"Because you got to make a speech?" Jean asked.

"Yes, that mostly," I said.

"What's it about?" Pierre asked.

"It's about how we should be grateful for what we have, for what our parents and teachers have done for us, and how that gratitude must be turned into hard work so we don't waste opportunities and talents," I explained.

"Boring," Jean said.

"No, it's not," Pierre corrected him.

"I don't like sitting and listening to speeches. I bet someone throws a spitball at you," Jean threatened.

"It better not be you, Jean Andreas. There's plenty that has to be done around here all day. Don't get underfoot and don't aggravate Mommy and Daddy," I warned.

"We can stay up until everyone leaves tonight," Pierre declared.

"And Mommy let us invite some of our friends," Jean added. "We should light firecrackers to celebrate."

"Don't you dare," I said. "Pierre?"

"He doesn't have any."

"Charlie Littlefield does!"

"Jean!"

"I won't let him," Pierre promised. He gave Jean a look of chastisement, and Jean shrugged. His shoulders had rounded and thickened this past year. He was tough and sinewy and had gotten into a half dozen fights at school, but I learned that three of those fights were fought to protect Pierre from other boys who teased him about his poetry. All their friends knew that when someone picked a fight with Pierre, he was picking a fight with Jean, and if someone made fun of Jean, he was making fun of Pierre as well.

Mommy and Daddy had to go to school to meet with the principal because of Jean's fights, but I saw how proud Daddy was that Jean and Pierre protected each other. Mommy bawled him out for not bawling them out enough.

"It's a tough, hard world out there," Daddy said. "They've got to be tough and hard too."

"Alligators are tough and hard, but people make shoes and pocketbooks out of them," Mommy retorted. No matter what the argument or discussion, Mommy had a way of reaching back into her Cajun past to draw up an analogy to make her point.

After breakfast I returned to my room to fine-tune my valedictory address, and Catherine called.

"Have you decided about tonight?" she asked.

"It's going to be so hard leaving my party. My parents are doing so much for me," I moaned.

"After a while they won't even know you're gone," Catherine promised. "You know how adults are when make parties for their children; they're really making them for themselves and their friends."

"That's not true about my parents," I said.

"You've got to go to Lester's," she whined. "We've been planning this for months, Pearl! Claude expects it. I know how much he's looking forward to it. He told Lester, and Lester told me just so I would tell you."

"I'll go to the party, but I don't know about staying overnight," I said.

"Your parents expect you to stay out all night. It's like Mardi Gras. Don't be a stick-in-the-mud tonight of all nights, Pearl," she warned. "I know what you're worried about," she added. Catherine was the only other person in the world who knew the truth about Claude and me.

"I can't help it," I whispered.

"I don't know what you're so worried about. You know how many times I've done it, and I'm still alive, aren't I?" Catherine said, laughing.

"Catherine . . ."

"It's your night to howl. You deserve it," she said. "We'll have a great time. I promised Lester I would see that you were there."

"We'll see," I said, still noncommittal.

"I swear, Pearl Andreas, you're going to be dragged kicking and screaming into womanhood." She laughed again.

Was this really what made you a woman? I wondered. I knew many of my girlfriends at school felt that way. Some wore their sexual experiences like badges of honor. They had a strut about them, a demeanor of superiority. It was as if they had been to the moon and back and knew so much more about life than the rest of us. Promiscuity had given them a sophistication and filled their eyes with insights about life, and especially about men. Catherine believed this about herself and was often condescending.

"You're book-smart," she always told me, "but not life-smart. Not yet."

Was she right?

Would this be my graduation night in more ways than one?

It was difficult to return to my speech after Catherine and I ended our conversation, but I did. After lunch, Daddy, Mommy, and the twins sat in Daddy's office to listen to me practice my delivery. Jean and Pierre sat on the floor in front of the settee. Jean fidgeted, but Pierre stared up at me and listened intently.

When I was finished, they all clapped. Daddy beamed, and Mommy looked so happy, I nearly burst into tears myself. Graduation was set to begin at four, so I went upstairs to finish doing my hair. Mommy came up and sat with me.

"I'm so nervous, Mommy," I told her. My heart was already thumping.

"You'll do fine, honey."

