With little Tom it was different. Katherine looked down at the withe cradle where her son slept. He had been born in September on St. Matthew's Day nearly a year ago. He had given no trouble then, and he gave none now. He was a stolid child who seldom smiled and never gurgled or shrieked as Blanchette did. He had hemp-coloured crinkled hair and was in fact remarkably like his father.

Katherine sighed when she thought of Hugh. This morning when he rose at dawn to hunt the red deer in the forest, his bowels had griped and run with bloody flux again, and he had been so weakened after an hour at the privy pit behind the dovecote that even with Ellis's help he had scarce been able to mount his horse. This dysentery that Hugh had brought back from Castile often seemed cured and yet each time returned, despite Katherine's nursing and all the remedies suggested by Parson's Molly. They had tried garlic and ram's gall clysters, they had bled Hugh regularly, sprinkled his belly with holy water, and even called in the leech monk from St. Leonard's priory in Torksey. This monk fed Hugh a potion made of powdered toadstone, bade the ailment begone in the name of the Trinity and gave him a paper to wear above his navel on which was written, "Emmanuel, Veronica," but still the seizures and the flux came back at intervals, and Hugh suffered grimly.

The mourning bell, after a pause, clanged out again the first of fifty-six long tollings, one for each year of the Queen's life. Katherine recited a prayer, then settled herself more comfortably on the straw and leaned her head against the gatehouse wall. Blanchette had gone to sleep and Katherine eased the child down beside her. Flies buzzed lazily over the stinking dung pile near the cow-byre, where several chickens scratched for seed, but otherwise the courtyard was quiet, its usual activities suspended out of deference to the Queen. The afternoon grew warmer and Katherine longed for a drink, but she feared to disturb Blanchette and in any case was too drowsy to walk across the court to the well, and she would not tap the keg of ale they kept in the undercroft beneath the solar, for they must eke out the little they had left. God alone knew when they could brew more, since the flood had ruined the barley crop, and the scanty replacement had been sown so late and under the wrong aspects of the moon.

Katherine sighed again. She had been up since daybreak, caring for the babies and trying to help poor Hugh before attending the Queen's memorial Mass. She pulled Tom's cradle close to Blanchette and, curling around her sleeping children, nestled into the straw.

It was thus that the Chaucers found her a half-hour later. They had dismounted by the church, tied their horses to the lych-gate and walked across the drawbridge to inquire, because Philippa, on seeing the manor house, had been quite sure that there was some mistake. She was accustomed to royal castles and the palatial homes of noblemen, and nothing through the years of their separation had arisen to shake her conviction that her sister's enviable marriage to a landed knight presupposed baronial grandeur.

"I'll take oath this can't be Kettlethorpe Manor," she said to her husband as they entered the courtyard. "It must be the bailiff's home." Her high insistent voice penetrated Katherine's dreams, and the girl stirred and slowly raised her head. The movement caught Philippa's incredulous eye, and she turned.

"Blessed Saint Mary - 'tis Katherine! God's love, sister, do you sleep on straw, like a beast, here?" The shock momentarily outweighed Philippa's affection and she spoke in sharp dismay.

Since the day was so hot, Katherine had after church laid off her linen coif and bundled her masses of ruddy hair into a coarse hemp net - like a byre-maid, thought Philippa. Bits of straw were stuck amongst the damp curls that clung to the girl's cheeks. Her gown was of blue sendal but looked much like a peasant's kirtle, since Katherine had not covered it with the sideless furred surcote which befitted her rank; and worse than that, she had looped the long skirt up beneath her girdle so that it was plain to see that she wore no hose. Bare white ankles showed above the scuffed soft-leather shoes. Philippa was appalled.

Katherine blinked, still thinking that these two whom she had not seen for so long were part of her dream - a short plump young couple, both dressed in black, both gazing at her with, surprise - then she scrambled to her feet with a glad cry and rushing to her sister threw her arms around her neck. Philippa returned the kiss, but Geoffrey, who knew the signs, saw what his wife's next words would be like, and, himself kissing Katherine on each cheek, said quickly, "By God's mercy, my dear - you're fairer than ever - and these are the babes? La petite Blanche, wake up, poppet! Your uncle has brought you trinkets from London! And there's a fine fat boy! We'll have one just like him, eh, Pica?" and he pinched his wife's round cheek.

