Cob will tell him who we are, she thought. And that will be the end. But the little flaxen-headed outlaw did not speak. He cast a slanting look at Katherine, and busied himself with chopping off the carved emblems on the mantel.

"You then!" The tiler rounded on Blanchette, and drew back startled. Almost he made the sign of the cross, the crop-haired girl had so strange a look.

She had lifted a fold of her skirt and dabbled with her fingers in the stains made by the friar's blood, and she was smiling. Smiling as one who knows a sly secret that will confuse the hearer.

"Who are ye, child?" shouted Wat, but more gently.

Blanchette raised her head and gazed behind the tiler towards the shattered window, where drifts of smoke and flying sparks blew past.

"Who am I?" she said in a high, sweet, questioning tone. "Nay, that, good sir, I must not tell you."

Her eyes moved unseeing over the faces of the other men, who had turned to watch. "But I can tell you who I'll be" She nodded three times slowly, and she laughed low in her throat.

Wat swallowed. The men behind did not stir, their mouths dropped open and a shivering unease held them.

"Why, I shall be a whore - good sir," cried Blanchette in a loud voice, "like my mother. A murdering whore - mayhap too - like my mother!"

She gathered up her skirts in either hand as though she would make them all a curtsy. The men gaped at her. Like quicksilver she whirled and ran out of the chamber. She stumbled on the friar's dismembered headless body in the passage, then sped on swift as light to the Great Stairs.

"Stop her!" screamed Katherine, dashing forward with her arms outstretched. "Blanchette!"

Jack Maudelyn snatched out his hand and grabbed Katherine by the flying end of her coif. He jerked her back so violently that she fell. Her head hit the tiles. A thousand lights exploded behind her eyes; then there was darkness.

The tiler stared down at the woman who lay crumpled, barely breathing, on the tiles. He stared at the door through which the girl had fled. He looked at the weaver's wry-jawed face. And he shrugged.

"By the rood, I vow they've all gone mad here in this accursed place," he said. "Well - come, lads. Get on wi' it. Where's a torch? Someone carry the woman out. Who'er she be, I'll not leave her here to be roasted."

CHAPTER XXV

Across the Strand from the Savoy's gatehouse, there lay an open field that was part of the convent garden belonging to Westminster Abbey. Two of Wat Tyler's men carried Katherine there and dumped her on a grassy bank near a little brook, before dashing off to join their fellows who were streaming out of the burning Savoy, some heading for Westminster, where they would break open the Abbey prison, and many back towards the City.

Cob o' Fenton had followed the men who bore Katherine out of the Savoy and watched from afar as they laid her down. After they ran off, he stood irresolute by the roadside, tugging on his lank tow-coloured forelock. He glanced to his left where Katherine's skirt showed as a splotch of darker green against the grass; his eyes shifted to the disappearing bands of rebels.

The Lady of Kettlethorpe was mayhap dying there in the field. Well, let her then! Cob thought with sudden vigour.

What if it was her negligent order that had freed him from the stocks and given him back his croft? What good was that when her steward still exacted the heriot fine overdue from Cob's father's death? - the one ox he owned, and was fond of; company for him that ox had been, since his wife had died in childbed. Then there were the other fines - no end to them: no merchet, leyrewite; tithes to the church, "love-work" - and now the poll tax.

"Phuah!" said Cob and spat. He fingered the branded F on his cheek - fugitive, runaway serf, outlaw. Ay, and if he could escape recapture by his own manor lord for a year, he would be legally free. But she could still catch him. Cob glanced again towards Katherine. She could have him dragged back to the manor, and the punishment this time would be far worse than stocks and branding. Cob's watery, white-lashed eyes stared down at the Strand paving-stones, he gnawed at an itching fleabite on his finger, when suddenly he jumped and gasped, jerking his head up to look at the Savoy.

An explosion had thundered off behind the walls. A sheet of flame shot up as high as the spire on the Monmouth Tower, where the Duke's pennant still fluttered. The Outer Ward was not yet all afire.

Cob ran back off the road and clapped his hands to his ears, while another explosion rocked the Savoy, and another. A zigzag crack shot down the Monmouth Tower like black lightning. The tower wavered, seeming to dance and sway like a sapling in the wind, it buckled in the middle, and fell with the rumble of an earthquake, in great white clouds of dust and flying stone. Half of the Savoy Strand wall caved in beneath the fallen tower, and the gap filled in at once with raging fire.

