It was time she took a greater interest in matters of her own life, said Mrs. Douglas. Vere, who had anyway needed to go to London, volunteered to accompany her. They also brought along Mrs. Green, who would see to it that Mrs. Douglas was comfortably put up and meticulously looked after.

And now Mrs. Douglas dozed in their rail compartment, her weight against Vere’s arm as insubstantial as that of a blanket.

Memories surfaced of her daughter sleeping next to him on the train. He remembered his resentful bewilderment that he could have been drawn to someone of such questionable character. His intellectual self had yet to recognize what a deeper, more primal part of him already sensed at first sight: her integrity.

Not integrity in the sense of unimpeachable practice of morality, but a personal wholeness. Her trials under Douglas had not left her unmarked, but neither had they lessened her.

Whereas he had been both scarred and diminished.

He had always used the language of Justice to relate to his work. True justice was motivated by an impartial desire for fairness. What underlay his entire career had been anger and grief: anger that he could not punish his father, grief that he could not bring back his mother.

That was why he derived only negligible satisfaction from even his greatest successes: They reminded him of his impotence in his own life, of what he could never accomplish.

And that was why he had been so livid at Freddie: part of it had been envy. By the time he had spoken to Lady Jane, his father had been three months dead. And yet Vere’s obsession had only grown. He could not understand how Freddie could let go and move on, while he remained stuck between the night of his mother’s death and the night of his father’s.

Thirteen years. Thirteen years of chasing after what could never be had in the first place, while his youth fled by, his erstwhile ambitions lay forgotten, and his life grew ever more isolated.

A single snore in the compartment brought his attention back to his fellow traveler. Mrs. Douglas fidgeted, then slept on. On the way to the rail station, she had shyly confided that before she’d met him, she’d already seen him in a laudanum-fueled dream—he’d rather wondered what she’d made of his presence in her room. One day, when he had his life in order, he would tell her the truth and apologize for frightening her.

She fidgeted again. Vere studied her: the cheeks, still pale, but now with a whisper of color; the neck, still thin, but no longer sticklike. When he’d first met her, he’d assumed her permanently broken. She had instead proved herself a dormant seed that needed only a less hostile environment to come alive.

He turned to the window again. Perhaps he too was not as permanently broken as he’d believed.

This time, instead of using his own key, Vere rang Freddie’s bell.

He was shown into Freddie’s study, where Freddie was checking a book of rail schedules, his finger moving down a column, searching for what he needed. Freddie looked up and dropped the book.

“Penny! I was just coming to see you.” He rushed up to Vere and embraced him anxiously. “If you arrived fifteen minutes later I’d have left to Paddington Station already. I heard the most bizarre rumors this morning: Lady Vere’s uncle escaped jail and abducted you—and you had to fight for your life. What happened?”

The words were on Vere’s lips—Oh rubbish, don’t people know how to gossip properly anymore? I didn’t have to fight for my life. I subdued that toothpick of a man with one finger—and an expression of thick satisfaction was already rising to his face.

The temptation to fall back on the idiocy he played so expertly was enormous. Freddie didn’t expect anything else of him. Freddie had long become accustomed to the idiot. They were still brothers—loving brothers. Why change anything at all?

He crossed the study, poured himself a measure of Freddie’s cognac, and tossed it back. “What you heard was a lie I told,” he said. “Mr. Douglas had abducted Mrs. Douglas, in truth. But once we rescued Mrs. Douglas, we decided that it was better for her to go home to recuperate rather than talk to the police. So I took Mr. Douglas to the police station and made up a cock-and-bull story.”

Freddie blinked. And blinked again several times. “Ah—so, is everyone all right?”

“Lady Vere has some bruises; she won’t be able to receive callers for a few days. Mrs. Douglas had quite a fright, but she came with me today and is currently enjoying herself at the Savoy Hotel. Mr. Douglas, well, he’s dead. He decided that he was better off swallowing cyanide than taking his chances in court.”

Freddie listened attentively. When Vere had finished speaking, he looked at Vere for some more time, then gave his head a small shake. “Are you all right, Penny?”

“You can see I’m perfectly fine, Freddie.”

“Well, yes, you are in one piece. But you are not acting like yourself.”

