John knelt by the couch. His own eyes were moist, while he silently kissed his brother's swollen hand.

Very soon the Commons began to show its mettle. A delegate requested that certain of the lords and bishops might join with them in conference in the chapter house. The Duke agreed graciously and waited with sharp interest to hear their choice, nor was surprised that amongst the twelve men named were two of his bitterest enemies, his nephew-in-law, the Earl of March, and Bishop Courtenay of London.

The earl, still at twenty-five pimply and undersized, had never forgiven the slight Lancaster had put upon him after the Duchess Blanche's death, when he had been kept cooling his heels in the Savoy. Each year his jealousy had grown and was now reinforced by fear. March's two-year-old son, Roger Mortimer, was heir presumptive to the English crown, after Richard. Unless the dastardly Lancaster should plot to force the Salic law on England and grab the crown himself. For Roger's claim came through his mother. This fear added fresh fuel to March's loathing; and the earl, upon hearing his name called, looked up at the Duke with a sly triumphant sneer, which Lancaster received with a shrug. March was a poor weedy runt whose spite was worth no more return than bored contempt.

Courtenay was more formidable. As Bishop of London he was the most powerful prelate in the country after Canterbury, and the Duke's well-known views on Episcopal wealth and his association with Wyclif had long ago incurred Courtenay's hatred.

The Commons' choice of these two lords to bolster up their coming attack against the crown gave some measure of the difficulties ahead, but was not startling. The choice and the acceptance of Lord Henry Percy of Northumberland, however, was dismaying.

The lords remaining in the Painted Chamber settled back in an uneasy rustle of silks and velvets and let loose a buzz of consternation. Michael de la Pole detached himself from his fellows and coming up to the Duke said with the familiarity of long friendship, "By God's blood, Your Grace, what's got into Percy? The blackguard's gone over to the enemy! Yet a month ago he swore passionate love to you and the King!"

The Duke laughed sharply. "He has no enduring passion except for himself and his wild Border ruffians. He's swollen with pride and no doubt March has been puffing it with the hot air of promises."

He sighed, and de la Pole looking at him with sympathy said, "There's a vicious battle ahead, and I don't envy you the generalship."

In the ensuing days, the Commons' line of attack became abundantly clear. The first mine was sprung with the election of Peter de la Mare as their Speaker. De la Mare was the Earl of March's steward. He was also a blunt fearless young man who wasted little time in presenting reply to the chancellor's demand for a subsidy. What, he asked, had become of all the money already granted?

The people, de la Mare went on, were grievously dismayed at the shocking waste and corruption in high places, and they wished the guilty parties brought to justice. He stopped.

There was a long silence in the Painted Chamber. Everyone looked at the Duke, who finally said, inclining his head, "Indeed, if this be so, the people are within their rights. Who are those whom you would name, and what are their alleged crimes?" And he smiled with perfect graciousness.

The smaller fry were dealt with first: a customs collector, and the London merchants John Peachey and Richard Lyons, both accused of extortion, monopoly and fraud. These men were summarily tried, found guilty and sent off to prison.

Then, as the Duke and his friends had suspected, the Commons went for Lord Latimer. They accused him of a dozen peculations, of having helped himself to twenty thousand marks from the King's privy purse and finally of treason in Brittany.

Here John momentarily lost his calm and spoke out in anger, for Latimer, however unattractive a personality, had been his friend, and though he was quite probably guilty of malversation, the accusation of treason the Duke considered to be outrageous, and said as much. It was thereupon withdrawn, but Latimer was found guilty on the other charges and the Duke, biting his lips and avoiding the convicted peer's frightened foxy eyes, made no further effort to save him.

The Commons exulted openly: they had for the first time in history succeeded in impeaching a minister of the crown!

John had been to Mass that morning and mere prayed that he might be guided by justice in the coming trials and that he might be given strength to conciliate the people as his brother had implored him to do. Revolt, civil war - like the evil smell of brimstone in plague time - pervaded the air of the Painted Chamber, indeed the air of all England. The Prince thought compromise the best way of clearing it, and he might be right.

The indictment of Lord Latimer had been expected, the identity of their next quarry had not.

A collective gasp rose from the lords' benches as de la Mare called, "Lord Neville of Raby!"

