It was past high noon when Katherine came to herself again and heard the subdued muttering of women's voices, and at first she could not think what had happened, but lay in a vague dream watching through heavy lids the dance of dust motes in a sunbeam. She turned a little in the bed and her hand fell on her flat belly, then she remembered and started up with a cry, "My baby!"

The kind round face of Parson's Molly bent over her. "Here, lady, here's the tiny maid, all snug and swaddled and content." She put the infant in the crook of Katherine's arm. "As fine and fair a babe as I ever see," and over Molly's shoulder Milburga's frightened, peering face nodded agreement.

Katherine looked down at the tiny head covered with darkish fuzz, the crumpled nose and moist pink lips. "Put her to the breast," said Molly, pulling down the sheet, "let her suck to bring the milk in." Katherine felt the hungry tug of the little mouth, and a wave of delight such as she had never known washed through her body. She felt that they two were floating in a golden bath together. The dark doings of the night before seemed a foul dream long past, neither fear nor pain could touch her ever again, for here was love come at last, incorporate in this tiny thing that breathed and nestled and belonged to her alone.

When the baby fell asleep, she moved it so that its head lay against her cheek and slept too. The women let her be while they whispered fearingly together.

No one knew what the Duke would do to them. His anger had been terrible as he came down the solar stairs into the courtyard when the housefolk came stumbling and lurching back across the drawbridge from Ket's rites. He had not whipped them nor berated, but his eyes had flashed like swords and the tone of his voice as he gave them orders banished their drunkenness like a purge.

They had run frantically to obey him, themselves appalled when they found out what had happened in their absence. The Lady Nichola, sobbing and beating her breasts, had been already chained to her bed in the tower by the Duke's men, for he had brought five with him.

And when Parson's Molly came running to the manor from the village, they found what sad plight their little mistress was in, wallowing unconscious in fouled sheets and the stench of birth - blood, while the babe lay naked, though unhurt - praise be to the Blessed Virgin!

The women now heard the shouts of men - at - arms below, and a squeal of pain from Toby as one of the Duke's retainers cuffed him; and they huddled by the fire, glad of the sanctuary of the birth - room. Then they heard footsteps on the wooden landing and a knock outside. Molly's fat cheeks mottled, but she went to the door and opened it bravely. She curtsied as she said low, "Our lady sleeps, my Lord Duke, but we've washed her and the babe."

John pushed her aside and strode to the bed. He stood looking down at Katherine. White and spent as a plucked windflower she seemed to him, lying there defenceless with her baby next her cheek. And the small happy smile on her pale lips increased his pity. It was pity that he felt and again that strange urge to protect that he had known when he had kissed her a year ago, but now there was no desire mingled with this other feeling. She seemed to him as childlike and pure as his own daughters. Her long lashes quivered and she opened her eyes. They no longer reminded him of Isolda's for there was in them no urgency, no appeal - clear and untroubled they looked up at him.

She saw him through a dreamy haze, so big and shining with his tawny head, a topaz velvet tunic over powerful chest and shoulders, and eyes blue as speedwells against his sunburned skin.

"I don't wish to disturb you, Katherine," he said gently. "I came to see how you did - and the babe." He took her hand, noting with tender amusement that it was still somewhat rough and the nails bitten.

"I do well, my lord." She let her hand He trustingly in his, scarcely aware that it did. "Is she not lovely?" - she nuzzled the baby's head.

John smiled assent, though the infant looked like all others to him and not nearly so comely as his own son, who had lost the new - born pulpy redness.

"How came you here, my lord?" she asked, drawing her arched brows together. "It seems strange - now I begin to - to wake."

"Having business in Lincoln, I thought to pay you a May morn visit, and - I scarce expected to be so opportune." He frowned, glancing at the frightened women by the fire. "I thought you might like news of Hugh."

"Ay - where is Hugh?" she murmured.

"Still in Castile, at Burgos with my army but unharmed. I'll send him back soon. I see you sorely need him."

"But you're here," she whispered smiling, drugged with the torpor of exhaustion and peace.

"Not for long - my ship waits for me at Plymouth. I came back because I have a son."

"Ah yes," she said. "I knew - I had forgot - how does my Lady Blanche - - "

"Fairly," he said and no more, seeing that Katherine was not fully awake and making an effort to be courteous. He dropped her hand and turned to the window.

Blanche was not churched yet. He had returned to find her very ill with milk fever and one of her legs so red and throbbing that she cried out when it was touched. But the blissful shock of his unexpected return had improved her at once.

