Sanctity, the clergy said. Prayer. The practice of religion. The benevolence of the holy saints. The Grace of God.

Katherine rose and walked to the Prince of Wales' prie-dieu in the corner beyond the armour. A gilt, elaborately enamelled triptych hung above the prayer desk. The centre panel depicted Calvary, the side ones snowed various tortures of the damned. These were intricately detailed: naked bodies writhed in orange flames, and from severed limbs and seared eyes dripped ruby gouts of blood. The Christ's face on the Cross expressed only contorted agony and above the panels was written, "Repent Ye!"

She gazed at the triptych with repulsion. Here was no message of steadfastness. Here naught but warning and more fear. Her rebellion grew, and she wondered, What guidance do we truly get from the saints or even from the Blessed Mother and Her Son? Why did not they, or St. John, protect my lord from harm?

What of the vow she herself had made to St. Catherine in the storm at sea? Had the saint in truth really saved her? And this vow she now felt had had nothing to do with heavenly guidance. The necessity of faithfulness to Hugh, however bitter, had sprung from her own self-esteem, her own integrity. For I believe, thought Katherine, there is nothing beyond or above ourselves.

At once - and for an instant she was frightened - she heard plain in her head how Brother William would cry "Heresy!" in his stern tired voice. Then she forgot her painful questions and ran to the bedside, for John stirred and said, "Katrine?"

"My lord," she whispered, bending over him.

His eyes were clear as the sky of Aquitaine, and the smile he gave was one she had not seen in long. He reached his arms up and pulling her down kissed her hard on the mouth. Then he sat up and yawned and said, "Christ, what a sleep I've had -" He looked at the curtained window. "Is't dark still?'

"Again!" she answered smiling. "You've slept the day through."

"By the rood! And did I then?" He scooped his hair back from his forehead and stretched prodigiously. He ran his tongue around his mouth and said, "Dry as tinder. It seems that I was drunk last night - it seems to me too that I babbled much nonsense." He quirked his brows and looked at her half laughing.

"You don't remember?" she said softly.

"Nay - only that you were near me, and most patient. And that I love you, sweet heart." He pinched her cheek and grinned at her. "I shall prove it soon - but not in this gloomy bed. Lord, what a dismal room. We must get back to the Savoy."

He got up and walked into the garde-robe. She heard him whistling beneath his breath and the splashing of water. "Send for food, lovedy," he called to her, "I'm famished."

She picked up the hand-bell and rang it. There was a pause before it was answered, for the page, who stood ever ready in the passage, had been given orders.

When the door opened, it was the Princess who came in, and with her was her chief adviser, Sir Simon Burley, a grave-eyed conscientious man whose grizzled beard waggled anxiously as he said, "The Duke's awake?"

Katherine nodded and gestured towards the garde-robe. John walked out, his face and neck still aglow from the vigorous sluicing he had given them. "Good evening, Joan," he said to his sister-in-law. "Did you think you had old Morpheus himself for guest?" He turned to Burley, "And you, Sir Simon, I see by that long face that there's more ill news. Can't it wait until I'm fed?"

"My lord, of course, but you should know that a deputation of Londoners have gone off to Sheen, to the King's Grace to beg him to reconcile your quarrel with the City. They know your troops are massing at the Savoy. The-people are affrighted."

"And so they should be," said John with calm sternness, "and shall make just reparation."

The Princess and Burley glanced at each other both remembering the terrible rage of yesterday, the threats of war, of violation to St. Paul's, of murdering revenge.

"What is just reparation, my lord?" said the Princess nervously.

"By corpus' bones, Joan! I'll decide that when I've got to Sheen and heard what they offer. Certain it is our poor father won't know what to do. My sweet sister, have your cooks all been drowned in the Thames? Or shall I roast a leg of yonder chair myself over the fire?"

The Princess laughed and called orders to the hovering page.

"My lord," she said, her fair fat face all a-quiver with relief, "you sound yourself again. Your sleep did great good." Impatience, arrogance and sternness he showed as always, but she saw that the wild consuming unreason had left him, and she sent Katherine a look of deepest gratitude.

CHAPTER XXI

Neither Katherine nor the Duke ever mentioned the night at Kennington Palace, though it had an immediate effect on their relationship.

