The other pilgrims shrank back, murmuring and exclaiming. It was a sign, they said, that the Holy Cross was angry with the knight. It wanted none of his worship and had flung off his sword to point in such a way that he must leave the sanctuary. And they looked askance at Hugh, wondering what secret sin he might be guilty of.

Then a fat monk hurried up from behind the shrine, and said that indeed it was a sign, almost a miracle, but they must be careful of interpretation. He deemed that the Holy Cross wished the sword offered to it as a gift, that only in this way could the knight appease divine wrath.

Hugh stood silent on the top step gazing down at his fallen sword. The scabbard was of silver-gut intricately carved, the sword itself of finest Damascus steel, the hilt encrusted with small rough emeralds. This sword had been his father's and had saved Hugh's own life in France and in many a skirmish since. He looked down at it with fear, feeling that in some way his manhood, too, had fallen from him, and he shook his head muttering, "I will not give up the sword."

The people jostled and exclaimed again, whispering that hell fire would claim the knight for such disobedience, and one old crone lifted her wheezy voice to cry that she had seen a great white hand dart through the air from the Holy Cross and strike the sword off the knight's girdle.

The monk peered into Hugh's shut face, and finally said that there might be another way to avert wrath. The shrine had need of embellishment. The Holy Rood at Bromholme, though but a mean inferior miracle-worker, had a new cloth of woven gold, but there was none like that here. It might be that for the price of the sword the Blessed Cross would be appeased.

Hugh looked from the monk to the heavy black cross. A tiny image of the Saviour had been fastened to its gleaming surface, but the cross breathed neither of pity nor redemption. Like the stone idols his ancestors had worshipped, it towered dark and sinister above him. What portent was this for his marriage? He saw that Katherine had drawn aside from the other pilgrims and stood watching, her cheeks gleaming white in the darkness of her hood.

He opened his purse and put four marks into the monk's outstretched hand. The monk's splay fingers closed over them. He murmured benediction and walked quickly back behind the shrine. Now the people murmured again, some thinking the knight got off too easily, but most thought that so great a sum would surely propitiate the cross.

Hugh descended the steps, picked up his sword and strode from the church, while Katherine walked after him. She had been frightened at the shrine when the sword clattered down and the people cried it was a sign. But when she saw fear on Hugh's face, too, she had felt a twinge of doubt. Had it been the Blessed Virgin or a saint he had somehow offended, she would not have questioned, but this lumpish black stone which contained not even a relic of the true cross seemed to her an ugly thing. Might it not have been that the sword had fallen because Hugh, hindered by his wounded hand, had not fastened it properly? And the fat monk with greedy piggish eyes, had he not been overglib in his interpretations? Yet, she realised with sudden shame, these were impious thoughts, and perhaps she entertained them only so that she need not think of the moment which was fast approaching.

They went to a mean and shabby inn, The Pelican, because Hugh had given up nearly all the money that he had, nor would he seek free shelter for them at the abbey hostel, where they would have been separated into different dorters.

The stuffy little loft-room assigned them at the inn was no fitting bridal bower. The straw was mouldy on the square box bed and hidden but in part by stained old quilts. Smoke seeped up through the rough planking from the kitchen fire below and in the dusty corners black beetles scampered.

Hugh looked sideways at Katherine, then he shouted for Ellis to bring up a flagon of strong ale, and of this he drank cup after cup in frantic haste as though he drank for a wager. He offered some to Katherine, but she merely wet her lips, and gave him back the cup. She had become very still, and stood by the tiny-window, gazing out into the twilight towards the abbey. It seemed to her like a crouching beast; the chancel was its head, the double transepts its arms and legs, the nave its massive tail. A monster, ready to spring at her through the dusk. She turned her head a moment when Hugh banged down the oaken strip that bolted the door. She saw that his face had grown dark red, and heard the sound of his breathing. She shrank nearer to the window, and her hand clenched on the sill.

He came up behind her, gripping her shoulders with furious strength. "Katherine!" he cried, his voice as though he hated her. "Katherine - -" The pain of his grip on her shoulders almost made her scream, and yet she knew that his fury was not directed at her, and through her fear, pity flickered and was gone.

