Hugh's lodgings were two rooms over a wine-shop in an alley behind the cathedral. Nirac duly guided Katherine through the town from the pier, while a small donkey laden with her two travelling chests ambled with them. She had managed to avoid the Duke entirely, even taking it upon herself to tell Nirac of the Duke's permission and order Nirac to accompany her.

This order Nirac received with an enigmatic shrug and smile, "Comme vous voulez, ma belle dame" and she thought that the faithful, amusing little Gascon whom she had known so well in England had somehow changed here in his native land. She chided herself for thinking him suddenly sinister and secret, like the twilit town that turned blank walls to the street and hid its true life from passers-by.

It was not until they mounted the littered stone stairs above the wine-shop that Katherine thought of the angry treatment Hugh had shown to Nirac long ago at Kettlethorpe and wondered if the Gascon still resented it, but then she thought that if he did it would not matter; stronger than any other thing in life for Nirac was his adoration of the Duke, and that feeling would check all others.

"Are you sure this is it?" she asked dubiously as they stood on a cramped landing and she knocked at a rough plank door. There was no sound from within.

"La cabaretiere said so, madame," answered Nirac who had inquired from the shopkeeper.

Katherine knocked again, then pushed open the sagging door, calling, "Hugh."

He lay on a rough narrow bed and had been dozing. The single shutter was closed against the heat, and in the dim light he blinked at his wife, who lit the doorway like a flame. Then he struggled to his elbow and said, uncertainly, "Is it really you, Katherine? But it's early - Ellis left to fetch you but a short time ago - we heard the ship was sighted in the river. Who's that behind you, is it Ellis?"

"No, Hugh," she said gently, going to the bed and taking his hand, "it's Nirac, the Duke's messenger. I hurried straight to you and have missed Ellis."

His hand clung to hers, it was hot and dry. His unshaven face was haggard between the matted wisps of his crinkled hair, and in his voice she had heard the querulous note of ill health. On a stool by the head of the bed there was a pile of torn linen strips, a bleeding basin and a small clay cup. Flies buzzed in the stuffy sour room, the dingy hempen sheet on which Hugh lay was wadded into lumps. She bent over and kissed him quickly on the cheek. "Ah, my dear, 'tis well I've come to nurse you. The Duke said you were better, are you?" She glanced at the bandaged leg, which was propped on a straw pillow.

"For sure 'e's better!" cried Nirac heartily, coming forward to the bed and bowing. " 'Is Grace's own leech 'as cared for 'im, an' now 'e 'as the best medicine in the world!" He smiled at Katherine, his bright black eyes were merry and charming, and she wondered what had made them seem sinister before.

Hugh said, "Oh, it's you, you meaching cockscomb. I'd forgot all about you." His dull gaze wandered from the Gascon to Katherine. "Ay, I'm better, the wound's near done festering. I'd be up now save for the griping in my bowels, it weakens me."

"Alack!" she said, " 'tis the flux again? But 'twill pass - you've got over it before."

He nodded, "Ay." He made effort to pull himself from the self-centred lethargy of his illness, yet in truth her beauty daunted him; and though he had much wanted her to come, now he felt the old discouragement and humiliation which always sought relief in anger.

"Now you are here," he said crossly, "I trust you're not too fine a lady to fetch us up some supper and wine from the woman's kitchen down below. Or has the Duke's appointment turned your head?"

Nirac made a faint hissing sound through his teeth, but she did not hear it as she answered, "I'm here to care for you, Hugh. Come, don't speak to me like that," she said smiling. "Don't you long for news of home - of our children?"

"I leave now, madame," said Nirac softly, and he added in swift French, "I wish you joy of your reunion." He was gone before she could thank him for his long care of her on the journey.

Through the rest of the day Katherine tended her husband. She took off her fine green gown and put on a thin russet kersey which she wore for everyday at Kettlethorpe; in this she tidied and cleaned the two bare little rooms. She made Hugh's bed, washed him and re-bound his leg, hiding her revulsion at the look of his wound, which was puffed high with proud flesh and oozing a trickle of yellow pus. But Hugh said it had much improved, and Ellis, when he returned from his fruitless errand to the ship, also agreed.

Gradually Hugh grew gentler, as the first shock of strangeness wore away. They slipped back into the groove inevitably worn by their five years of marriage. After they had supped and were more at ease and glowing from the delicious Gascon wine, Ellis sat by the window with his back turned to them, tinkering with some buckle on his master's gear, and Katherine curled up on the bed chattering of the babies - how lovely little Blanchette had grown and that she could sing three songs - here Hugh smiled proudly, seeming more interested than at the news that Tom could talk plainly and sit a horse alone and was near as big as his sister.

