. His staring eyes swam with red, one lip drew up in a snarl, as half of his face was turned to stone.

Alice screamed and jumped off the bed. The King fell back on the pillows. He gave forth great snoring gasps as she watched him, horrified. She saw that he must die and that her long power was at an end. She bent quickly and pulled three richly jewelled rings from off his flaccid fingers.

She thrust the rings in her bodice and backed away trembling, then she turned and fled from the chamber, pausing only to shout at a page that he must get a priest. She ran from the palace to the river, had herself ferried over, and by bribing an innkeeper on the western bank secured a horse and set out for safety to a nook in Bedfordshire where a certain knight owed her return for many favours.

The old King died soon and alone, except for a friar that the frightened page had found. His sons and little Richard, who was now the King of England, did not reach Sheen for some hours.

England mourned courteously for the King, the people wore sad clothes, black cloth shrouded their windows, and Requiem Masses were said throughout the land. Edward's funeral procession and burial next to Queen Philippa on the Confessor's mound in Westminster Abbey were conducted with doleful pomp. The dirge-ale was drunk to the accompaniment of decorous sighs. But everywhere eyes turned with hope and rejoicing to the fair charming boy who would be crowned on the sixteenth of July.

Angers faded. The bishops checked their fulminations against Wyclif and the Duke of Lancaster, the Lollard preachers turned their sermons from the injustices done to the poor and spoke on Isaiah's text, "A little child shall lead them." The great nobles ceased their jealous strivings, and the London merchants amicably prepared to spend a prodigious sum upon their share of the coronation festivities.

On the Feast of St. Swithin, July 15, the day before the ceremony in Westminster, Richard's procession from the Tower through the City surpassed in magnificence any civic celebration ever seen.

Katherine viewed the procession from a tier of wooden benches which had been erected on West Chepe for the accommodation of privileged ladies. The Princess Joan sat on a dais, flanked by two of her sisters-in-law, Isabella of Castile, Edmund's frivolous and empty-headed wife, who was as unlike her sister Costanza as a chaffinch to a raven, and Eleanor de Bohun, the great heiress, Thomas of Woodstock's bride. Eleanor was a high-nosed girl with a mouth like a haddock, who fussed so loudly over some matter of precedence that Katherine could hear her acid complaints from where she sat at some distance from the royal ladies, with Philippa, Elizabeth and her own Blanchette. The Swynford children had been brought down from Kenilworth for this extraordinary occasion, and her little Tom by special favour of the Duke had been permitted a place in the procession amongst the nobly born boys of approximately Richard's own age.

St. Swithin, doubtless propitiated by countless prayers, had in the morning duly cleared some threatening rain clouds from the sky, and the afternoon was as dazzling as the white silk banners and the cloth of silver draperies that were festooned along the line of march.

On the Chepe the great open conduit, new-painted in blue and gold, gurgled pleasantly near the grandstand, and the heat grew such that Katherine sent a page over with a flagon to be filled. The conduit, for the three hours of the procession, ran with wine. Good wine, and even young Philippa drank thirstily before resuming her sedate composure.

Elizabeth fidgeted and yawned as detachment after detachment of the Commons walked past City wards, all garbed in white in honour of the child king.

Blanchette sat quietly beside her mother. Her wondering eyes moved from the marching men to a gold-painted canvas tower where four gold-costumed little girls of her own age were perched in the turrets and in great danger of falling out as they hung over the flimsy parapets.

The Commoners had all disappeared down Pater Noster Lane and the men of esquire rank were filing past when Blanchette leaned forward and said, "Th-there's Uncle Ge-Geoffrey," with the little stammer in her speech which had developed during Katherine's last absence from Kenilworth.

"So it is, darling!" her mother answered, staring at the rotund figure in the white linen over-robe that made him look comically like a Cistercian monk. She had not seen Geoffrey in months, for he had been again in France on King's business. As his file of esquires passed the ladies' stand, he looked up and waved at them, then peered quickly along the benches looking, no doubt, for his wife. But Philippa Chaucer was not there.

The Duchess of Lancaster would attend the coronation tomorrow and was even now en route from Hertford with her ladies, including Philippa, but a secular parade did not appeal to her.

