Eventually they turned their attention to more practical matters. Kit told Julia how Aunt Lucy and Harry Douglas had collaborated together to pass on the news about Dominic Brandon’s marriage, and Kit had set off immediately from Dorset to travel to Norton Place.

“About ten days ago, James Lindsay confronted his cousin Patrick about the connection with Dominic Brandon, and Patrick revealed many details about the distribution network for contraband that Dominic had been organising. Frank Jepson was caught by the revenue men a few days later as he landed with a large cargo of contraband at the bay near Morancourt. I wrote to your aunt, and she passed that information on to Emily Brandon, who told the earl and countess.”

It was quite half an hour later when there was a firm cough in the doorway, and they both turned around to see Harry Douglas and Aunt Lucy standing side by side, regarding them with expressions of amusement and affection.

“Well, my dear,” said her aunt, “are you still going to return La Passerelle to Mr. Douglas?”

“No, Aunt,” said Julia meekly, “for Kit has told me that the book belongs to both of us from now on.”

The History Behind The Story

Historical Fiction

The term “historical fiction” is usually applied to a novel set in any period between the Dark Ages (before Christ) and the years immediately following the Second World War. The Historical Novel Society was founded in England in 1997, at a time when historical fiction was rather less popular than it is now, by a group of enthusiasts who volunteered to review novels being published on historical subjects.

As a keen reader of historical novels, I joined the Society in its early days, and it has continued to prosper with more and more readers, authors, publishers, and agents from the UK, and more recently from the US, becoming members. Over 100 volunteers now review about 800 books that have been published in the English language each year for the Society. Harper Collins authors like Tasha Alexander, Suzannah Dunn, Nicole Galland, and Robin Maxwell have all pleased readers with their novels about particular times in history.

Regency Romances

Although I enjoy reading novels set in all different periods of history, I seem to return most frequently to those often described as Regency Romances, which are set in the early 1800s, a time originally immortalised by the English author Jane Austen, whose six novels remain as popular now as they were in the century when they were written. She surely would have been amazed by the “Jane Austen industry” which has prospered during the past few decades through books, TV series, and films, and in particular the enduring enthusiasm of readers for her most enigmatic hero. My novel Darcy’s Story was written following the considerable success of the BBC TV series based on her bestloved book Pride and Prejudice. More recently, Cassandra & Jane, by Jill Pitkeathley, has delighted Jane Austen’s fans.

At its simplest, a Regency Romance takes place in a “gilded cage,” where a handsome hero and an attractive heroine move through grand stately homes to their destiny, apparently unaffected by the realities of everyday life.

But to me, the Regency period in England was more interesting than that. Sufficiently remote from the present day to be intriguing, and yet recent enough for there to be numerous written records of the changing patterns of life at that time, one can see the beginnings of what came to be known as the industrial revolution, the introduction of more sophisticated financial systems and the beginnings of a more emancipated life for educated women, all set against the backdrop of the war with Napoléon in the early years of the nineteenth century.

So the author of a Regency Romance has a choice. One is to take the simple route in developing the story within a “gilded cage,” and there are very many successful examples of that approach. The other option, and my preference, is to set the novel in a more realistic context, leading the reader through the way the world is changing around the characters as they approach their destiny.

The interaction between the different personalities in a family holds a particular interest for me. In my novel, the middle daughter, Sophie Maitland, took after her mother, Olivia, in being determined and irrepressible, running at everything in life at full-tilt, and could be very thoughtless. Her elder sister, Julia, also inherited her mother’s determination, but otherwise was a much calmer person, like her father, as well as being sympathetic and practical. The ideal “partners in life” for each of the sisters are therefore very different, and their stories are likely to develop accordingly. Where a personality is less clear-cut, as with the youngest sister, Harriet Maitland, there may appear to be more options, although most of her character would already have been formed when she was much younger.

