That night at the Savoy uneasy speculation hummed. In the kitchens and cellars the varlets whispered together, and the men-at-arms in their barracks. The chancery clerks and the chapel priests buzzed as unceasingly as did the Duke's squires, or the knights and lords who headed his retinue. The Duke had gone to Havering-atte-Bower to see the King. He had put off his mourning clothes and ordered his fastest horse to be saddled. Galloping as though Beelzebub's own fiends pursued him, he had set off for Essex. He had chosen none of his men to accompany him, nor spoken to anyone: he had gone alone. This, a circumstance so unprecedented and foolhardy, that Lord de la Pole, anxiously frowning, spoke of it in the Great Hall that night. "God's wounds! Who can guess what's in his mind? He's like a man bewitched!" He spoke to Sir Robert Knolles, another old campaigner who had served with the Duke for twenty years.

Sir Robert gnawed on his grizzled moustache and cried staunchly, "Why, he will avenge this insult to his honour. What man can blame him?"

"Yet such paltry nonsense," answered de la Pole. "They've whispered far worse of him than this farradiddle about a butcher's son, or even that he plots for the throne."

"Whispered, ay," said the old knight, "but this was written down."

De la Pole was silent. He himself, who could read a little, had awe of the written word, but to the common folk writing was a sacred oracle.

"By God!" cried de la Pole, angrily banging his hand on the table. "No one who saw him today could doubt him a Plantagenet! D'you remember Prince Edward's face at Limoges massacre? No mercy, and no quarter when the fury's on them."

"But that was war," said Sir Robert. "His Grace can hardly massacre the whole of London."

"Nay, and our Duke has a keener mind than his brother ever had. He'll find subtler means of vengeance. But," he added frowning, "I cannot guess what."

Katherine, sitting at her old place at the High Table, heard this conversation, and her troubled heart grew heavier still. Her hurt that he had no more thought of her than for the rest of his meinie was eclipsed by her suffering for him. She had read the placard. The shock it gave her was not at its absurd content but at the vicious hatred which had prompted it. And she who knew John better than anyone, guessed at some uncertainty, or fear. She thought of the night at Kenilworth, when he had said, "I've been tilting with a phantom."

Her unhappiness culminated later in violent anger at Hawise. Katherine turned on her maid the moment their chamber door was dosed and they were alone. "It was your Jack, the whoreson churl, who shouted insults at my Lord!" she cried. "No doubt you knew it. You faithless slut, no doubt 'tis nothing to you to take the Duke's bounty, while your own man sneers at him and yammers filthy lies!"

Hawise gasped. "Don't, sweeting, don't," she cried. "I didna know till now that Jack had aught to do wi' that scrummage today. And God help me, but I love ye better'n him or mine own child. 'Tis in part for this that Jack do hate the Duke."

Katherine turned and flung her arms around the stout neck. "I know, I know. Forgive me," she cried. "But if you had seen my lord standing there - -alone - on the step - I would have shielded him - I couldn't-"

"Hush, poppet, hush." Hawise stroked the wet cheek and made the gentle soothing sound she used to Katherine's babies. I'll speak sharply to Jack when I see him, she thought, but Jack cared little what she said any more. Since she had left him to serve her lady he had taken some Kentish wench to live with him.

" 'Tis nothing so grave after all, sweeting," she said. "Jack was tipsy, no doubt, and meant no real harm. The Duke didn't know who 'twas shouting?"

Katherine shook her head. "Only I up there would've known him. And my lord was dazed, you could see. Oh, Hawise-" She shut her eyes with a long unsteady breath while the maid's thick nimble fingers set to unfastening her brooch and girdle.

"Sleep now," said Hawise, "for 'tis late, and shadows cast by candle are vanished in the sun. The Duke'll be back here wi' ye on th' morrow, I'll take oath on't."

All through that autumn the Duke stayed at Havering Castle with the old King, who received him with delight, clung to him and mumbled gratitude to his dear son. For the Duke at once recalled Alice Perrers. He sent the King's own men-at-arms to fetch her from her place of banishment in the north. He met her in Havering courtyard himself and gave her his hand in greeting.

In jewels and brocades and a whirl of musk, Alice flounced triumphantly out of her chariot, her three little dogs frisking and barking after her. She raised her thickly painted face to the Duke.

"This is different, Your Grace," said Alice with her sideways smile as she curtsied, "from that time at Westminster when you did bow to Commons and send me away. I thought you could not mean it." Her wooing voice caressed him, she squeezed his hand softly.

