“Now,” he said to Julia, “if we went this way, we would go through the village, but the other way—let’s try that.” He handed her up into the curricle, and then took his own place and turned the horses along the other track. Soon they could see the sea on their right, and in the distance the roofs of some farm buildings straight ahead of them. Suddenly, Mr. Hatton pulled hard on the reins and brought the curricle to a halt.

“What is it?” said Julia, startled by the abrupt action.

“Look down there, Miss Maitland,” said Mr. Hatton very quietly so as not to be overheard by the groom standing on the footplate behind them. He pointed to the east towards the sea, and she saw that there was a well-worn route leading from the track they were following across a field down into a side valley.

“I wonder where that goes?” said Julia quietly in reply. “It looks surprisingly well used.”

“Not to the village, so maybe to the seashore. But,” he said, looking down at his well-pressed breeches and Julia’s neat dress and shoes, “neither of us is dressed for hill-climbing or mountaineering this afternoon. We can look another day, or at least I can,” and without further comment he took the curricle on and pulled up the horses at the end of the track, which stopped short of some more farm buildings by about a hundred yards. There again, there were signs of foot traffic from the end of the track towards the old structures.

“Do you think that we have the beginnings of a mystery here?” Julia whispered.

“Perhaps, or it could just be some of the labourers using the buildings as a shelter in wet weather,” he replied in an undertone, and he turned the curricle with a sure hand on the reins back

onto the route that they had come, and on past the farmhouse again towards Morancourt.

On Wednesday morning, the weather showed a partly blue sky, although a stiff breeze was developing off the sea beyond the crest of the hill. After settling Aunt Lucy in the salon with the help of Martha and Mrs. Jones, Julia fetched her warm white pelisse and her old boots and met Mr. Hatton at the front door, ready to walk with him across the park to the view that he had promised her beyond the hill. He was wearing a long black cloak with several capes over his day attire, as a protection from the wind.

As they made their way together on a rough track alongside a boundary wall leading towards the hill, Mr. Hatton suddenly said, “Do you know Dominic Brandon well? I have heard many things about him—not all of them good. Is your mother very anxious that he should be a serious suitor for you?”

“Perhaps. He is not the only young man she favours. I really prefer not to think about him.”

“There are many other young gentlemen in Derbyshire who you might prefer?”

“Do you include your brother in that?” Julia replied.

“Jack? No, I cannot see you marrying him. Chalk and cheese, that would be. But, if that did ever occur, I would not be able to watch you living together.”

That is very close to making me a declaration, thought Julia.

“I hope, Mr. Hatton, that you are not trying to organise my life for me?” she replied, trying to speak lightly.

“I’m afraid that I cannot avoid some degree of self-interest in the matter, Miss Maitland.”

She had been looking straight ahead during this exchange, but ventured a sideways glance, to find that his green eyes were regarding her with an expression that she could not quite fathom.

“I do wish that I had known you for longer, Miss Maitland, as you do the Brandon family. I sometimes find it very difficult to make out what you might be thinking.”

“I have not sought to deceive you, sir. There are few people in the world, I have found, whom I can really rely on and trust—my father is one, and my youngest sister, Harriet, another. And I believe that I have trusted you to tell me the truth from the beginning of our acquaintance. That gives so much ease, does it not?”

He did not reply and, after a short interval of silence, she went on. “Emily Brandon is also someone I can rely on, although I sometimes find that she is easily diverted when I am trying to get her to take matters seriously.”

He laughed out loud. “I agree, for I noticed in Bath that she always said exactly what she thought, whoever was around to hear her. But she is a pretty girl with a pleasant personality, and certainly attracted a great deal of attention from young men wherever she went.”

Julia was annoyed with herself to feel a tinge of jealousy at his comment, which was quite irrational, since everything he had just said about Emily was true and confirmed her own perceptions.

Then he added, “But you are unique, Miss Maitland, in my experience. I have never met anyone in my life before whom I have liked and admired so much.”

Julia blushed to the roots of her hair and could not think of anything to say.