His need for her deepened, he talked to her more freely about all his concerns, and he kept her with him constantly, showing her many public as well as private signs of his love.

Katherine bore herself with discretion, but all of the Duke's meinie, and soon many others outside, grew aware of her new status. At the Savoy, her lodging was changed from the Monmouth Wing, nor was she put in the small room near the Privy Suite which she had occupied on earlier visits. She was given the Duchess' small solar adjacent to the State Chamber, while her nights were spent with John in the Avalon Chamber's ruby velvet bed. At the High Table in the Hall her seat was shifted to one next to the Duke, and though decorum was observed by the vacancy of the Duchess' place to his right, it pleased John to order for Katherine a chair no less magnificent than his own, with gilt carvings, topaz velvet cushions, and her embossed Catherine wheels for a headrest.

These elevations naturally set many spiteful tongues to wagging, but they wagged in secret, not only for fear of the Duke, but because the Princess Joan made plain her tolerance of the situation and treated Lady Swynford with marked favour.

The Duke had received the frightened London deputation at Sheen and after listening to their apologies and extenuations, had exacted mild enough punishment - a public penitential procession to St. Paul's in which the City dignitaries should carry a candle painted with his coat of arms - and had ordered that the unnamed instigators of the disturbance should be excommunicated. When these orders had been grudgingly obeyed, he saw to it that the obnoxious parliamentary bill to curtail the City's liberties was quietly dropped. When the people demanded a fair trial for Peter de la Mare, who was still imprisoned in Nottingham, this was granted. In the course of some weeks the Speaker of the Commons was released and rode in triumph back to London.

Against William of Wykeham the Duke's hostility lasted longer, since he was not adverse to making an example of the bishop as a lesson to the episcopal party.

Upon finding the Duke implacable, Bishop Wykeham bethought him of another method to regain his rich temporalities, and by the promise of a colossal bribe to Alice Perrers, convinced that lady, and through her the King, of the injustice of his pitiable poverty. King Edward duly signed a bill for Wykeham's restitution.

John when he heard this was displeased, but he shrugged and let the matter rest. This happened in June when the King was obviously failing and there was a great deal else to be thought of besides the chastisement of one fat greedy bishop.

Katherine was interested to hear of these various clement measures and gradually began to understand something of the conflicting ambitions and turbulence which made difficult any clear cut policy.

But in the matter of Pieter Neumann's fate she felt vivid personal concern. And on this one topic, John would not speak to her. She saw that the hidden wound, though purged of its prurience and healing rapidly, yet would always leave a sensitive scar, and she forbore any mention of Pieter, though she ached to know what had been done with him.

She found out at last in Easter-tide, on Maundy Thursday after the foot-washing ceremony. On this Thursday the act of humility in imitation of the Blessed Christ was performed throughout the Christian world in palaces, monasteries and manors, and at the Savoy the line of beggars began to form in the Outer Ward directly after Mass. It was customary to number the poor by the age of the lord who would humble himself to them, but the Duke magnificently augmented his own thirty-seven years by the ages of his three Lancastrian children, thus making forty additional ragged and filthy candidates to be honoured.

The ceremony took place in the Great Hall and Katherine stood watching at one side of the dais where the paupers, looking both proud and frightened, were seated on benches, and tittered nervously as the great Duke of Lancaster commenced the washing of their dirty scabrous feet.

The Duke was dressed in a humble russet tunic devoid of ornament. Two squires held silver basins of warmed rosewater, and Robin held a towel. The Duke smiled gravely at his paupers and worked quickly and conscientiously. He made the sign of the cross on each foot, then kissed the toes, while murmuring the words of humility.

Upon dismissal the owners of the feet went on to material rewards. On a table by the kitchens stood vats of broken meats and bread, from which the paupers were permitted to fill large sacks, and at the door the Duke's almoner doled out pieces of maundy silver.

When the ceremony was concluded and the gratified paupers had begun to gabble and bicker amongst themselves, the Duke came to Katherine and said, "Shall we visit the mew, sweet heart? Twill smell far better than in here, and we must see how your little merlin does."

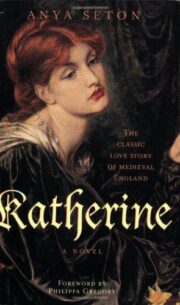

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.