The bishop's mouth fell open. His jowls quivered, his voice was shrill as he cried, "Your Grace, why do you prosecute me? There are many other bishops - you've always shown me favour before - -"

The Duke's eyebrows raised slowly. He folded his hands on his lap and gazed back at the flushed sweating face beneath the jewelled mitre.

"It cannot be," cried the bishop, suddenly perceptive, "that you believe I had aught to do with that preposterous changeling story!"

"The scroll said that you had this secret of my true birth from Queen Philippa on her death-bed." The Duke spoke so soft, the members of the council strained to hear, and the bishop stared with stupefied eyes.

"But the Queen confessed no such thing, Your Grace! 'Tis all a lie!"

"That I know, my Lord Bishop. But someone started this he. Your name was written."

"By the Holy Trinity, it wasn't I. You must believe, Your Grace, it wasn't I!"

The Duke shrugged. "Yet you've admitted your memory is faulty." He glanced at his council. "The trial will proceed."

It proceeded and soon ended. The Bishop of Winchester was stripped of his rich manors, and his coffers full of gold. At one stroke all his worldly possessions were removed from him - though his episcopal office even the Duke could not touch - for that had come down through St. Peter from God.

The Duke's retinue rejoiced. They swaggered and boasted of their lord's power. They laughed openly at the whole lot of discomfited bishops. In the taverns and halls and on the streets they jeered also at the Commons, and at the cocky bantling Peter de la Mare who had thought to defy the Duke and now found himself rotting in a dungeon.

Alone of all Lancaster's knights, Baron de la Pole had reservations. He had expressed them to the Duke and been sent away from Havering for his pains. On a November morning in his chamber at the Savoy he was gloomily letting his squire array him in hunting costume when his page announced Brother William Appleton, and the barefoot friar walked in.

"Well now, Brother," cried the baron heartily. "I'm glad to see you. How was it at Pontefract, are you just back?"

"Some time ago," said the Franciscan. "I've been staying with my brethren at Greyfriars. I hear strange things of his Grace."

"Not so strange!" said the baron, instantly defending his Duke. "He but vindicates his honour like any noble knight!"

"I hear," said the friar, "that no act of the last Parliament has been suffered to stand, that the Speaker is imprisoned, the Earl of March banished."

"It is so," said de la Pole.

"I hear that the Bishop of Winchester is homeless, virtually begging his bread from door to door."

"Like a friar, my dear Brother, like a friar!" de la Pole laughed. " 'Twill do the fat bishop no harm! And remember" - the baron leaned forward - "it is to little Prince Richard that he gave all the bishop's confiscated lands. That should stop their foul talk of plots against the child."

"Nothing but a miracle will stop talk. The Duke's acts are-frightening the people."

The baron sighed and, sitting on a stool, held his legs out for his squire to put on his leather hunting shoes. "He no longer cares. He wants only revenge."

"Has he not had enough?" said the friar sternly.

" 'Twas that placard. He knows not who put it there, or wrote it. So he strikes out blindly. 'Twill be Bishop Courtenay next. A tougher stick to break than Winchester was, and for this he's using Wyclif."

The friar nodded. He had heard Wyclif had been preaching in the London pulpits, preaching his doctrine of church reform and church taxation so that the burden of the people's own taxes might be lessened.

"An honest man, Wyclif," said the friar thoughtfully, "and his teachings touched by Holy Truth, I think, but they may dangerously inflame the commons - -"

"Lancaster too is an honest man!" broke in the baron, "though hot of temper like all his race. And still he's shown forbearance. Mind you, Sir Friar, there's been no bloodshed!

He's even checked the King's whore in her clamour to kill de la Mare."

"Bloodshed-" The friar smiled faintly. "Blood is all you knights understand. There are far worse sufferings. But 'tis not of that I'd speak." He glanced at the baron's squire who was polishing the tip of his master's spear. The baron took the hint and waved dismissal.

Brother William sat down on a stool and explained. "All this that we've been saying is common knowledge. I'll not spread any rumour that is not. 'Tis about that placard. I believe I know who wrote it."

"God's nails - -" breathed the baron, sinking back open-mouthed in his chair. "Do you indeed? His Grace has sent spies throughout the city to listen in the taverns and question offhandedly, but to no purpose."

