"Ye can't go up there, woman!" squealed Elias, jumping up and shaking his fist as he hobbled after Katherine.

Cob gave him a negligent shove and gestured with his knife. "Me whistle's still dry. Where's more ale? Ye've not earned your noble yet, not by a long shot." He grinned and pricked Elias on his skinny shank. "I'll have that flitch o' bacon too, what's hanging from the rafter, and I dare say ye know where white bread be stored. I've a fancy to taste white bread at last."

While Cob made himself comfortable in the kitchen, Katherine found her way to the chamber loft. The two great beds and the sliding truckle were all neatly made and covered with down quilts. She lay down on the bed which she had once shared with Hawise. Always when she lay down to rest her longing prayers turned to the Duke. Now for a moment she saw his face but it was far away, tiny; then a hand holding a threatening crucifix thrust up as barrier before John's face, blocking it off. Her head throbbed agonizingly. She moaned a little, and closed her eyes.

When Master Guy returned home, it was near to sundown and the grave issues of the rebellion so perturbed him that he gave scant attention to the presence of a ragged little knave in his kitchen, or to old Elias' stammered excuses.

When he understood from Cob that Lady Swynford was sleeping upstairs, having taken refuge here after the burning of the Savoy, Master Guy banged his pudgy hand on the table in exasperation, crying, "By God - why must she come here!" But when Cob had tried to go on and tell him of the gruesome happenings in the Savoy and the dangers they had run in London streets to get here, Master Guy interrupted, shaking his fat jowls impatiently. "Ay - ay, I know there's been hideous deeds everywhere this day. Well - let her be - let her be - but I canna concern mesel' wi' her, one way or t'other. Nor ye neither," he said to Cob. "Ye can rest a bit, then out ye go. I want none o' the rebels in here."

Today at the distress meeting in Fishmongers' Hall, first, Mayor Walworth had come to tell his fellow fishmongers that all loyal citizens were to be alerted - here he had glanced frowning at the empty chairs of the aldermen who had opened the Bridge and joined the rebels - that since Wat Tyler's early promises of good behaviour and no violence had not been kept, and since the rebels were now most threateningly encamped around the Tower and besieging the King, a fierce and sudden counter-attack was being planned.

The King's regiment within the Tower would be joined by Sir Robert Knolles' huge force of retainers who were quartered in his inn this side of Tower Hill, while all the Londoners who wished to rid their city of the insurrectionists must arm and strike at the same time. It had seemed a good plan to the anxious fishmongers and they had started to organise the runners who would alert the other guilds and burghers while Walworth returned to the Tower.

But no sooner started than the whole scheme had been countermanded. A panting King's messenger arrived at Fishmongers' Hall bearing an official missive. There was to be no attack made on the rebels after all, conciliation was to be tried first. The messenger had been present at the King's Council and amplified his document. He told the fishmongers that the King had ordered the rebel army to meet him at seven in the morning for conference at Mile End, a meadow two miles to the east of town. This would give opportunity for the archbishop and treasurer to escape by boat while the savage mob who howled for their blood were drawn off to parley with the King.

Master Guy lumbered up to look to the fastenings of his house before going to bed, and was reminded of Cob, who lay curled up snoring on a bench. "Out wi' ye - now," he cried, shaking him.

Cob did not protest, for the huge fishmonger was fully armed; besides Cob was rested now and full of food, and not ungrateful. "Ay - I'll be off, thank 'e, sir." He yawned and bowed and docilely went out upon Thames Street while Master Guy barred his door behind him.

Cob finished out his sleep on a stone bench in St. Magnus' church porch and awakened when its bells rang out for Prime. This Friday, June 14, was another fair warm day, and Cob felt revived interest in the great cause which had brought him into London. He munched on the delicious white bread and bacon with which he had prudently stuffed his pockets, and glanced towards the fishmonger's house where Lady Swynford slept, devoutly glad that he was rid of her and wondering that he had taken so much pains to care for her yesterday. Her and her purse full of jewels and gold! A murrain on her and all her kind, thought Cob, bitterly regretting that he had not taken opportunity to steal upstairs and relieve her of that purse before Master Guy came home.

"When Adam delved and Eva span, who had gold and jewels then?" Cob chanted, raking his fingers through his hair and squashing a louse that ran out of it. He trotted off down the street towards the Tower and the rebel camp beyond it on St. Catherine's Hill.