Vere took a deep breath. “This is who I’ve always been. But it’s true that sometimes—most of the past thirteen years, in fact—I haven’t acted myself.”

Freddie rubbed his eyes. “Are you saying what I think you are saying?”

“What do you think I’m saying?” Vere asked. He thought he’d made himself clear, but Freddie hadn’t reacted as he’d expected.

“One moment.” Freddie reached for a small encyclopedia and opened it to a random page. “In what year was the first plebeian secession?”

“In 494 B.C.”

“Dear Lord,” Freddie muttered. He turned the encyclopedia to a different section, then looked up with an expression of such singular hope that Vere’s stomach wrenched. “Who were Henry the Eighth’s six wives?”

“Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour, Anne of Cleves, Catherine Howard, and Catherine Parr,” Vere said slowly. He could have recited the list much faster, but he dreaded finishing answering the question.

Freddie set down the book. “Do you support women’s suffrage, Penny?”

“New Zealand granted unrestricted voting rights to women in ’ninety-three. South Australia granted voting rights and allowed women to stand for Parliament in ’ninety-five. The sky hasn’t fallen in either place, last I checked.”

“You have recovered,” Freddie whispered, tears already coursing down his face. “My God, Penny, you have recovered.”

Vere was suddenly crushed by Freddie’s embrace.

“Oh, Penny, you have no idea. I have missed you so much.”

Tears rolled down Vere’s cheeks: Freddie’s joy, his own shame, regret for all the time they had lost.

He pulled away.

Freddie did not notice his distress. “We must tell everyone right away. Too bad the Season is finished. My goodness, won’t everyone be in for a genuine shock next year. But we can still go to our clubs and make the announcements. And you are not leaving town right away, are you? Angelica is up in Derbyshire visiting her cousin, but she should be back tomorrow. She will be thrilled. Thrilled, I tell you.” He spoke in such a rush his words were shoving one another out of the way. “Let me ring for Mrs. Charles. I think I have a bottle or two of champagne lying around. We must celebrate. We must celebrate properly.”

Freddie reached for the bellpull. Vere grabbed his arm. But what he needed to say stuck in his throat like wet cement. He’d steeled himself to face Freddie’s wrath, not this overwhelming joy. To speak more on the subject would annihilate the happiness that flushed Freddie’s face and glistened in his eyes.

But Vere had no choice. If he allowed himself to stop here, it would be another Big Lie between the two of them, where there were piled too many lies already.

He dropped his hand from Freddie’s arm and clenched it into a fist. “You misunderstood me, Freddie. I haven’t recovered from anything, because there was nothing to recover from. I never had a concussion. It has been my choice to act the idiot.”

Freddie stared at Vere. “What are you saying? You were diagnosed. I talked to Needham myself. He said you suffered a personality-altering traumatic injury to the head.”

“Ask me again about women’s suffrage.”

Some of the color drained from Freddie’s cheeks. “Do you…do you support women’s suffrage?”

For some reason, the role did not immediately come to Vere, as if he were an actor who had already left the stage, stripped off his costume, wiped clean his makeup, and fallen half-asleep, and then was suddenly asked to reprise his performance.

He had to take several deep breaths and imagine strapping a mask over his face. “Women’s suffrage? But what do they need it for? Every woman is going to vote the way her husband tells her to, and we will still end up with the exact same idiots in Parliament! Now if dogs could vote, that would make a difference. They are intelligent, they are loyal to the Crown, and they certainly deserve more of a say in the governance of this country.”

Freddie’s mouth dropped open. He flushed with embarrassment. And then, as Vere watched, his expression slowly darkened into anger. “So all these years, all these years, it was just an act?”

Vere swallowed. “I’m afraid so.”

Freddie stared at him another minute. He drew back his fist. It landed on Vere’s solar plexus with an audible thwack. Vere stumbled a step. Before he could recover, another punch landed. And another. And another. And another. Until he was pinned to the wall.

He’d had no idea Freddie was capable of violence.

“You bastard!” The words exploded in a roar. “You swine! You bloody sham!”

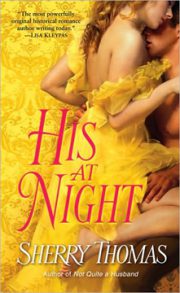

"His At Night" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "His At Night". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "His At Night" друзьям в соцсетях.