He withdrew his hand. "Dame Alice, much has changed since that day in the Painted Chamber, and now I bow to no man - or woman." He looked at her in such a way that she was frightened, and she nodded quickly.

"My lord, I'll do your bidding in everything. I've some influence in my own fashion; but I - I - I do beg of you one more boon."

He inclined his head and waited.

She breathed sharply, her green eyes narrowed. "I crave the head of Peter de la Mare," she said, watching the Duke closely yet sure of her ground. "I did not like the things he said of me, my lord."

The Duke laughed, and Alice involuntarily stepped back.

"The Speaker of the Commons already lies in chains in Nottingham Castle dungeon," he said. "I shall decide what's to be done with him after I deal with other matters. You may go now to the King."

One by one and day by day the Duke of Lancaster reversed all the measures which the reform Parliament had put through in the spring. He summarily dismissed the Privy Council that the Commons had appointed. The Lords Latimer and Neville were released from their confinement and reinstated at court. The merchants impeached by Commons were released from jail.

The old King signed whatever papers his son gave him, much pleased that his beloved Alice and John were now in agreement, and mistily aware that he was helping to punish a pack of upstart rebels who had dared to interfere with royal prerogatives.

The Duke stayed in Essex at Havering Castle with his father, but after the first few days of inner frenzy, his mind regained control. His purpose became a staunch ship, steered by his skilful brain, and gliding relentlessly forward along the cold channel of his fury.

He had the force of the King's authority and the King's men behind him, and backed it by his own equally powerful Lancastrian feudality. He summoned key men of his retinue to Havering, he kept messengers galloping in a constant stream between Havering and the Savoy. He sent them farther afield to the far-flung corners of his vast holdings. From Dunstan-burgh in the north to Pevensey in the south, from his Norfolk manors in the east to Monmouth Castle on the Welsh border - the stewards and constables were alerted to be ready in case of need.

But there was no need. Commons had dissolved long ago. The members had scattered to their homes all over England. Their Speaker was imprisoned, and the lords and bishops who had given them support now wavered one by one and attached themselves to the winning side.

All but the Earl of March and Bishop Courtenay of London.

The Duke let the bishop be, for the present. Courtenay he would deal with later, and he had a special weapon in mind. But for the proper punishment of March, one ally was essential. The Duke summoned to Havering the powerful Border lord, Percy of Northumberland, and in an hour's secret conference showed him plainly where self-interest lay and how worthless had been March's promises.

The frightened little Earl of March thereupon was ordered to leave the country on foreign service. He refused. Assassination on shipboard or in Calais seemed to him quite as possible as the already accomplished imprisonment of his steward in Nottingham dungeon. Instead he resigned his marshalship of England and fled across the country to barricade himself in Ludlow Castle.

The Duke rewarded Percy's rejuvenated loyalty to the crown with the abandoned Marshal's staff.

These measures it soon appeared were but preliminaries.

At the end of October, the Duke attacked William of Wykeham, the Bishop of Winchester. He summoned him before the new Lancastrian Privy Council on charges of graft, and robbery of the public funds.

So one morning the corpulent fifty-four-year-old bishop stood before the King, the Duke and the members of his council, facing them all with more bewilderment than anger. He had always been in high favour at court, he had been the King's chaplain, the King's architect, the Queen's confessor, and Chancellor of the Realm. He had had no enemies until now.

His podgy fingers tightened on his crosier; beneath his gorgeous red satin cope his portly belly rumbled with nervousness.

"I cannot understand, Your Majesty," he began his defence to the King, but seeing that his old patron's wrinkled eyelids had shut and the grey, crowned head was nodding, he turned to the Duke. "Your Grace - these charges, they're outrageous! They deal with matters ten years gone."

"But they were true - my lord bishop?"

"By the Blessed Virgin, how can I remember after all this time how I came by every groat? 'Tis impossible, my lord."

"Maybe your memory will sharpen if you be relieved of the clogging burden of your revenues and temporalities," said the Duke. "Holy poverty is much desired by the clergy, I believe." He glanced to the corner of the chamber where stood a priest in plain dun-coloured robes, John Wyclif, whom the Duke had called here from Oxford. They exchanged a grave slight smile.

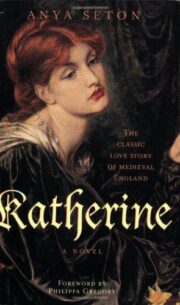

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.