"No," she said, though her heart beat slow and heavy. "I cannot. I'm going in. Belike I'm safe from the contagion, Philippa said so, but whether or no, I must go in to the Duchess."

"You're mad, lady - Sir Hugh would kill me if I let you go -

She saw that he meant to drag her off by force, his hand clenched on her arm so she near overbalanced in the saddle. Deliberately she called on anger.

"How dare you touch me, knave!" she said, low and clear. "How dare you disobey me?" And with her free hand she slapped him hard across the face.

Ellis gasped. His hand fell off her arm. His mind floundered in a coil of fear and uncertainty.

She saw this and in the same clear voice said, "You need not enter the castle with me, I release you from your duty, but this you must do. Ride fast to the abbey at Revesby, it's the nearest as I remember. Bring back a monk, at once! In the name of the Trinity, Ellis - -go!" Such force did she put in her voice, such command in the look she gave him, that he bowed his head. "The road to Revesby lies that way," she said pointing, "then to the west." He tautened the reins and spurred his horse.

"Guard! Ho, guard!" Katherine called turning to the castle. The helmet showed again in the window. "Lower the bridge and let me in!"

"Not I, mistress," again the man let loose a gust of laughter. "I'll not budge." His tone changed as he pushed closer to the window. "What, little maid, and do you lust to join our sports in here? By God's bones, the Black Death holds merry dances! The postern gate is open since 'tis through there the castle varlets fled." He leered down at her.

Katherine guided Doucette along the dry moat past the south tower to a footbridge that led across to the postern. She dismounted and tied the mare loosely to a hazel bush that it might graze. She unbuckled her saddle pack and hoisting it in her arms crossed the footbridge. Between the batterns on the low oak door another red cross was painted and beneath it in straggling letters, "Lord have mercy on us."

She went through the unlocked door into the bailey. On the flagstones near the well another plague fire burned. An old man in soot-tarnished blue and grey livery threw handfuls of yellow sulphur on the smouldering logs. He raised his shaggy head and looked at her dully. Two other figures moved in the bailey. They were hooded and masked in black cloth and they held shovels in their hands. The flagstones had been lifted from a section of the western court near the barracks and she saw that a long ditch had been dug into the earth. Beside the ditch there stood a high-mounded bumpy pile covered by bloodstained canvas, and the stench from this pile mingled with the fumes from the fire.

Katherine tried to turn her eyes away from the mounded pile but she could not. One man seized a little hand-bell and, jingling it, muttered behind his mask. He put the bell on the ground, and the two hooded figures silently dragged a limp thing with long black hair from out the pile and heaved it into the ditch, where one blue-spotted wrist and hand protruded for a moment like a monstrous eagle's claw, then slowly sank from sight.

Katherine dropped the bag she carried. She ran stumbling towards the private rooms at the far end of the bailey. She reached the foot of the stone staircase that led up to the Duchess's apartments. Here it was that she had stood laughing at the mummers' antics with the two little girls in that Christmastime three years ago. She looked back into the smoke-filled silent courtyard and saw the hooded figures fumble again beneath the canvas on the mound.

Her stomach heaved, while bitter fluid gushed up into her mouth. She spat it out and, turning, began to mount the worn stone steps. As she rounded the first spiral the hush that held the castle was broken by the sudden tolling of a bell. Muffled though it was by the stone walls around her, she knew it for the great chapel bell and she clung to the embroidered velvet handrail while she counted the slow strokes. Twelve of them before the pause - a child then, this time - somewhere in the castle and dimly through the knell she heard a long far-off wailing.

At once much nearer sounds broke out from above her, a wild cacophony of voices and the shrilling of a bagpipe. She listened amazed; in the discordant sounds she recognised the tune of a ribald song, "Pourquoi me bat mon mart?" that Nirac had taught her, and many voices were bawling it out to the squealing of the pipes and the clashing of cymbals.