She had been well enough for him to leave Bolingbroke and make this hasty trip to Lincoln to inspect its castle, which he owned. Conferences with the constable had taken little time and it had been on impulse that he decided this fine May Day morning to ride on to Kettlethorpe and see Katherine. In truth, he had not thought of her at all these last months - - months of triumph, culminating in the glorious victory at Najera on Saturday, April 3. The memory of that arid sunbaked Castilian plain gave him sharp joy.

With the always able help of Sir John Chandos, and his English bowmen, the Duke had led the shock troops in the vanguard of the Prince of Wales' army, and they had loosed a barrage of whirring arrows that turned the tide almost at once. The Castilians fell back, they disintegrated, they ran, and, forced into the flood - swollen river Najerilla, they drowned - twelve thousand of them. The rushing waters had turned red as wine. By noon the battle was over and King Pedro, sobbing with gratitude, had kissed his champions' hands, had knelt on the blood - soaked earth before the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Lancaster.

It was unfortunate that amongst the bodies of the Castilian slain they could not find that of the bastard Trastamare, but otherwise the victory had been complete even to the capture of the redoubtable Sir Bertrand du Guesclin. All the victors had held high feast in Burgos, Castile's fair capital. And there, when the messenger from Bolingbroke found him ten days later, John discovered that he had fresh cause for exultation. His son Henry had been born on the same day as the triumph at Najera, surely a most auspicious bit of fortune. He gave thanks in the cathedral and determined to make a quick trip home to see his son - and Blanche. But neither sentiment nor paternal pride alone could justify the time expended on such a voyage, for there were still angry matters to smooth out in Castile and his brother needed him. So John bore letters to the King at Westminster and, more important, had seized the opportunity to replenish his purse from funds held by his receiver - general at the Savoy. The campaign, however glorious, had been expensive.

These matters passed through his mind as he stood by the window and he almost regretted the impulse that he sent him here this morning; for he saw that he could not leave at once as he had planned, while Katherine lay helpless, at the mercy of her serfs and the mad woman Nichola. Yet he was sorely pressed for time and turned plans over in his mind which might best ensure her safety until he could send Hugh back.

He returned to the bed and saw that she had awakened, and was softly kissing the baby's head. "Your villeins must be punished, Katherine," he said, smiling at her. "I understand from your bailiff that you and he forbade their extraordinary rites last night and yet they left you here alone."

"That was my fault, my lord." Through this dreaming bliss she felt no anger towards anyone. "The midwife would have stayed with me but I wouldn't let Milburga fetch her."

The two listening women looked at each other. Molly whispered, "Our little mistress is kind." Milburga shrugged. They held their breaths.

John shook his head impatiently. "These serfs cannot be permitted to defy you - there's no strong arm on this manor, that I see well, nor can I forgive Swynford for leaving you in charge of such a bailiff - a dead man - it was dangerous folly - - " His anger rose at Hugh, though in Castile he had felt none, for Hugh had again proved himself a powerful fighter.

"Poor Gibbon does the best he can," said Katherine softly. "It's I who have been lax."

"Nonsense, child! It's only that you're far too young to have learned the arts of ruling and you must have help. I've decided what shall be done."

"Yes, my lord," said Katherine, humbly. Though he was but twenty - seven he seemed to her the embodiment of unquestioned authority as he stood there, his shining head thrown back, his eyes stern. He spoke to her as her father had used to long ago. There was no tension between them now, nor did she remember that there ever had been. He was but her overlord and her rescuer.

"I shall leave one of my men here to guard you. A Gascon named Nirac de Bayonne and - for a Gascon - trustworthy." John smiled suddenly. Nirac amused him with his quick tongue, nimble wits and sly humour. Nirac was a man of many parts, he could concoct licorice potions or spice hippocras; he could fight with the dagger and sail a ship, the latter accomplishment learned during years of smuggling and freebooting between Bayonne and Cornwall. Though Gascony and the rest of Aquitaine belonged to England, Nirac had not troubled himself about allegiance, until the Prince of Wales' officers caught him and pressed him into military service in the recent Castilian war. And that temporary allegiance would have dissolved as soon as he had been paid, except for the entirely fortuitous circumstances that John had saved his life at Najera.

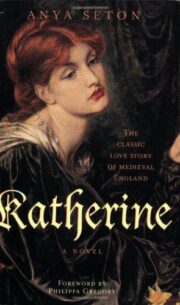

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.