"It's one thing to deliver my speech to you and Daddy and the twins, but an audience of hundreds! I'm afraid I'll just freeze up."

"Just before you start, look for me," she said. "You won't freeze up. I'll give you Grandmère Catherine's look," she promised.

"I wish I had known Grandmère Catherine," I said with a sigh.

"I wish you had too," she said, and when I gazed at her reflection in the mirror, I saw the deep, far-off look in her eyes.

"Mommy, you said you would tell me things today, things about the past."

She nodded and pulled back her shoulders as if she were getting ready to sit down in the dentist's chair.

"What is it you want to know, Pearl?"

"You never really explained why you married your half brother, Paul," I said quickly and lowered my eyes. Very few people knew that Paul Tate was Mommy's half brother.

"Yes, I did. I told you that you and I were alone, living in the bayou, and Paul wanted to protect and take care of us. He built Cypress Woods just for me."

I remembered very little about Cypress Woods. We had never been back since Paul's death and the nasty trial for custody over me that had followed.

"He loved you more than a brother loves a sister?" I asked timidly. Just contemplating them together seemed sinful.

"Yes, and that was the tragedy we couldn't escape."

"But why did you marry him if you were in love with Daddy and I had been born?"

"Everyone thought you were Paul's daughter," she said. She smiled. "In fact, some of Grandmère Catherine's friends were angry that he hadn't married me yet. I suppose I let them believe it just so they wouldn't think I was terrible."

"Because you had gotten pregnant with Daddy and returned to the bayou?"

"Yes."

"Why didn't you just stay in New Orleans?"

"My father had died, and life with Daphne and Gisselle was quite unpleasant. When Beau was sent to Europe, I ran off. Actually," she said, "Daphne wanted me to have an abortion."

"She did?"

"You wouldn't have been born."

I held my breath just thinking about it.

"So I returned to the bayou where Paul took care of us. He even helped me give birth to you. When I heard Daddy was engaged to someone in Europe, I finally gave in and married Paul."

"But Daddy wasn't engaged?"

"It was one of those arranged things. He broke up with the young lady and returned to New Orleans. My sister had been seeing him. She had a way of getting whatever she wanted, and your father was just another trophy she wanted," Mommy said, not without a touch of bitterness in her voice.

"Daddy married Gisselle because she looked so much like you, right?" It was something I had squeezed out of Daddy when he had decided to stem the flood of questions I poured at him.

"Yes," Mommy said.

"But neither of you were happy?"

"No, although Paul did so much for us. I devoted all my time to my art and to you. But then, when Gisselle became sick and comatose . . ."

"You took her place." I knew that story. "And then?"

"She died, and there was the terrible trial after Paul's tragic death in the swamp. Gladys Tate wanted vengeance. But you knew most of that, Pearl."

"Yes, but, Mommy . . ."

"What, honey?"

I lifted my eyes to gaze at her loving face. "Why did you get pregnant if you weren't married to Daddy?" I asked. Mommy was so wise now; how could she not have been wise enough to know what would happen back then? I had to ask her even though it was a very personal question. I knew most of my girlfriends, including Catherine, could never have such an intimate conversation with their mothers.

"We were so much in love we didn't think. But that's not an excuse," she added quickly.

"Is that what happens, why some women get pregnant without being married? They're too much in love to care?"

"No. Some just get too caught up with sex and lose control. You can be the smartest girl in school, the best reader, have the highest grades, but when it comes to your hormones , well, just be careful," she said.

"It doesn't seem fair," I said.

"What?"

"That men don't face the same risks."

Mommy laughed. "Well, let that be another reason why you don't let a young man talk you into something you don't want to do. Maybe if men knew what it was like to give birth, they wouldn't be so nonchalant about it all."

"They should feel the same labor pains," I said.

"And get sick in the morning and walk around with their stomachs hanging low and their backs aching," Mommy added.

"And get urges to eat pickles and peanut butter sandwiches."

"And then have contractions."

We both roared and then hugged.

Daddy, coming up the stairs, heard us and knocked on the door. "Exactly what are you two females giggling about now?" he asked.

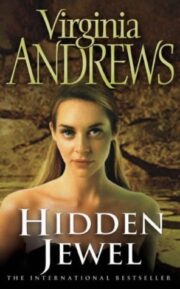

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.