But John had commanded him to speak, knowing that he would be better armed to protect the crown for the coming fight in Parliament if he knew all their preposterous weapons.

"Some cock-and-bull tale that Your Grace is a changeling, not of royal birth."

"Bah! How feeble" - John had laughed. "Their other inventions are better. What more do they say of this? What particulars?"

" 'Tis all I heard," said Raulin, "no von beliefs it."

John had shrugged and spoken of something else, but in his stomach it was as though a cannon ball had gutted him, and his whole body trembled inwardly like that of the child who had first heard the word "changeling" nearly thirty years ago. Beneath his intercourse with others, beneath his joy at seeing Katherine, he had been trying to turn cool logic on this shameful fear. The King of Castile and Leon, the Duke of Lancaster, the most powerful man in England, to be overwhelmed by a vague whisper, to feel like a whimpering babe - cowering in terror of treachery, and injustice and loss. Last night he had dreamed of Isolda, and that he, a child again, looked up to her for comfort; but her grey eyes held naught but contempt and she sneered at him saying, "And did you believe me, my stupid lordling, when I said Pieter had lied? He did not lie, and you are hollow, empty as a blown egg, no royal meat within you."

"My dearest, what is it?" cried Katherine again, for the muscle of his arm jerked and the hand that had lain along her thigh clenched into a fist.

"Nothing, Katrine, nothing," he cried, "except I shall deal with my enemies! The hellish monks and the ribauds of London town - I'll crush them till they crawl on their bellies, snivelling for mercy; and I'll show none!"

She was frightened, for she had never heard him like this, and she said timidly, "But great men such as you, my lord, always have enemies and ever you have been above them - just and strong."

"Just and strong," he repeated with a bitter laugh. " 'Tis not that they call me - ay - do you know what they think, Katrine? They think I have no loyalty to my father and my brother. They think I plot to seize the English throne. The curse of God be on the fools!"

He shut his mouth, scowling into the darkness. His father and his brother - the idols of the nation, both feeble, ailing, moribund and at loggerheads just now. The Prince of Wales, frantic to conserve the kingdom for his son, little Richard, and to soothe the dangerous unrest of the English people, had called this Parliament and caused it to be subtly known that he would back the Commons in its attack upon the corruption around the doddering King. The Prince from his sick-bed looked to John for support in this. The King too, caring only to giggle and toy with Alice Perrers, yet looked with childish faith to John to spare him discomfort and uphold the divine rights of the crown. Mediator, scapegoat! John thought violently. I bow my head to obey them both, to fight for what they each demand, and hear myself called traitor for my pains.

Yet this injustice but bred a clean contemptuous anger, not like that other squirming shameful fear which he now subdued again, helped by the unquestioning love of the woman beside him. What use to fear a vague slander which might well have been a chance shot and a not uncommon one in history, when fears were felt for the rightful succession? Doubtless, as Raulin said, few knew of it and none believed it.

He breathed deeply and turning to Katherine, kissed her. "By Saint John, my love," he said in the light tender voice he kept for her alone, "I've been tilting with a phantom. I'll cease my folly."

She understood nothing of this, except that his dark mood had passed and that in her he found comfort.

But while he slept at last in her arms, it was as though his distress had passed to her and she suffered that there was so much of his life she did not know.

CHAPTER XVII

St. George's Day was a happy one at Kenilworth. The Duke was his gayest, his most charming.

For two days and two more nights John and Katherine knew poignant joy, poignant in that it must be so brief; then on Friday morning the horses were again assembled by the keep, and the heavy carts and wagons lined up below in the Base Court, while varlets scurried to them from the castle bearing travelling coffers.

At six, Lancaster Herald blew a long plaintive blast of farewell. Katherine, standing on the stairs, bade them all Godspeed - to little Henry of Bolingbroke, who, of course, returned to London with his father, to Geoffrey on his bony grey gelding, to the Lords Neville and de la Pole on their brass-harnessed destriers; to Lord Latimer, whose long vulpine nose was red from the chill morning wind as he stood beside his lady's litter. And to John Wyclif, the austere priest, who alone of this company had held himself apart from the merrymaking. Not discourteously, but as one whose thoughts were elsewhere, and whose interest lay only in moments of earnest converse with the Duke.

