She caught its echo only because of the buzzing of the people around her. The Duke had commanded that all those who had not previously been presented to the Queen of Castile should come up now as their names were called.

This too, she thought - he wishes to humiliate me, to see me pay homage to his wife. And she steeled herself in anger. One by one, lords, knights, and their ladies were summoned by the chamberlain.

Then she heard "Lady Katherine Swynford." She walked stiff kneed down the Hall, her cheeks like poppies. There were snickers quickly checked, and she felt the slyness of spearing eyes.

She reached the Duchess's chair and curtsied low, touching the small cold hand extended to her, but she did not kiss it. She raised her eyes as Costanza said something quick and questioning in Spanish, and she heard the Duke answer, "Si."

The women looked at each other. The narrow ivory long-lipped face was girlish and not uncomely, but seen close like this one felt only its austerity. The black eyes glittered with a chill fanatic light. They seemed to appraise Katherine with the scrutiny of a moneylender examining a proffered trinket,' and again Costanza spoke to the Duke.

He leaned slightly towards Katherine, saying, "Her Grace wishes to know if you are truly devout, my Lady Swynford. Since you have the care of my daughters, she feels it essential that you neglect not religious observance."

Katherine looked at nun then, and saw behind the sternness of his gaze a spark of amusement and communion.

Her pain ebbed.

"I have tried not to neglect my duties towards the Ladies Philippa and Elizabeth," she said quietly.

The Castilian queen understood the sense of this, as indeed she understood far more English than she would admit. She shrugged, gave Katherine a long enigmatic look, waved her hand in dismissal as the chamberlain called another name.

Katherine quitted the Hall, walked slowly across the courtyard. Oh God, I wish I hadn't seen her, she thought; yet he doesn't love her, I know that. No matter that she is so young and a queen, it's me that he loves, and it does her no real wrong - and she doesn't care - one can see it, and she cannot even bear him a son. Yet, Blessed Virgin, I wish I had not seen her.

Throughout the sleepless night in her lonely bed, Katherine's thoughts ran on like this.

CHAPTER XVIII

The Duchess Costanza that night announced to the Duke that she wished to make pilgrimage to Canterbury at once. It was for this that she had come to London. Her father, King Pedro, in her dream had directed her to go, and also told her certain things to tell the Duke.

"He reproaches you, my lord," said Costanza to John when they were alone in the state solar. Her Castilian women had been dismissed for the night, having attired her in the coarse brown robe she now wore to bed. Her large black eyes fixed sternly on her husband, she spoke in vehement hissing Spanish. "I saw my father stand beside me, groaning, bleeding from a hundred wounds that traitor made in him. I heard his voice. It cried, 'Revenge! When will Lancaster avenge me?' "

"Aye," said John bitterly, "small wonder he cries out in the night. Yet twice I've tried - and failed. The stars have been set against us. I cannot conquer Castile without an army, nor raise another one so soon."

"Por Dios, you must try again!"

"You need not speak thus to me lady. There's nothing beneath heaven I want more than Castile!"

"That Swynford woman will not stop you?" she said hoarsely. Into the proud cold face came a hint of pleading.

"No," he said startled, "of course not."

"Swear it!" she cried. She yanked the reliquary from beneath her brown robe. "Swear it now by the sacred finger of Santiago!" She opened the lid and thrust the casket at him. . He looked at the little bleached bones, the shreds of mummied flesh and thick, ridged nail. "My purpose needs no aid from this."

She stamped her foot. "Have you been listening to that heretic - that Wyclif? In my country we would burn him!" Her shaking hand thrust the reliquary into his face. "Swear it! I command you!" Her lips trembled, red spots flamed on her cheek-bones.

"Bueno, bueno, dona," he said taking the reliquary. She watched, breathing hard, as he bent and kissed the little bones.

"I swear it by Saint James." He made the sign of the cross. "But the time is not ripe. The country is weary of war, they must be made to see how much they need Castile. They must" - he added lower and in English -"regain their faith in me as leader. Yet I think the people begin to look to me for guidance. They say that in the city yesterday they cheered my name."

She was not listening. She shut the reliquary and slipped it back under her robe. "Now I shall go to Canterbury," she said more quietly. "My father commanded it. It must be that since I am in this hateful England, an English saint is needed also for our cause. I shall see if your Saint Thomas will cure me of the bloody flux, so I may bear sons for Castile."

