“Mrs. Jones, you will let me know if you need to send for anything from Beaminster or Bridport?”

“Of course, Miss Maitland, but I should have everything that we need here.”

Julia took Martha firmly by the arm and out of the kitchen to a quiet corner in the corridor.

“Did you know that Jem was working in this area, Martha?”

“No, Miss.”

“Why did he not acknowledge you as his sister? Do you know what work he’s doing?”

“I don’t know, Miss.”

“Very well,” said Julia, thoughtfully. “It might be best if you say nothing about this at present to Mrs. Harrison. I will make inquiries, but only of Mrs. Jones. You should not do anything yourself.”

“No, Miss,” said Martha, her eyes looking remarkably like those of a frightened rabbit as she darted off upstairs.

Julia debated with herself whether to mention this incident to Aunt Lucy, or to Mr. Hatton, but decided that it would be better to do so when she knew more.

After Aunt Lucy had gone to bed that evening, Julia went back to the kitchen and found Mrs. Jones supervising the maids, who were clearing up the dinner plates and scouring the cooking pans.

“Mrs. Jones, do you know when Mr. Whitaker first employed that young man?”

“No, Miss Maitland. My husband said that he worked on the farm, although I haven’t seen him around myself. Most of the farm workers come from the village, or live in one of the estate houses owned by Mrs. Hatton—I mean young Mr. Hatton now, of course.”

“And his name is Jem, I think you said?”

“That’s what my husband told me when he carried him into the kitchen. He’s taken him back to the village now on the cart.”

Julia thanked her, and left the matter there.

On the following morning, Julia could not find Mr. Hatton anywhere. Neither Mrs. Jones nor Aunt Lucy could tell her where he was. Julia fetched her walking boots, put on her drab pelisse, and decided to set out along the track towards the farm buildings. She was within a short distance of her destination when she was surprised to see Mr. Jones running towards her.

“Miss Maitland,” he said, trying to catch his breath at the same time, “please come with me. It’s Mr. Hatton. We had been walking together along the path, and he was ahead of me as it narrowed along a bend. Then I heard shouting and found that the smugglers had pushed him to the ground before they disappeared into the woods!”

He would not explain further, and urgently pressed her to go on with him. Just before they got to the farm buildings, on the last bend in the track, he suddenly swerved into bushes on the left, onto a well-worn path concealed from view on both sides.

After about fifty yards, they came upon Mr. Hatton sitting on the ground with his clothes dishevelled and rubbing his head as though badly dazed.

“Here’s Miss Maitland, sir,” her companion said. “You just walk slowly back with her, Mr. Hatton, and you should be fine.”

Mr. Jones helped him to his feet. Then he doffed his cap to Julia and left them, walking quickly in the direction of the sea.

Mr. Hatton looked at Julia ruefully and said, “I told you to be careful, but did not take my own advice!”

“What happened?” said Julia, relieved that he seemed to be speaking sensibly.

“We were walking along the track—Mr. Jones and I—and decided to take this side route, so that we would not be seen. Then three fellows whom I have never seen before came upon me and pushed me aside very roughly, shouting and threatening me. One said in French that I should say nothing about having seen them here. I was interested that neither of the other two seemed to have a local accent.”

“Do you speak French fluently?”

“Quite well—my mother had a French governess when she was young, and she in turn taught me. Certainly, I speak French much better than I do Spanish.”

“You may have been lucky—the incident could have been much worse!”

“Yes, you are right. I said nothing to them, and I don’t think they had any idea who I was. As you may note, I am not dressed as they might have expected a landowner to be.”

“No, I see what you mean.” Julia laughed, looking at his lack of a coat or neckcloth, and the plain cut of his leggings with a simple white shirt.

“Mr. Jones was walking some distance behind me because there was no width on the path for us both at that point, so they did not catch sight of him before they took another route to get away.”

“Do you wish me to support you as far as the house?” Julia asked.

“No, best not,” he replied, “though I am obliged to you for your offer. I believe that I am just winded, and shall be fine in a short while.”

So they walked slowly back together to the manor house, where Mr. Hatton was able to enter unobtrusively and go up to his room without being observed.

Later that day, Julia went to find Aunt Lucy. “I was thinking of going into Beaminster now with Martha, dear Aunt. Mr. Hatton has offered me the use of his carriage. Do you have any commissions that we can get for you?”