They had all mounted before the Duke turned to Katherine, who waited with bowed head, holding out to him the gold stirrup cup.

"God keep you, my love," he said very low, taking the cup and drinking deep of the honied mead. "It'll not be long this time, I swear it by the Blessed Virgin," he added in answer to the tears in her eyes. "You know I ache for you when we're apart."

She turned away and said, "Do you stop now at Hertford?" This question had been gnawing at her heart, and she had not dared voice it.

"Nay, my Katrine," he said gently, "I go straight to London to be ready for Parliament, you know that. You may be sure the Queen Costanza's no more eager for my company than I for hers."

She did not know whether he lied to her, out of kindness, but her heart jumped at the cold way he spoke of his Duchess, and she looked at him in gratitude, yet lifting her chin proudly, for she would not be a dog fawning after a bone for all the watching meinie to see.

He kissed her quick and hard on the mouth, then, mounting Palamon, cantered through the arch.

On the twenty-ninth of April, shortly before the hour of Tierce, as the Abbey bells were ringing, the King opened Parliament in the Painted Chamber at Westminster Palace. Then he seated himself on his canopied throne, while his sons disposed themselves according to rank on a lower level of the dais. But the Prince of Wales lay on a couch, half concealed by his standard-bearer and a kneeling body squire. The Prince was a shocking sight. His belly was swollen with the dropsy as his mother's had been, his skin like clay and scabrous with running sores. Only his sunken eyes at times shone with their old fierce vitality, as he turned them towards the King, or to his brother of Lancaster, or out past the bishops and lords to the crowd of tense murmuring commoners at the far end of the long hall.

King Edward held himself erect at first and gazed at his Parliament with something of the calm dignity of his earlier years; but gradually he drooped and shrank into his purple robes of state. His palsied fingers slipped off the sceptre, and his face grew wrinkled and mournful like a tired old hound's. Except when he glanced towards the newel staircase in the corner behind the dais and saw the painted arras quiver. Then he brightened, and tittered behind his hand, knowing that Alice was hidden there on the turn of the stair.

The Duke of Lancaster sat on a throne too, one emblazoned with the castle and lion, for was he not - however far from his kingdom - the rightful ruler of Castile and Leon? Next sat Edmund of Langley, his flaxen head nodding with amiable vagueness to friends here and there amongst the lords, while he cleaned his fingernails with a little gold knife.

On the King's left his youngest son, Thomas of Woodstock, dark and squat as his Flemish ancestors, scowled at the wall where there was painted a blood-dripping scene from the Wars of the Maccabees. Thomas was not yet of age and never consulted by his father or brothers. He resented this but bided his time in wenching and gaming, and quarrelling with his wealthy young wife, Eleanor de Bohun.

The morning was indeed dull. It opened with the expected speech by Knyvett, the chancellor, who droned on for three hours while exhorting the Houses to be diligent in granting the kingdom a new subsidy; money urgently needed, said the chancellor, for the peace of the realm, defence against possible invasion and resumption of the war in France, also - here he glanced at the Duke - in Castile.

As Parliament was invariably called for like reason, the speech held no surprises and those on the royal dais and the lords on their cushioned benches muffled yawns.

The Commons were ominously quiet. At the conclusion they asked permission to retire to the Abbey chapter house for consultation. The King, who had been drowsing, sat up and quavered happily, "So it's all settled. I knew there'd be no trouble. The people love me and do my bidding." He rose and glanced towards the arras. He wanted his dinner, which would be served him in a privy chamber with Alice, and he wandered towards the stair. His two elder sons looked at each other, John in response to a gesture walked over to his brother's couch.

"Let him go," whispered the Prince. "He'll not be needed now." He fell back on the cushions, gasping. His squire mopped his temples with spirits of wine and after a moment the

Prince spoke again. "Nor am I needed. Christ's blood, that I should come to this - useless, stinking mass of corruption! John, I must trust you. I know your loyalty - whatever they say. Conciliate them - listen to them. Hold this kingdom together for my son!" Tears suddenly spurted down his cheeks and a convulsion shook his body.

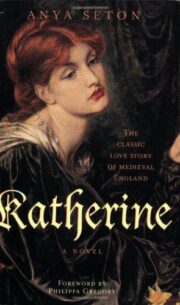

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.