In the quiet dawn light after Katherine had been weeping for many hours, she heard the nightingales singing from a thicket behind the inn. She lay and listened to their carefree bubbling song and at first it seemed to her an unbearable mockery. She eased her bruised body into a new position as far on the straw from Hugh as possible. He lay on his back snoring heavily; the room stank of sour ale and sweat. But as she listened to the nightingales, her tears dried, some peace crept into her heart, with a tough strength. She thought that no matter how her body was violated, it could not affect her unless she let it. She was still Katherine, and she could withdraw with this knowledge into the secret chamber where no one else might penetrate by violence. She could surround herself with an impregnable wall of hidden loathing and contempt.

As she thought this the abbey bells began to call the monks to Matins. The clangour of the great-throated bells and then the chanting of male voices drowned out the nightingales. Her hand went to her beads, and she began the Ave, but the beads slipped from lax fingers. What can the spotless Queen of Heaven know of that which befell me this night, what can Saint Catherine know, who was a virgin martyr? Leaning down from their purity, they may be gracious, but they cannot truly understand. So I am alone. I need nobody else. All that must be, I can endure alone.

Hugh stirred and murmured in his sleep. He reached his arm out as though he searched for her. She lay motionless, watching him, coldly, through narrowed lids. He looked younger in his sleep, yet his mouth drew in tight at the corners as though he suffered. His groping hand found the spilled masses of her hair and grasping a strand he pulled it to his cheek so that the jagged scar lay on her hair.

His gesture did not touch her, he was as alien to her now as had been the panting, heaving beast earlier. But she would never be afraid of him again, nothing that he did could touch her. She would be a dutiful wife, she would accept the hard lot that fate had given her, but yet she would be free. Because he loved and lusted and floundered, while she did not, she would be forever free.

Thus Katherine thought on her first morning of wifehood in the ugly loft-room of the inn at Waltham Cross.

On their way up to Lincolnshire, Hugh, Katherine and Ellis spent three more nights on the road. Katherine was neither happy nor sad. She treated Hugh in a cool, friendly enough manner, acceded indifferently to his nightly demands, and yielded nothing of her inward self. He marked with jealousy that she spoke to Ellis in the same polite aloof way she spoke to him, and that all her warmth and tender pleasure went to the little mare he had given her. She had named it Doucette, saying that it was sweet as the doucettes of cream and sugar she had tasted at Windsor, and she was forever patting its neck and murmuring little love words to it. Hugh felt hot anger at the horse, but this he tried to hide, being afraid of Katherine's scorn.

He could not have put words to his feelings, but in a confused way he realised that when he had forced and then possessed her body she had somehow managed to escape him completely. But still he thought that she would come closer to him later, and he reminded himself often of how young she was, though very young she did not seem to him. For he had never seen her dance and romp as she had in London on May Day, nor had he ever heard her joyous quick laughter.

At Wednesday noontime, when they were a few miles south of Lincoln town, they turned off the Ermine Way and climbed the Ridge to see Hugh's smaller manor of Coleby, which he held in fee from the Duke of Lancaster. This manor was much neglected, its house nothing but a crumbling shell, where Hugh's reeve, a sottish drunken lump of a man named Edgar Pockface, dwelt in the leaky hall with a brood of fifteen children. The reeve came lurching out of the door as he heard horses in the weed-choked courtyard and stood aghast at seeing his manor lord. He tugged his Forelock and began mumbling. Hugh dismounted, glaring around at the tumbledown dovecote, the byres and stables half unroofed, the scanty piles of fodder mouldering unsheltered on the dank earth.

"By God's blood, Edgar Pockface!" he cried. "Is this the way you oversee the villeins, is this the care you give my manor!"

Edgar mumbled something to the effect that the serfs were unruly, that they refused to do their regular week-work for their lord, let alone the boon-work, that it had been so long since Sir Hugh or his bailiff had come here they had near forgot they were not freemen.

Hugh raised his hand .and struck the stupid face a vicious blow across the mouth. "Then this will remind you that you are not free!"

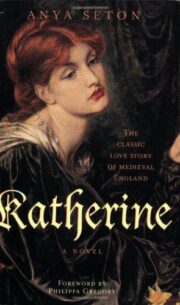

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.