Her heart cried out that she did not love him, that the thought of lying in his arms sickened her. Reason answered that at thirty-six she should be finished with youthful passions and love-longings, that stubborn fidelity to a dream long past was stupid.

By day, it was only when she saw his traits in his children that she thought of the Duke. Young John looked most like him, the tawny gold hair, the arrogant grace of movement. But Harry had his voice, deep, sometimes sarcastic, sometimes so caressing, that it turned her heart over. They all had his intense blue eyes, except Joan.

But by night, sometimes she was with him in dreams. In these dreams there was love between them, tenderness greater than there had really been. She awoke from these with her body throbbing and a sense of agonising loss.

She had had no direct communication with him in these years, but he had been just, as she had known he would. There had been legal documents: severance papers sent through the chancery, which allowed her to keep the properties he had previously given her, and made her a further grant of two hundred marks a year for life "in recognition of her good services towards my daughters, Philippa of Lancaster and Elizabeth, Countess of Pembroke." No mention of his Beaufort children, but Katherine understood very well that this generous sum was to be expended for their benefit, and scrupulously did so.

Finally there had been a fearsomely legal quit-claim in Latin which the Duke's receiver in Lincoln translated for her. Its purport was a repudiation of all claims past, present and future which might be made on Katherine by the Duke or his heirs, or that she might make on him. Merely a matter of form and mutual protection, explained the receiver coldly, and added that His Grace with his usual beneficence had ordered that two tuns of the finest Gascon wine be delivered at Kettlethorpe as a final present.

So that was how it ended, those ten years of passionate love. A discarded mistress and her bastards, well enough provided for; a repentant adulterer who had returned to his wife. A common tale, one old as scripture. The Bishop of Lincoln had not failed to point this out in a sermon, with a reference to Adam and Lilith, and a long diatribe about shameless, scheming magdalenes. This sermon was preached at Katherine during the first hullabaloo after her return.

Later the bishop's sensibilities had not been so delicate when Katherine leased the house on Pottergate from the Dean and chapter for a sum double its worth; but she no longer attended Mass in the cathedral, she went instead to the tiny parish church of St. Margaret across the street.

She could not have endured the cruel humiliation that continually assailed her without the memory of Lady Julian, and the golden days in Norfolk. "This is the remedy, that we be aware of our wretchedness and flee to our Lord: for ever the more needy that we be, the more speedful it is to draw nigh to Him." These words always helped, yet on this problem of Robert Sutton she had received no answer. The serene certainty which she had come to rely on after prayer failed her in this.

That afternoon, in anticipation of the wool merchant's visit, Katherine kept her three boys with her. Though they were wild to get out on the exciting streets to watch the preparations for the King's procession, she had asked them to stay awhile, partly because they gave her protection, partly to observe closely how Robert would treat them.

John understood at once. The moment she mentioned her expected visitor, he drew his mother away from the younger boys and putting his hands on her shoulders looked steadily into her face. "Are you going to consent, my mother?" he asked. He was almost fifteen, taller than she was now, broad-shouldered and manly in his school uniform of grey cloth. But she knew how he longed to change it for armour, how he longed for knighthood and deeds of valour, for the life he saw his legitimate half-brothers lead, Henry of Bolingbroke and Tom Swynford.

"Johnny - I don't know," she said sighing. "What shall I do?"

" 'Twould make it easier for you!" he said slowly. Under the new golden fuzz his fair cheeks flushed. "I can't protect you as I would." He gulped and flushed redder, began to twiddle with the flap of his quill case. "But I will! Wait, you'll see! I'll earn my knighthood some way. Mother, I can best all the lads tilting at the quintain. Mother, let me enter the Saint George Day's tournament at Windsor, let me wear plain armour - no one shall guess that I'm - I'm-" Baseborn. He did not say it, it hovered in the air between them.

"We'll see, dear," she said, trying to smile. John's dreams were impractical, but he should at least be attached to some good knight as squire, someone who would honour his royal blood and not take advantage of his friendless position.

And the two other boys. She looked at Harry, sprawled on his stomach by the fire, reading as usual. He had ink on his duckling-yellow forelock, ink stains and penknife cuts on his grimy hands. A true scholar was Harry, with a keen shrewd mind beyond his years. He gulped knowledge insatiably, and yet retained it. He was determined to go to Cambridge, to Peterhouse, and train for minor orders at least; any further advancement in the clergy would take great influence - and money. A bastard could not advance in the Church without them. Bastardy. How often had she tried to console the elder boys as they had grown into realisation of the barrier that held them back from their ambitions, pointing out that they were not nameless, that their father had endowed them with a special badge, the Beaufort portcullis, and a coat of arms, three royal leopards on a bar. She reminded them that William of Normandy, England's conqueror, was not true-born. These arguments seemed to comfort the boys. At least they had both ceased to distress her with laments. But they were thoughtful of her always. In their different ways, they loved her dearly.