As Katherine mounted slowly the noise grew more raucous, for it came from the large anteroom outside the Duchess's solar, and the door was ajar. There were a dozen half-naked people in the room, all of them in frantic motion, dancing. Nobody noticed Katherine, who stood transfixed in the doorway. Despite the fog heat, a fire was blazing on the hearth and the painted wall-hangings were illuminated by a score of candles. On the table, which had been pushed to the wall, there was the carcass of a roast peacock, a haunch of venison and a huge cask of wine with the cock but half shut; a purple stream splashed down on the floor rushes which had been strewn with thyme, lavender and wilting roses. To the falcon-perch beside the fireplace, a human skull had been tied so that it dangled from the eye-sockets and twisted slowly from side to side as though it watched the company who danced around and around upon the rushes. They jerked their arms and kicked their legs. When the minstrel who held the cymbals clashed them together, a man and a woman would grab each other convulsively and, kissing, work their bodies back and forth while the rest jigged and whirled and called out obscene taunts.

Katherine, held viced as in a nightmare, recognised some of these people, though their faces were crimson and slack with drunkenness. There was Dame Pernelle Swyllington, the stout matron who had protested against Katherine's presence in the Lancaster loge at the tournament at Windsor. Her bodice was torn open so that her great breasts hung bare, and the cauls that held her grizzled hair had twisted loose and bumped upon her shoulders as she danced. There was Audrey, the Duchess's tiring-woman, dressed in a wine-stained white velvet gown, trimmed with ermine, the skirt held bunched up around her waist, though yet she tripped and stumbled on it. Her broad peasant face was wild as a bacchante's beneath one of the Duchess's jewelled fillets. Audrey held Pier Roos by the hand and when the cymbals crashed, she flung herself against his chest, slavering. The young squire wore nothing but a shirt and was drunk as the rest, his pleasant freckled face drawn down into a goatish mask, his eyes narrow and glittering. A kitchen scullion danced with them, and a small pretty young woman - a lady, by her dress - who giggled, and hiccuped and let any of the men fumble her who wished; Piers, or the scullion, or the minstrels - or Simon Simeon, the steward of Bolingbroke Castle.

It was the sight of this old man, his long beard tied up with a red ribbon, his portly dignity lost in lewd capers, a garland of twined hollyhocks askew on his bald head, that shocked Katherine from her daze.

"Christ and His Blessed Mother pardon you all," she cried. "Have you gone mad - poor wights?" A sob clotted in her throat, and she sank down on to a littered bench, staring at them woefully.

At first they did not hear her; but the piper paused for breath and the steward, turning to catch up a mazer full of wine, saw her and blinked foolishly, passing his hand before his bleared eyes.

"Sir Steward," she cried out to him, "where is my Lady Blanche?" Her despairing voice shot through them like an arrow. They ceased dancing and drew back, huddling like sheep menaced by sudden danger. Dame Pernelle clenched her hands across her naked breasts and cried thickly, "Who are you, woman? Leave us - begone." Piers' arm dropped from Audrey's waist and he shouted, "But 'tis Lady Swynford - by the devil's tail! I've longed for this! Come dance with me, my pretty one, my burde, my winsome leman-" His nostrils flared on a great lustful breath, he shoved Audrey to one side and would have grabbed at Katherine, but the old steward stepped between and held his shaking arm out for a barrier.

"Where is the Duchess?" repeated Katherine, unheeding of Piers.

"In there," said the steward slowly. He pointed to the solar. "She bade us leave her - while we wait our turn."

"She's dead then," Katherine whispered.

The steward bowed his head and through mumbling lips he said, "We know not."

Katherine jumped from the bench and ran past them to the solar door. They watched her dumbly. Piers drew back against the others. They made no sound as she went through the door but when it closed behind her a woman's voice cried out, "Give me the wine!", the pipes shrilled and the cymbals crashed anew.

In the great solar it was dim and quiet. Two huge candles burned on either side of the vast square bed that was hung with azure satin. The Duchess lay there on white samite pillows. Her eyes were closed, but her body twitched, her breath was like the panting of a dog. Her arms were closed on her chest below a crucifix, the white flesh mottled from the shoulder to the elbow with livid spots. A trickle of black blood oozed from the corner of her mouth and ran on to her outspread golden hair.

As Katherine gazed down, shuddering, the purple lips drew back and murmured, "Water -" The girl poured some into a cup and the Duchess swallowed, then opened her eyes. She did not know the face that bent over her, and she whispered, "Where's Father Anselm? Tell him to come - I haven't long - nay, Father Anselm's dead, he died the first-" Her voice trailed into incoherent muttering.

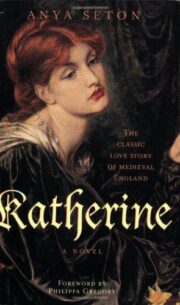

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.