Here Cob was swept up by the wild excitement. Their leaders Wat Tyler, Jack Strawe and the priest John Ball, were all a-horseback, galloping amongst their forces, which numbered by now nearly eighty thousand men. "Mile End! Mile End!" they shouted. The King was to meet them at Mile End and listen to their plans in person. "Onward march to Mile End to meet the King!"

Cob surged forward with a great multitude of them, swarming and trampling over the fields until they reached the meadow where the little King awaited them.

Richard sat pale and stiff upon his brightly caparisoned white horse. His crown was no more golden than his long curls, and in Cob's eyes and those of his fellows Richard's royal beauty shone round him like a halo. "God bless our King!" they cried. "We want no King but thee, O Richard!" All bowed their heads, and many genuflected humbly.

The King smiled at them uncertainly and waved his hand in response, as Wat Tyler rode up to him for parley.

A dozen nobles were gathered behind the King - those who had been with him in the Tower: the Lords Warwick and Salisbury and Sir Robert Knolles, grim fighters all three and of proven courage in war, but this aggression from a mob of despicable serfs and peasants was so alien to their experience that they had floundered this way and that, quarrelling amongst themselves.

The King's beloved Robert de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, had drawn apart from the others and watched from beneath raised eyebrows, which were finely plucked as a woman's. With delicate fingernail he flicked a tiny blob of mud off his rose-velvet cote, and as Wat Tyler approached them, de Vere sniffed ostentatiously at a scented spice ball that dangled from his wrist.

The King's uncle, Thomas, Earl of Buckingham, was there too, his truculent black eyes flashing, his swarthy face suffused with impotent rage, but even he had sense enough to hold his tongue and stay his sword arm until they saw what might be accomplished first by guile - and by a further measure which was even now in progress back in the Tower.

Sudbury's and Hales' attempted escape by boat had gone awry earlier, ill timed and clumsily executed. The archbishop had been recognised by rebel guards on St. Catherine's Hill and had regained the safety of the Tower just in time. But not for long. As the King left for Mile End, Buckingham had issued certain orders, not mentioning them to Richard, who was often oversqueamish. Buckingham had decided that the safety of England and the crown should no longer be jeopardised by two cumbersome superfluous old men.

The little King gave no sign of fear as he nodded graciously to Wat and, after listening a while, readily gave the verbal agreement his advisers had told him to. The abolition of serfdom and a general pardon for all the rebels - these were what the tiler demanded first, and "Ay - it shall be done!" cried Richard in his high, pretty, childish voice. "The charters shall be prepared, ye shall have them on the morrow."

This was not all that John Ball and Wat had drawn up as their requirements. It did not answer their demands for the abolition of private courts, for freedom of contract, disendowment of the clergy, land at fourpence an acre rent, but Wat thought it better not to press for too much at once. These other matters could wait, since the greater part of their glorious goal had been so comfortably achieved.

He seized Richard's hand and kissed it vehemently. Then he jumped on his horse and standing in the stirrups shouted to the silent straining mob, "The King has agreed there's to be no more bondage!"

"Free?" whispered Cob, swallowing. A shiver ran down his back. No more hiding in the forests or the City. No more heriot fine, no fines, no boon-work. He could go back to Kettlethorpe and do as he pleased on his own croft. He could keep his ox and earn money for his labour. A freeman.

"I didn't rightly believe 'twould ever happen," he whispered. He put his knuckles to his eyes, and a sob rose in his throat. All around him men were leaping, laughing, crying, so that it was hard to hear what else Wat said, but the tall ploughman passed it on.

" 'Twill take a little time to get our charters, the parchment what'll prove we're free. Wat says we'd best wait on St. Catherine's Hill."

Cob nodded, for he could not speak

He and many others took their time about wandering back to the City. The sun shone on them, the earth of the road was brown and warm beneath their feet, and the brooks gurgled joyfully through the meadows. The leaping wild excitement died down and they smiled at each other quietly, their eyes shining. Some sprawled upon the grass apart, thinking with fast-beating hearts of the manors they had left, the anxious waiting wives and children, and how it would be when they got home, free and safe. The King had said so.

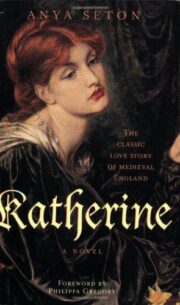

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.