During this conversation, they had been walking closer and closer to the crest of the hill. On their right there were ridges at intervals across the slope of the ground, creating narrow pathways.

“What are those, Mr. Hatton?”

“Lynchets—they are called strip lynchets. Some people say that they arose over time by ploughing the ground. Others take the view that they were created deliberately many years ago to prevent the farmers and their stock from slipping down the slope and to reduce the erosion of the soil. They are quite common in this part of Dorset.”

“Some of the ground above the edge of that lynchet looks as though it has been ploughed recently,” observed Julia, “so perhaps they are still in use.”

They continued to walk further up the hill for a few more minutes. Then, just before they got to the top of the slope, Mr. Hatton asked her to stop walking.

“Now, Miss Maitland, please trust me. Shut your eyes and allow me to take your hand and lead you these last few steps.”

Julia did as she was bid, and the touch of his hand in hers made her pulse race as he led her slowly forward and then stopped again.

“Now you may look.”

Julia opened her eyes, expecting to see the sea. And she could, some way in the distance, perhaps two miles away. But what really caught her attention was what was in the foreground.

For there, about a hundred feet in front of her, was a ruined building built in the same golden yellow stone as Morancourt, glowing in the sunshine. On one side there was a circular building like a castle keep, with parts of the top broken and missing. Behind it, a line of lower outbuildings went in the direction of the sea.

On the other side, there was another substantial tall L-shaped building. To the left, she could see some damaged stained-glass windows with arched tops set in the lower part of the rougher stone wall and, on the right, there were straight walls pierced by arrow slits here and there. But between the keep and that building there was an arch, with a small central section missing. It was the passerelle that she had seen in the library picture at Morancourt.

Julia exclaimed with delight and turned to find him smiling at her with such a happy expression that it made her heart sing.

“Do you like the abbey, Julia?” he said.

And she had replied in the affirmative before she realised that he had used her Christian name and, from his expression, he had himself become aware of that at the same moment.

He took her hands in his, without saying anything, and then very gently took them up to his lips and kissed them, before releasing her fingers. Julia found herself almost overcome by the emotion that she felt at the pleasure of his touch, the urge to reciprocate, and his silent confirmation of how he felt about her. She could not trust herself to look at him, but stood by his side looking at the view and thinking her own thoughts for quite some time.

At last, when she was confident of some control over her voice, she ventured, “Can you tell me something of the history of the abbey?”

There was a pause before he replied, and Julia wondered if he, too, was finding it very difficult to control his emotions.

“A little. The site was originally occupied by an old castle—nothing grand, but a stronghold nevertheless—hence the circular keep. Later the site was given to an order of French monks, who came from Morancourt, and they extended the buildings to create their abbey, and lived happily enough here for two hundred years. But in the 1530s, King Henry the Eighth dissolved and closed all the monasteries, so that he could raise money from selling their buildings and land. Either that, or the abbey and the village were raided for slaves.”

“Slaves?” exclaimed Julia.

“Yes. Pirates from northern Africa regularly raided coastal villages in northern Europe for many years—Spain, Portugal, France, Ireland, and other countries—to find white slaves to be taken back.”

“I knew nothing of that.”

“Many people have forgotten, but it is said that thousands of men and women were taken over the years from the coastal villages in Devon, Cornwall, and Dorset, and that the trade continued in some areas until the early part of this century.”

“What would have happened to those unfortunate people?” said Julia, shivering at the thought.

“Some became labourers, perhaps in quarries, or building palaces for the rulers in cities such as Tunis. Or they were taken to be galley slaves, condemned never to set foot again on land, and the women were sought after as concubines. The wealthy amongst them were held for ransom. Whether the monks were taken as slaves, or whether the abbey was sold off by the King in the sixteenth century, local history does not say. But the monks did abandon the abbey here at Morancourt, and eventually the manor house was built further away from the coast, out of sight of the sea.”

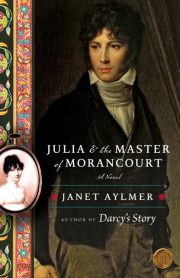

"Julia and the Master of Morancourt" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt" друзьям в соцсетях.