The knights and knights banneret followed the squires, then the aldermen, and the new mayor - the wealthy grocer, Nicholas Brembre. He complacently curbed his prancing horse with as much negligent skill as any knight, while he bowed to the stand where his lady mayoress Idonia was ensconced on silver cushions at a place of honour near the Princess Joan.

"He looks almost a gentleman, except he's so greasy and sweaty," said Elizabeth of the mayor in a shrill astonished voice.

"Hush, Bess," said Katherine sharply. "Gentlemen sweat too, in heat like this."

"Not my father's grace," retorted Elizabeth pointing proudly. "He's never slobbery, no matter what."

Katherine bit her lips against a laugh, for Elizabeth was quite right. The lesser earls and barons had passed by and Richard's uncles, led by the Duke, had appeared at the curve by Chepe Cross. In cream velvet trimmed with silver and riding on a snow-white horse, John gleamed as immaculate as an archangel. His brothers, the pale slouching Edmund, and the swarthy bull-faced Thomas, seemed to Katherine like a couple of nondescript rustics by comparison.

She had no opportunity to admire John as she wished or to respond properly to the bow he sent in their direction, for as the little King approached in a blare of herald's trumpets and the rattle of drums, the ladies surged to their feet amidst cheers and roars of "Long live Richard!"

The small girls in the canvas castle were prodded from below and in a sudden frenzy began to fling out gold florins and tinsel leaves across the King's path. Someone hidden in the tower pulled a string so that a canvas angel with jerking arm brandished a crown over Richard's passing head.

The boy looked up, startled, laughed, a high fluting tinkle audible even through the tumult of his acclaim.

The ten-year-old Richard was pink and white and delicate as an apple-blossom. His thistledown curls were yellow like a new-hatched chick. His shoulders seemed too slight for the vast white and brilliant-studded mantle they had draped on him, albeit he sat his horse sturdily and pricked it angrily with his golden spurs of knighthood when the beast lagged.

"By corpus, he looks like a maid," cried the irrepressible Elizabeth, examining her cousin critically. "I trust he'll cease to be such a mollycoddle, now he's King!" She had scant use for Richard, who was poor at games, liked only to mess about with little paint pots or to read, and clung to his mother's skirt when teased.

"Tomorrow he will be God's anointed," said Philippa severely, frowning at her sister. "You must not speak like that of the King's Grace."

Elizabeth subsided, faintly awed, so that Katherine could give her whole attention to the group of lads that followed Richard on foot. She singled Tom out first and showed him to Blanchette, aware that the child had drawn back and ceased to look at the procession as the Duke rode by. "Look, sweet," she said taking her daughter's hand, "how bravely our Tom marches with all the young lords." And how much he looks like Hugh, she thought with a pang. The dusty-looking crinkled cap of hair, the square Saxon face, the forthright stride - these were all from Hugh, so was the boarhead-crested dagger that dangled on his hip. The Duke had given him a far handsomer dagger, but Tom obstinately preferred his father's.

"He's m-much t-taller than L-lord Henry, though he's younger," said Blanchette. Katherine squeezed the passive little hand and agreed, but she sighed. Blanchette's pride in her brother was natural enough, yet this remark, like nearly everything Blanchette said, showed her animosity to the Duke and all who belonged to him. Well, she would have to get over it, thought Katherine with sudden impatience.

The two Hollands came cantering up at the tail of the procession, waving their great swords and crying to the people to stand back and wait until the King had passed the cathedral before they rushed to the wine fountains. These two young men were the Princess Joan's sons by her first husband and, beloved as Joan was, no one felt that they did her much credit, except apparently Elizabeth, who had recovered from Philippa's reproof and pointing at the younger Holland, John, said, "There's a comely lusty-looking man! 'Tis Jock Holland. He picked up my glove when I dropped it t'other day at Westminster. Nan Quilter," she added admiringly, "says he has more paramours than any other man in London."

"Elizabeth, you're disgusting!" cried Philippa. "Must she for ever tattle servants' gossip, Lady Katherine? You must find some way to refine her tastes."

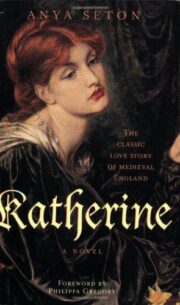

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.