"He," said de la Pole, frowning in the direction of the Avalon Chamber, "has not even reported to the King on our campaign in Picardy!"

"Nothing to report, I hear," growled Neville, "since you never joined in battle - body of Christ, why didn't you force the French bastards to fight?" He glared at de la Pole from beneath his bushy grizzled eyebrows. A harsh North Country man was the great Lord of Raby and never one to mince words.

De la Pole's ruddy face darkened, but he answered temperately. "How could we, since they hid from us? We did what might be, we burned the country from Calais to Boulogne; but ill luck hounded us, and the plague there too." He sighed, thinking of the many plague deaths in camp. "But what's our next move to be? The Prince of Wales is sore beset in Aquitaine, Edmund piddles away his forces in the Dordogne, that hot fool of a young Pembroke will listen to nobody and holds himself a better soldier than Chandos - we must plan a new attack - yet my Lord Duke sits in there moping alone."

Lord Neville blew his beaked nose loudly with his fingers and wiped them on his miniver-lined sleeve. "Aye," he said angrily," 'tis not of the land I wish to speak to him, 'tis of the disposition of our ships." Neville had just been appointed Admiral of the Fleet and as a man of fifty and an arrogant one, it irked him to wait on the decisions of a man of twenty-nine, though he was his feudal overlord. There was a stir across the room, a yeoman held open the great oak and wrought-iron door. Two friars padded in.

"Ah, now we have the godly faction represented," said de la Pole dryly. "We'll see how they fare."

The two friars were as unlike as a grey heron and a plump hen. Brother William Appleton, the lean Franciscan physician, towered a head above Brother Walter Dysse, the Carmelite, whose snowy cope was woven of the softest Norfolk worsted and belled out to show glimpses of an elegant tunic, and a gold and crystal rosary dangling from a paunch as neat and round as a melon. And while the Franciscan grey friar was shod only by his own soles, the Carmelite had soft kidskin shoes and wore hose of lamb's wool.

"Nay, brethren," said the young body squire to them, flushing, for he was still unused to the new importance the Duke's behaviour had thrust upon him. "His Grace vill not see you either. He says his body and soul must shift for themselves since he cares naught about them."

"Christus misereatur!" said Brother Walter lisping slightly as he palmed his plump white hands. "Sweet Jesu, but that is a melancholy message."

"He cannot help himself," said the physician, thoughtfully, "his horoscope shows him much afflicted by Saturn. Yet, for that black bile from which he suffers he should be bled, and I have other remedies which might help, could I but try them."

"And how long will His Grace be ruled by Saturn?" asked Baron de la Pole walking over to the Grey Friar. "By God, I hope not long."

"The aspects are somewhat unclear, and yet it seems that soon Venus will ascend and mitigate the baleful Saturn," answered Brother William carefully.

"Venus forsooth!" cried the Baron. "Don't prate to me of Venus, Sir Friar - it's Mars that we need! Mars! - look now here come two more black crows!" he added as the great door again swung open: Court mourning for the Queen and the Duchess would last until Christmas and had peopled the palaces with black, which depressed de la Pole, who was fond of scarlet. The two new-comers were not Lancastrians however, and de la Pole drew close to Lord Neville, who still fidgeted by the window. Both men stiffened and watched the new-comers warily. These two noble young sprigs, the Earl of March and Richard Fitz Alan, heir of Arundel, were known to hold little love for the Duke.

Edmund Mortimer, the Earl of March, was great-grandson to the Roger Mortimer who had been Queen Isabella's paramour, but he had no likeness to that lusty man. This Mortimer was a weedy stripling of eighteen with pimples thick upon his beardless face. Insignificant as a stable-boy, a stranger might have thought of him, except for his pale eyes, which had a cold steady gaze; but no one in the Presence Chamber thought him insignificant. He was the ranking earl, he owned vast possessions in the Welsh Marches and in Ireland, and he had recently wed young Philippa, the only child of Duke Lionel of Clarence, and thus become grandson to the King.

"I'm here," he announced in a high "grating voice, "to see Lancaster. I have a message for him." He glanced at the friars, then at the two barons. His companion, Fitz Alan, nodded agreement and spread his stubby hands to the fire.

"No doubt you do," said de la Pole, "but he's not to be disturbed."

"By God's bones, indeed he's not!" growled Lord Neville. Whatever bickering they might indulge in amongst themselves they were at one against outsiders.