"What's this!" cried Neville, jumping to his feet and turning purple. His fierce little boar's eyes glared at the Speaker and then at his hereditary enemy, Percy of Northumberland. He strode down the hall towards the Commons, his great chest swelling. He shook his fist shouting, "How dare you churls, ribauds, scum - to question me, a premier peer of the realm!"

Some eighty pairs of eyes stared back at him defiantly. He swivelled and charged through the centre of the Chamber past the four woolsacks up to the dais. "You cannot permit this monstrous act, Your Grace!"

The Duke's nostrils indented and he breathed sharply. For Latimer he was not responsible, but Neville was his own retainer who had served him for years. A rough, violent man of war, like the other Border lords, yet ever loyal to Lancasters. The Duke hesitated, men he said quietly, "It seems that we must hear, my Lord Neville, what they would say."

The Speaker bowed and launched forth at once, raising his voice over Neville's uproarious objections. The Commons' charges of illicit commissions were trivial, a matter of two marks a sack in some wool transaction which Neville furiously denied, but he could not sustain his innocence. The next accusation, that four years before he had produced an insufficient number of men to serve in Brittany and then allowed these men to conduct themselves licentiously while awaiting shipment, Neville contemptuously refused to answer at all.

Commons, considering that the charges were proved, requested that he be removed from all his offices, and heavily fined.

This is ridiculous, thought John, 'tis only to insult me that they attack Neville. Though mere had been slight dishonesty proved, what man among the Commons, what man among the twelve turncoat lords had not done as much? But he tightened his jaw and held his peace. He waited for the next accusation in grim suspense and was relieved at the object of their final and most virulent attack - Alice Perrers.

There was truth in what they said of Alice: that she was rapacious, venal and a wretched influence on the King; that she bribed judges, forged signatures, and helped herself to crown funds and jewels. Moreover, they said, it had been discovered that she was married and thus wallowing in flagrant adultery and that her hold on the King could only be the result of witchcraft. A Dominican friar had given her magic rings which had produced enslavement.

He equably acceded to the Commons' wish and had Alice summoned to the bar. She came before them soberly dressed and demure, her little cat face hidden by a veil, her head meekly bowed, which did not prevent her from casting voluptuous, imploring glances sideways at the Duke.

He had her sentence softened to banishment from court, and they forced her to swear on pain of excommunication and forfeiture of all her property that she would never again go near the King. Then they appointed two sergeants-at-arms to go with her and see that she obeyed.

"And now, by God," said Lord de la Pole to the Duke, on the day that Commons finished dealing with Alice, "I think we're out of this stew. See that sharp-toothed young de la Mare's jaded at last, there's no more bite in him. I was proud of you, my lord. 'Twas no easy thing to let them override your inmost wishes and your loyalty. And yet I think it had to be, some of their claims were just and it may be wise to sacrifice royal prerogative at times, if it gain the love of the people."

"Ay, so my brother of Wales thinks," said John, smiling into the bluff, affectionate eyes of the older man. "But by Christ's sweet blood, now they must be contented. Is it too much to hope they may even be content with me?" He looked at his friend with a sudden wistfulness.

Before the baron could answer they were interrupted by a messenger who rushed into the Painted Chamber and, throwing himself to his knees before the Duke, panted out urgent words. The Duke shook his head with a look of deep sorrow. He rose and held his hand out to still the hubbub. "Lords and Commoners all," he said, "we must adjourn. The Princess of Wales has sent from Kennington. This time there is no hope of his rallying."

Edward of Woodstock, the Black Prince, died on Trinity Sunday, the eighth of June in his forty-sixth year. The King his father, and the Duke his brother, knelt by the bedside, and to those two he confided the care of his wife, Joan, and the nine-year-old Richard. The King and Duke kissed the Bible held out to them by the Bishop of Bangor to seal their oath.

Then the old King beat his breast and fell into a pitiable childish weeping, until the Princess Joan led him away.

The Duke and the bishop remained with the Prince until the end came, when John leaned down and kissed the brow which had been contorted with pain and was now suddenly at peace. As the Bishop of Bangor folded the gnarled warrior hands across the still breast, John left the bedside and walked into the antechamber, where the old King whimpered in his chair and stared with frightened eyes at the crucifix that was fastened to the wall.

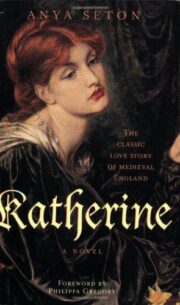

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.