Life in the Early 1800s

During the Regency period, the divisions between social classes began to ease, although the life of titled families and the gentry was still controlled by rigid formalities. Improved methods of cultivation, husbandry, and the use of simple machinery were pioneered by wealthy farmers such as Thomas Coke of Norfolk, which led to higher crop yields, healthier animals, and increased incomes for the landed gentry. The extra food produced also allowed for a significant growth in the country’s population.

The rise in the size of the population in England by the early 1800s provided not only more young men and women to work in the new factories and mills, especially in the north of England, but also a greater number of people available to be servants in the wealthier households. Although they were sometimes abused by their employers, recent research confirms that servants working in stately homes were likely to live much longer than if they had been employed in factories or remained in a farming job in the countryside.

In the grandest families, such as the Brandons in my novel, the children might well have much closer emotional ties with the servants who looked after them than they did with their parents, who they might have seen very rarely. That seems to have been the situation for Dominic Brandon and Annette Labonne, who had been a nurse to the two sons of the Earl and Countess of Cressborough.

Indeed, servants often knew a great deal about what was happening in the privacy of the household. In my novel, Julia Maitland’s widowed aunt, Mrs. Lucy Harrison, sends her maid Martha away when they travel back to Julia’s home in Derbyshire, so that she cannot tell Julia’s family anything about what happened during their stay in Dorset with Mr. Hatton.

It is not difficult to see why a wealthy young man like Dominic Brandon, who might not know his parents very well, would decide that he did not want to live at home in the country with them. He preferred to waste away his time in London with his friends, trying to live on his allowance from the Earl whilst gambling, drinking, and pursuing young women of the commoner sort, especially since that was the example that had been set by his father.

However, not everyone was like Kit Douglas in my book or Jane Austen’s brother Edward in real life, hoping to inherit the house and estate of a wealthy and childless relative. Many young gentlemen served in the army or navy, at least for a few years. The elder son of a landed family could expect to inherit the estate, but his younger brothers might need to continue to remain in the army or navy or elsewhere in the longer term. If they did not choose a military or naval life, the Church, or, to a lesser extent, the law were amongst the few respectable options for employment open to them. But, however socially acceptable an occupation, a young man serving in the army or Royal Navy risked injury during the war with Napoléon, as was the case with Kit Douglas, or at worst might be killed, as happened to Julia Maitland’s elder brother, David, and Sir James Lindsay, the father of Kit’s friend.

The choices available to young ladies of quality were much more limited. If they were wealthy with a handsome dowry or the sole heiress to a great estate, they were not likely to lack suitors keen to marry them. But when, as in the case of the Maitland sisters, the family estate was likely to pass to a distant relation on the death of a father or brother, the situation could be much more precarious. A very attractive young woman, such as Jane or Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, might be sought-after because of her looks, but the lack of a respectable dowry could mean that the only viable options for a young girl might be to become a dependant helping the family in the home of a wealthy relation, or to go and work as a governess to the children of another family.

Thus Olivia Maitland in my novel was driven not only by her social ambitions for her eldest daughter to marry into a titled family but also by her concern for what the alternative might be for Julia’s future. In some ways being a wealthy but childless widow, like Julia’s Aunt Lucy (or the late Mrs. Hatton, godmother to Kit Douglas in my book), was the best situation of all, putting her in control of her own money and property, and free to do as she liked with both.

Inventions such as the spinning mule and power loom and the use of water wheels to drive machinery led to craft industries, such as weaving, being transferred from the rural homes into mills in both rural and urban locations. Other technical inventions aided the development of mining and other industrial enter prises, but their introduction sometimes led to riots and loss of life if the installation of even one machine deprived several men of their jobs.

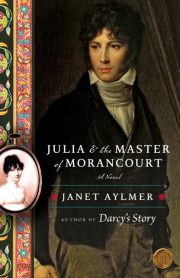

"Julia and the Master of Morancourt" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt" друзьям в соцсетях.