Cob ran farther back into the field and, stumbling, fell to his knees. Above the roar and crackle of the fire he heard muffled shrieks, demon-like wails for help, different from the screaming whinnies of the terrified horses in the stables.

It was some thirty of the Essex men who shrieked. They had escaped Wat's eye and returned to the cellars and the wine casks, having found a tunnel to the Outer Ward and being sure that they had time to reach it before the fires got too hot. But Wat's men had flung into the Great Hall the three barrels of gunpowder, and the falling of the tower had trapped the rioters in the cellars beneath. It would take long before the fire ate downward to them through the stone roofing of the cellars, but there was now no way out.

"God's passion," whispered Cob, crossing himself as a deluge of flying sparks fell on him. He scrambled up and took to his heels across the field. He had quite forgotten Katherine, but she lay across his path.

He stopped, and seeing that sparks had fallen on her wool gown and were charring round smoking holes, he reached down and brushed them off. She lay on her back, her face like the marble effigies he had seen in Lincoln Cathedral. But she breathed. He saw her breasts move up and down.

And Cob, pinching out a spark that still smouldered, saw at her girdle the purse with her blazon. Through Cob's uncertain heart there struck a strange feeling. He stared down at the Swynford arms - three yellow boars' heads on the black chevron. These arms meant home. They were fastened on the manor gate, they swung on the alehouse sign. They meant the fealty that his father had loyally given to Sir Hugh Swynford, and to Sir Thomas before that. They meant the warm smell of earth and ox in his little hut, they meant the mists off the Trent, the candles in the church on holy days. They meant the companionable grumbles of his fellow villeins in the alehouse on the green, and they meant the old stone manor where he himself had done homage to Swynfords - homage to this very woman who lay flat and helpless on the grass.

"Lady!" Cob cried, slapping at her cheeks and shaking Katherine. "Lady, for the love o' God, awake!"

Still she lay limp, and her head fell back when he released her. She was tall, and he undersized and puny. He could not carry her. He took her by the feet and dragged her towards the brook, then, cupping his hands, dashed her face with water, crying, "Lady, wake, wake!" pleading with her. "Lady, I must leave ye here an ye not wake soon. For sure ye must know that? Ye'd hardly think I'd cause to burn up wi' ye, now would ye? Tis far from Kettlethorpe we are, lady, and I've all but won my freedom. Ye must know that don't ye?"

She did not move. Cob in desperation pulled at her until she rolled into the little brook. He held her head just above the water, and nearly sobbed with relief as she opened her eyes and shuddered. "'Tis cold," she whispered. "What's so cold?" She moved her hands in the flowing water, lifted them and stared at their wetness.

"Get up, lady! Up! We must hasten or I vow 'tis not cold ye'll be." He hoisted her by the armpits and Katherine slowly rose, dripping, from the brook and stood on the bank, swaying, while Cob held her. She looked down at his matted flaxen hair and the F brand on his cheek, but she did not quite remember him - someone from Kettlethorpe. She turned and stared at the immense roaring furnace across the Strand. A puzzling sight.

"Come! Can't ye walk?" cried Cob impatiently, propelling her along the field. She moved her feet forward, leaning on him heavily. Cob saw that her wet robe clung to her legs and impeded her. He drew his knife from its sheath and cut her skirt off just below the knee. She watched him in vague surprise, then, bothered by her wet hair that flowed loose, she wrung the water out of it and started to braid it.

"No time for that!" cried Cob. "Hurry!"

The flames now licked through the gatehouse; the lower prongs of the raised portcullis began to smoulder. The wind blew towards them and bore charring embers with the smoke.

"Where are we going?" Katherine said, while obediently she tried to hurry. The sick giddiness behind her eyes was passing, though her head ached.

"Into town," said Cob, though he didn't know what he was going to do with her. As soon as he had got her beyond the reach of the fire, he could dump her on some convent, of course, but he knew little about London.

"Oh," said Katherine. "I've good friends in town. The Pessoners in Billingsgate. Master Guy came yesterday to tell me about the rebels. Are we going to the Pessoners?"

"Might as well," said Cob, relieved.

He dragged her along until they came to St. Clement Danes. The Temple was burning on the Strand ahead of them. He had forgotten that. "Have to go up there, I think." He pointed up the hill towards Holborn, and turned up the footpath through Fickett's field. "Road's blocked here."

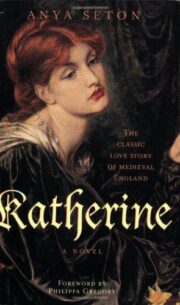

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.