The Duke inclined his head and sighed. "May God grant it, lady." But if, he thought wryly, 'tis not God's will that I should lie soon with her again, I shall submit with patience.

He held out his hand to Costanza, and with the ceremony she exacted and which he accorded to her rank, he ushered her up the steps to her side of the State Bed. He held back for her the jewelled rose brocade curtains. She thanked him and, shutting her eyes, began to murmur prayers. Her narrow face was yellow against the white satin pillow, and his nostrils were offended by her odour. Costanza's private mortifications included denial of the luxury of cleanliness, Beneath the requisite pomp of her position, she tried to live like a holy saint, contemptuous of the body.

In the first years of her marriage she had not been so unpleasing. Though she had brought to their bed only a rigid endurance of wifely and dynastic duty, still she had allowed her ladies to attire and cleanse her properly at all times, and taken pride in the smallness of her high-arched feet, the abundance of her long black hair. She had been quieter, gentler, and though they had soon ceased, there had been moments when she showed him tenderness, had once spoken of love, which greatly embarrassed him. Only once however. And since the birth and death of the baby boy in Ghent she had become like this, indifferent to all things but her religious practices, her strange dreams and her consuming nostalgia for Castile.

John climbed into his side of the great bed, glad that space enough for two separated them.

He heard her whispering in the dark, "Padre, Padre - Padre mio - -" and his flesh crept, knowing that it was not God, but the ghost of her own father that she supplicated.

Yet Costanza had no tinge of madness. Brother William had said so, three weeks ago when John had sent him to Hertford to examine the Duchess. "Disorders of the womb do oft-times produce excitable humours in the female," the Grey Friar had reported. "I've given Her Grace a draught which may help her, but her Scorpio is afflicted by Saturn. That is not all that afflicts her," added the friar with stern unmistakable meaning.

"Her Grace is nothing disturbed by my - my association with Lady Swynford!" John had answered hotly. "She has never suffered from it, nor does she care."

"Perhaps not, my lord. But God cares - and the sin of adultery you live in now is but the stinking fruit of the viler crime which gave it birth."

"What's this, friar?" John had shouted in anger. "Do you join my enemies in the yapping of vague slanders - or is it that your bigot mind sees love itself as such a vileness? Speak out!"

"I cannot, my lord," said the friar after a time. "I can but remind you that Our Blessed Lord taught that the wish will be condemned even as the deed."

"What wish? What deed? You babble like a Benedictine! You had better stick to leeching."

"Do you pray sometimes, my lord - for the salvation of Nirac de Bayonne's soul?" said Brother William solemnly.

Until now, when Costanza's behaviour had reminded him of Brother William, John had put this conversation from his thought, deeming that the friar, like all the clergy, puffed himself up with the making of dark little mysteries and warnings. He had answered impatiently that no doubt Masses had been said for Nirac in St. Exupere's church in Bayonne, since money had been sent there for that purpose. He had resented the friar's steady accusing gaze and said, "It was not my fault that the little mountebank's wits unloosened, or that he dabbled in witchcraft! You weary me, Brother William."

"Aye," said the friar, "for you've a conscience blind as a mole and tough as oxhide. Beware for your own soul, my Lord Duke!"

No other cleric in the world could have thus spoken without instant punishment, and the rage that injustice always roused in John had hardly been controlled by the long liking and trust he had for this Brother. But he had sent the friar away from the Savoy before Katherine came. Sent him far north to Pontefract Castle, where the steward had reported several cases of lung fever.

At the thought of Katherine, John stretched and smiled into the darkness. Tomorrow night she would be here with him again, since Costanza was leaving for Canterbury. Nay - not tomorrow night, for that was sacred to the memory of Blanche and would be spent in mourning and fasting, as always on this anniversary. The next night then. He hungered for Katherine with sharp desire, picturing her as she would be now in her bed - white and rose and bronze, warmly fragrant as a gillyflower.

The Castilian Duchess left the Savoy next morning with six of her own courtiers and a few English servants. She was dressed in sackcloth, her head was powdered with ashes and she rode upon a donkey, for that was the humble beast used by Our Blessed Lord.

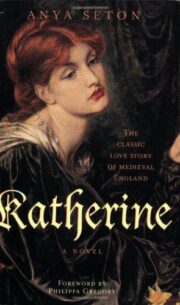

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.