"I come," said Lord March imperturbably, "from the King. He summons the Duke to Westminster at once, for conference. He's to accompany me now. Kindly have me announced." March's spotty little face was smug, and the two barons were silenced. No one might disobey a summons from the King, not even a favourite son, but de la Pole thought that a more agreeable messenger might have been chosen. No doubt the choice was Alice Perrers' doing. She blew now hot now cold on this courtier or the other as her subtle mind conceived it to her advantage, and the King did as she wished.

Raulin departed on this new errand to the Avalon Chamber, and the company settled to wait for his return. The little earl hunched himself in a gilded chair before the fire and shivered, for his skinny body was always chilly. He stared enviously at two huge Venetian candlesticks which flanked the fireplace. They discontented him with a pair he had recently ordered for himself, as the Savoy discontented him with his own city mansion, and that knowledge that, while he owned ten castles, John of Gaunt had more than thirty. His thoughts turned to the heir his countess was expecting. There at least he bettered the Duke. This babe, whatever it was, stood nearer to the English throne than Lancaster or any get of his.

"That churlish squire takes long to return," he said to Fitz Alan who was munching a handful of raisins and spitting the seeds out at an andiron. "That Fleming - why must Lancaster ever show favour to foreigners!" March reached for a raisin, then thought better of it. Two of his teeth were rotting and sweetness hurt them. "By Saint Edmund!" he began peevishly, "the Duke forgets my rank, this is outrageous -" He stopped, for Raulin returned slowly through the door and came up to him, bowing.

The squire fixed his eyes on a tapestry behind the earl's head and said without inflexion, "My lord, His Grace sends his love and duty to the King and prays His Majesty to bear with him. He cannot come now but vill anon."

De la Pole watching from the window could not hold back a chuckle at the little earl's expression. March got off the chair and drew himself as high as he could. "D'you mean to tell me it took all this time to produce this insolent message!" he shrilled at the squire, who closed his lips and stared stolidly towards the wall. It had taken no time at all for the Duke to give that message, the time had been taken by another matter which caused Raulin much hidden amazement.

"Well, my lord," cried de la Pole cheerfully, "you've had your answer!" His own discontent with Lancaster had melted into pride. The Duke was afraid of nothing, not even his father's famous Plantagenet temper, and de la Pole gave thanks that he owed his homage to the Duke instead of to this pimpled bantling, or any other overlord.

One by one they departed until the Presence Chamber was emptied of all but the squire. Raulin waited until there was no one on the stairs, then sped out into the courtyard and, obeying the Duke's orders, made for the Beaufort Tower.

The porter told him that Lady Swynford was not within. Her mare had been saddled and brought, and she had left some time ago.

"Did you hear naught of vere she might've gone?" pursued Raulin who knew nothing about the woman he was seeking and whose competent Flemish brain was mystified by the dark urgency his master had shown.

"I might of," the porter paused and picked his nose thoughtfully, "were't to my interest."

Raulin opened his purse and held out a quarter-noble. The porter bit it and said, "My Lady Swynford did ask the way to Billingsgate, summat abaht fishmongers it were - fishmongers wi' a fishery French name - Poissoner - Pechoner - she wanted to see."

Raulin, finding that the porter could give no other information, set off for the City on what seemed an unlikely quest. But the Duke had forbidden him to return without this Lady Swynford. He rode to town and down Thames Street towards the Bridge and began to make dogged inquiry.

Katherine had spent the last days in growing dejection. Her grief and horror had worn themselves out at last and she had stood amongst the hordes of mourners in St. Paul's and felt only sadness. Since then, she had been planning how to get home, but there were material difficulties. She had not enough money for the journey, nor did she dare set off without escort. The wisest thing would be to get a message to Hugh that he might send Ellis for her. But that would take time. In that vast Savoy Palace she felt as lost and forgotten as in a wilderness. The ducal children had been taken with their household to the country air of Hertford Castle, and most of the Bolingbroke people had dispersed after the funeral.

The decision to go to Billingsgate and seek Hawise had been impulsive, and once she had thought of it, she lost no time and set off in a chill and windy drizzle.

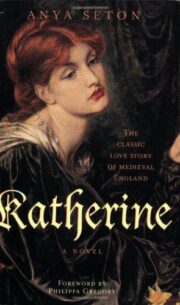

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.