Katherine told many items of home news, particularly that the new flocks on the demesne farm were flourishing and that the Lincoln merchants, the Suttons, had been helpful with advice. She also told Hugh about the birth of Philippa's baby, proudly adding that she had done most of the midwifery herself, with Parson's Molly to assist. "But Philippa had an easy time - the babe popped into the world like a greased pig from a poke," she laughed, "not like the struggle I had to birth Blanchette."

"Ay, but you're no more like your sister than Arab filly is to plough horse, my Katherine," said Hugh gruffly, not looking at her but fumbling for her hand. He pulled her down so that her bright face rested against his coarse woolly beard: She held herself tight so as not to draw back, and thought of the three violent and unhappy nights in which he had once more claimed her during their last brief time together at Kettlethorpe when she came home from the Savoy and before he left to join Sir Robert Knolles.

Hugh thought of those nights too, and cursed the physical debility that once more unmanned him, knowing that without the vigour of drunken haste, a paralysing doubt would set in - and fear, and then he would hate her and the lovely body which he well knew he had never truly possessed.

"I thought I had got you with child, before I left," he said, releasing her suddenly.

She sat up with an imperceptible sigh of relief. "Nay," she said lightly. "It didn't happen, doubtless because 'twas, the dark of the moon then. Hugh, tell me of the fighting you've been through, tell me how you got this" - she touched the bandaged leg. "Here I prate on of silly humdrum things at Kettlethorpe while you've done many a dangerous deed of arms."

She led him on to talk of the one subject which he understood, where he felt himself always sure, and under her admiring questions he expanded, words came to him more easily, his scowl vanished, and when he started to describe a hand-to-hand encounter with a Poitevin knight, in which the latter had cravenly cried for mercy, he actually laughed.

It was thus that Brother William Appleton found them when he pushed the door open and padded in on his bare feet. "Deo gratias!" cried the Grey Friar, standing at the foot of the bed and surveying his patient with kindly surprise. "Here is betterment indeed! Truly a wife is God's gift. Benedicite, my Lady Swynford." He placed his hand on her head. "How was the voyage?" He dropped his sack of drugs and instruments on the floor and smiled at Katherine.

"We had a great storm and I was much afraid," she said, hastening to pour the friar a cup of wine, "but our Blessed Lady and the saints vouchsafed a miracle and we were saved. It was a most wondrous and humbling thing." Her voice trembled, and Brother William glanced at her keenly, thinking that though she seemed made for the pleasures of the flesh, there yet was a sense of spiritual striving about her, and a healthiness of mind and body which pleased him who spent so much of his time with the sick. "Ay, it is a humbling thing when Heaven's mercy shields us from danger" - he nodded his long cadaverous head - "and we may be sure God sends us every chance for salvation - how do you find your husband?"

"Most grateful to you, Sir Friar, he says you saved his leg and maybe his life."

"Well, well - I've some skill but 'tis not all my doing. His stars were propitious." As he spoke the-friar deftly unbound Hugh's leg, and scooping a green ointment from a little pot plastered the wound. " 'Tis made of pounded watercress," he explained to Katherine, who exclaimed at the colour. "A balm the wild Basques use in their mountains, and ignorant as they are - barely Christians - they know much of simples. I've healed many a wound on the Duke's men-at-arms with this."

"How soon do you think I can get about, Brother?" asked Hugh through clenched teeth as the friar probed and pulled back the proud flesh.

"You can hobble a bit now, since it seems your dysentery's lessening. Did you take all the bowel-binder I left you?" He peered into the clay cup on the stool and shook his head. "Lady, you must see that he takes this each time before he eats. Camphorated poppy juice alone will heal the flux."

"I'll see that he takes it. Sir Friar," she said smiling, and held the cup for him to fill it with a black mixture.

"We must have you strong and able to attend on the Duke's wedding, Sir Hugh," said Brother William, fishing a rusty lancet from the bottom of his sack and motioning to Katherine to hold the basin for the daily bleeding.

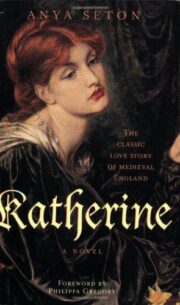

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.