Tamkin was still too young to fret about his birth. He was a happy-go-lucky child anyway, and at ten lived in a boy's world of sport and play. A healthy young puppy, Tamkin, and at the moment engaged in teasing Harry by rolling dried acorns across his book. This ended in a scuffle, and then a rough-house. Chairs were overturned, the floor rushes flew about the pommelling, shouting whirl of arms and legs when Robert Sutton walked in.

"By God, lady!" he cried above the rumpus, " 'Tis like the mad cell at the Malandry in here! Your lads show you scant respect."

Tamkin and Harry disentangled themselves abruptly. They stood up panting, red-faced. "We mean our lady mother no disrespect, Master Robert," said Harry arranging his torn tunic, and eyeing the wool merchant coldly.

Robert, glancing at Katherine's watchful face, changed his tone. "Good, good. I'm sure you don't. Boys will be boys, ha? I've brought you lads something." His full swimming eyes veered to include John who stood very stiff and quiet beside his mother. "It or they rather, are in the courtyard, waiting for you."

"Oh what, what?" cried Tamkin jumping up and down.

"Go and see," said the merchant benevolently.

John and Harry gave him a restrained, considering look, but they went off with their excited little brother.

"My best hound bitch, Tiffany, has lately whelped," Sutton explained to Katherine, sitting down opposite her. "I've brought each of your lads a pup. The strain have the keenest noses in Lincolnshire."

"That's very good of you, Master Robert," said Katherine with sincere gratitude. The boys had no blooded hunting dogs, and made do with the Kettlethorpe mongrels.

"And I've brought Joan a yellow singing bird that came from the coast of Fez. She must keep it warm and tend it well."

"Ay - and thank you. It'll delight her," said Katherine.

He was not normally perceptive, but with regard to Katherine this middle-aged passion that had come to him made him observant. He saw a shadow in her lovely grey eyes, and a tightness about the mouth which still retained the curves of youth. He put his pudgy hand on his velvet-draped knees and leaning forward said anxiously, "What troubled you, just then, sweetheart?"

He is good, she thought, he is kind, if the boys are jealous they'll get over it. I'll say yes, but I must be frank with him in all things first.

"It was this," she said speaking with effort. "I had a child - once - who loved singing birds - Blanchette - -"

"To be sure, and I remember the little red-haired maid, years ago at Kettlethorpe," said Robert heartily. "Too bad she died, God rest her soul." Pity it wasn't one or more of the bastards died, he thought. Ah well, one must take the rough with the smooth.

As Katherine did not speak but gazed into the fire, he said on a brisker note, "You must forget the past. It does no good to brood."

"No, of course not." She turned and looked at him. At the sleek curls of beard on his well-fed jowls, at the network of tiny purple veins in his cheeks, at the heavy gold chain around his massive crimson velvet shoulders, at the badges of office on his arm - former mayor, member of Parliament, master woolmonger - at the heavy-lidded, slightly bloodshot eyes that answered her gaze with kindling eagerness.

"It does no good to brood," she repeated, "and I'll try to forget the past."

"I'll make you!" he cried thickly. "Katherine, you know what I've come to say. We're not children. You shall be Mistress Sutton. By God, you shall be mayor's wife next year - when Father's out and I'm re-elected. You shall hold your head up in this town, and be damned to all of them. They dare not gainsay a Sutton. I'll not say I haven't thought twice about it, and my father and brother - well, no need to go into that, they'll do what I tell 'em to. We Suttons stick together and they have to admit 'tis not as though you came to me penniless. Nay - I've shown 'em that the Beauforts are provided for, and you have property, a tidy parcel. You'll soon see how your manors'll flourish when I've full control. Not but what you've acted cleverly enough for a female. As you know, I was against your freeing the serfs - but it's not worked out so badly, I'll admit, long as they pay their rents. But you can get more out of the manors than you do. There's a new breed o' Cotswolds I shall try at Kettlethorpe, I think the pasturage near Foss-

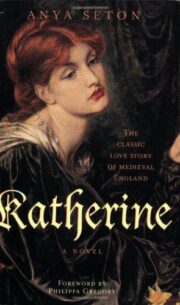

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.