“Well, my dear, Mrs. Jones was mentioning the Blue Vinney cheese to me, which I am told is made locally from skimmed milk and is very palatable. Can you go to the grocers for that whilst you are in the town? And I would fancy some local bread, and perhaps some lemons for those desserts that you were talking about to Mr. Hatton—the ones from Derbyshire.”

“Of course, Aunt,” said Julia.

On the journey with Martha beside her, and now that she knew what to look for, Julia could see the many fields of flax and hemp alongside the road as they travelled towards the town. Where there were streams in the fields, she could see the dams sometimes made across them to form ponds, which Mr. Hatton had explained were used to soak or “ret” the hemp and flax fibres to soften them. She remembered that he had told her that one of the main products manufactured in Beaminster itself was sailcloth. Like rope, that material was also made from hemp.

The coachman let them down in the corner of the square, saying that they would find Pines, the grocers’ shop, along the road on the right in Fleet Street, and he agreed to be back with the carriage to pick them up in about an hour’s time.

Pines proved to be a delightful emporium, with a tall bow-fronted window on each side of the stone entrance porch, and the date of 1780 engraved over the main door. Inside, several shop assistants were busy behind the long mahogany counter, serving customers and measuring out flour, sugar, and spices from the jars on the high shelves fixed to the wall behind them. As Mr. Hatton had told her, the range of goods seemed to be as great as in many much grander establishments in Bath and London. Julia chose the various purchases sought by Aunt Lucy, paid for them, and gave them to Martha to carry.

It was after they had returned to the square and were looking in the windows of the other shops that Julia glanced across the street and saw Patrick Jepson alighting from the Bridport coach in front of the White Hart public house. Waiting for him on the paved sideway was the man she had been told might be his half brother, Frank. As she watched, the two walked away together and turned down the road past the Eight Bells Inn leading to St. Mary’s Church, and Julia lost sight of them just as Mr. Hatton’s carriage arrived for the return journey to Morancourt.

Nine

The next afternoon, Julia went with Mr. Hatton to visit the Whitakers’ farmhouse. This time, she had declined his invitation to take the reins of the curricle, on the grounds that she had no familiarity with the route.

The farmhouse was situated much nearer to the sea than the manor itself, and lay low in a fold of the hills, so that the coast was not visible as they alighted and walked towards the front door. The house was built in roughly cut local stone, with the walls partly covered with a green climbing plant. It seemed that Mrs. Whitaker might have been expecting their arrival, for she opened the old oak door almost as soon as they had knocked.

The ceilings inside were low, and Julia guessed that the house was the same age as the older part of the manor house at Morancourt. The sitting room smelt rather damp, and the paintwork and some of the floorboards were worn and in need of attention. The kitchen and scullery were small and dark, so that Julia did not realise for some moments that there were two small children there. The elder, a girl, she recognised from their visit to the school. The younger, a small boy, was playing on the floor with a little puppy.

Mrs. Whitaker answered Julia’s unspoken question. “My mother looks after him in the village in the mornings whilst I teach at the school, Miss Maitland. Fortunately he is very good.”

After looking around the rooms on the ground floor, Mr. Hatton commented, “Well, Mrs. Whitaker, I am very glad that I came, for it is clear that we need to have some work done here to make your kitchen brighter and easier to use. If you would like to ask Mr. Whitaker to take some measurements, I shall consult Miss Maitland, and we will make some suggestions to discuss with you both.”

Mrs. Whitaker was delighted and asked them to look around the upstairs rooms as well, where Mr. Hatton made more notes whilst Julia talked to Mrs. Whitaker.

“I thought that the children in the school were very neatly dressed.”

“Thank you, Miss Maitland. Some have only one set of clothes, but most of the boys were given new neckerchiefs recently by a man in the village, which made them feel very smart!”

Julia nodded, and Mr. Hatton paused for a moment whilst writing his notes to listen to this remark. After a few more minutes, they said a cordial farewell to Mrs. Whitaker and left the house.

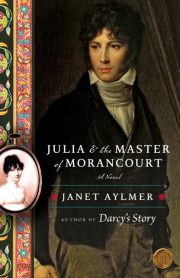

"Julia and the Master of Morancourt" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Julia and the Master of Morancourt" друзьям в соцсетях.