"With Christ's grace," said Philippa glancing at the babies, but not to be diverted. "Katherine, is this the way you keep your state as lady of the manor - what example do you give your servants? And-" She glanced frowning around the littered courtyard and at the small building and one low tower; her sharp eyes noted the crumblings between the aged stones, the mouldering thatch on the roof, the general air of dilapidation, and she finished more feebly," 'Tis not what I thought."

Katherine smiled at her sister, even welcoming the old atmosphere of reproof and admonition which took her back to childhood. "Kettlethorpe is small," she said temperately, "but we did well enough until this summer. We had a fearful flood and all our crops washed away. Our flocks too. Were it not for produce from our holdings at Coleby, which is on higher ground, I don't know where we'd turn. Hugh is hunting in the forest, but game is hard to find, the wild things were all driven out by the waters."

"Ah, yes," said Geoffrey sadly, "throughout England there's the smell of doom. We saw as we came north fires, famine - but here at least you've no plague - -"

Katherine glanced in sudden fear at her babies. Tom slept on, but Blanchette hid behind her mother and peered round at the strangers. "I've heard of none," she said, and crossed herself. "Is it so bad in the south - you - you haven't lost -"

She faltered, glancing at their mourning clothes which were of rich sable wool trimmed with velvet and strips of black fox. Philippa's tightly coiled dark braids were bound with an onyx and silver fillet, and beneath it her earnest face was round and neat as a penny.

"Oh, no," said Philippa, "we wear this for the Queen, God assoil her gentle soul. The suits were given us by the King's orders," She spoke with a certain complacence, though she sighed. She had been devoted to the Queen and now had no idea where her next permanent home would be, since Geoffrey was away so much on King's business and even now must return to Dover, then report to the Duke of Lancaster at Calais.

She was fond of Katherine, but in view of what she had already seen of Kettlethorpe, she could not but be doubtful about the protracted visit Geoffrey had planned for her. The Queen had left her a pension of a hundred shillings yearly, and Philippa suspected with natural annoyance that she might have to pay board instead of living in the luxurious elegance she had imagined, while saving her income for the benefit of her long-awaited baby.

"We had the Queen's Requiem Mass today - you hear the passing bell," said Katherine diffidently. "You mustn't think we don't sorrow for her here, though we are so far away."

Geoffrey's bright hazel eyes glanced at the girl and softened. Ever quick to catch human overtones, he heard the wistfulness in her voice, thought that she was more unhappy than she knew and bore herself with a rather touching gallantry. It was true that she was more beautiful than ever, her cheeks like red and white daisies, her lustrous eyes grey and soft as vair; she glowed with bright health though she was slender as a birch. Despite the two children and despite her eighteen years, there was still something virginal about her.

He reflected that it was not thus he had expected Katherine to be now, when he had first seen her at court three years ago, when he had said that she had le diable au corps and thought her a flame to light man's lust. He had thought that there was the mark of destiny upon her. And he had been wrong. The stars had held for her, it seemed, only the fate shared by thousands of other women; motherhood, housewifery, struggle and - as he at once discovered when Hugh returned - the endurance of a difficult, ailing husband.

By the time Hugh came in from hunting, the Chaucers had been settled in Lady Nichola's old tower-room and were in the Hall awaiting supper.

Hugh made an effort to greet his guests cordially. He sent Cob to broach the last keg of ale. Little Cob, the erstwhile spit-boy, was now nineteen and had been promoted to servitor, though he was still flax-haired and undersized, also sulky, for he liked farming and loathed his kitchen duties. He brought up a flagon of ale to the Hall and spilled some, at which Hugh gave him a savage kick on the shins.

Then Hugh filled the wooden mazer, said "Wassail," drank and passed it to Philippa as hospitality demanded. She answered "Drinkhail" uncertainly before she sipped. These Saxon customs were seldom seen at court, and Philippa tightened her lips. The ale was inferior and besides, she was used to wine. If it weren't for the plague - she thought unhappily - but there was no other place for her to go, and anyway she dared travel no farther in her condition

The wassail cup passed from Katherine to Geoffrey and back to Hugh, who took a deep draught, and spat most of it out on the rushes. Swallowing started the gripes. "What news of the Duke in Picardy?" he said through his teeth to his brother-in-law. "How goes the war?"

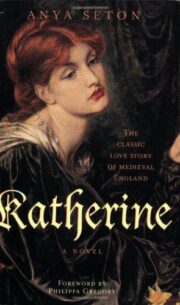

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.