The friar hesitated. This knowledge had not come to him through any secrets of the confessional, for if it had his lips would have been as sternly sealed as they were on another matter relating to the Duke. Shortly after his return to London from the north, he had been called to examine a sick monk at St. Bartholomew's Benedictine priory, so great was his reputation as leech that even the monks called on him at times.

As he had left the priory infirmary, he had been shocked to hear drunken voices coming from the scriptorium and a bleating laugh like a goat's. He had been about to hurry past the door, thinking that the prior kept lax rule here, when the same bleating voice called out, "And this one'll hang on Paul's door too, 'tis better than the changeling - -"

Someone said "Hist!" and there was a sharp silence.

The friar walked into the scriptorium. Two monks, their foolish young faces red with the ale they had shared from a mazer, gaped at him blankly. The third man was perched on a high stool at a desk, a quill in his hand, a square of parchment under it. His robes and semi-tonsure showed him to be a clerk. His pock-marked face instantly became bland as cheese, but his little eyes fastened on the friar with ratlike caution.

"You make merry in here while you inscribe your scrolls?" said the friar pleasantly, trying to edge near enough the desk to see what the clerk had written. "You treat of merry topics, Sir Clerk?"

One of the monks in evident confusion said, "This clerk is none of us, he but lodges here at the priory. He has lately come from Flanders."

"Nay, I'm an Englishman - of - of Norvich," said the clerk quickly in his bleating voice. "Johan of Norvich, I but spent a time in Flanders."

"Johan?" said the monk in surprise. "We've called you Peter - -"

"Johan - Peter - both." The clerk slid off his stool, and the friar with keen disappointment saw that the scroll was blank but for two words "Know ye - -"

"Is't the custom at St. Bart's that Grey Friars haf right to nose around and question us?" said the clerk to the monks, and limping to the mazer he took a long draught.

The Grey Friar had made some civil remark and gone, but he had been mulling this matter over in his mind ever since. He had consulted his superior, he had prayed on it, and now, knowing the baron's loyalty and shrewdness, he had come to him.

He told the baron what he had overheard, but added, "There's no proof, they'd say I heard wrong, the parchment with the two words will have vanished. And there is much that's puzzling. Whate'er this clerk may call himself, he spoke with Flemish accent. And never had I seen malice so pure in a man's eyes. What can he have so harsh as this against the Duke? The young monks are fools and swayed by this man, though willing enough to spite Wyclifs patron, no doubt."

"The clerk is being bribed?" suggested de la Pole. "By March? Or Courtenay?"

"Ay - mayhap - he had gold rings on his fingers - but the nub of the matter is - shall I go with this tale to the Duke?"

The baron pondered. "Not now. There's no proof, and the Duke may be led to more blind violence. His rage is nearly slaked, 'twill all die down - if nothing further happens. The clerk and Benedictines maybe will bate their tricks, since they must guess you heard them."

Nodding thoughtfully and with relief, the friar stood up. It went against his grain to carry tales that he had got by eavesdropping and he decided to wait for developments. It might well be too that the Duke would not receive him, since they had parted last on a discordant enough note.

This reminded him of something and he said, "How is't with Lady Swynford? What part has she played in all this coil of His Grace's?"

"None at all," answered the baron. "I doubt that he's seen her since it started." His face softened. "Poor fair lass, she moped here at the Savoy for days and then returned to Kenilworth, with the ladies Philippa and Elizabeth. And yet it seems he loves her dearly when he has a mind for love."

"A vile adulterous love," said the friar grimly, pulling up his cowl and adjusting the knotted cord at his waist. "God will scourge them for it."

CHAPTER XIX

Katherine kept Christmastide alone with the children at Kenilworth. The Duke divided his festivities between his father at Havering and his nephew, little Richard, who remained with the Princess Joan across the Thames at Kennington.

His establishment at Kenilworth was not, however, entirely forgotten. In February, the Duke sent belated New Year's presents to everyone, and a silver-gilt girdle for Katherine herself, but the accompanying note was stilted, though it indicated that she should return to the Savoy for a visit with the Lady Philippa, that there was an envoy coming from the Duchy of Luxembourg who wished to see Philippa with a view to possible marriage negotiations.

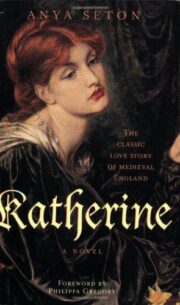

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.