"I doubt that I'll get back to that size and you just might be going to more formal affairs in the future."

"But, monsieur—"

"Please," Daddy insisted. "It's nothing compared to what you've done for me." Reluctantly, Jack took the jacket.

Before Mommy and I returned to the hospital to visit with Pierre, I said good-bye to Jack in front of the house.

"I forgot to give you back your clothes," I reminded him.

"Can't trust you city folk."

I laughed.

It was a very sunny morning without the usual haze. Everything looked brighter, cleaner, and the air was filled with the scent of flowers and bamboo. We could hear the city coming to life, the streetcar rattling, cars honking horns, someone shouting down the street, and lawn mowers and blowers being started.

"I'll see you before I start college, won't I?"

"Absolutely," he said. "Besides, you should visit your well more often, get to know her. And bring Pierre."

"I will."

We kissed.

"Safe trip," I said putting my finger on his beautiful lips and drinking in the softness in his eyes. "I'll miss you."

"Me too." He got into his truck. "I hope I don't get lost in these city streets," he complained.

"A man who can find his way around those swamp canals shouldn't have any trouble navigating the streets of New Orleans," I said.

Jack laughed. Then he put on a serious expression and gazed at me.

"I don't know if I have a right to love you, but I sure think I do," he said.

"You have more than a right, Jack Clovis. You have an obligation. You better love me."

He flashed that wonderful smile, the smile that would have to last me for some time, and then drove away.

I started to cry, but then drew back my tears and took a deep breath. I had to be strong for Mommy and Daddy. We had a long road ahead with many steep hills to climb and many sharp turns.

Two days later we brought Pierre home from the hospital. He was shaky, but he wanted to walk. I held his hand and guided him. He wanted to go out to the gardens. I knew why. He wanted to look at the tree house he and Jean and Daddy had built long ago. The doctors thought he should get as much air as he could. They said it would make him tired, at least for the first week or so. It did. He fell asleep in his chair after lunch, and I carried him up to his room.

But he was outside every morning. I spent a great deal of time with him, reading to him, playing board games, answering his questions about his illness. He went to therapy once a week and had a good checkup from Dr. Lasky, who was impressed with Pierre's physical recuperation. "The mind is far more powerful than we can imagine," he told Mommy. She was the one person in the world he didn't have to tell.

Epilogue

Two weeks after Pierre came home, Mommy decided to visit Jean's grave again. I went with her. She set out some flowers and stood gazing at the tomb, a small smile on her face as she recalled his antics and the way he threw his arms around her when he was frightened or sick or just wanted her love. But I knew why she wanted to go there. It wasn't just to remember. It was to say thanks, for she believed in her heart that it was Jean's spirit that had turned Pierre around and sent him back to us.

When Pierre was strong enough to make the trip, we went to visit Jack at Cypress Woods. Jack spent a great deal of time with him, showing him the machinery, explaining how everything worked. Daddy and Mommy walked around the neglected grounds and the house, and then we all went for lunch in Houma and ate crawfish étouffée.

A few weeks later I began my college orientation. Pierre was strong enough to return to school in September, although he was still seeing a therapist once a week. He was having a hard time adjusting to life without Jean at his side. Often I would find him off by himself, and I knew he was talking to Jean. Finally, Dr. Lefevre decided it would be good for Pierre to visit Jean's grave.

At first he resisted. I talked to him for a long time about it until he finally relented, and we all went to the cemetery with him. He just stared at the tomb and read Jean's name over and over. He was very quiet for the rest of that day, but I did see a change in him in the weeks that followed. He became more outgoing, was willing to have friends over and to visit with them. He grew taller and leaner and continued to be a very good student.

The summer never seemed to end that year. It was hot and humid right into the first week of December. Jack came to see me at college, but he was uncomfortable on the campus and was happier at the house or visiting the sights. Pierre loved him and was never so happy as when Jack visited us or we went to visit him in the bayou.

Late that spring, just after April Fool's Day, Aunt Jeanne called to tell Mommy that Gladys Tate had died. She said the family was thinking of restoring Cypress Woods.

"Paul would like that," Mommy told her. "He was very proud of that house."

"I know Pearl visits from time to time," Aunt Jeanne said. "Maybe you could come along sometime, and we could spend some time there. I'd like to hear your suggestions for fixing the place up."

Mommy told her she would think about it. She related the conversation to us at dinner.

Daddy listened and then said it wasn't a bad idea. "They don't know anything about real estate," he told her.

He knew how much Mommy wanted to be part of the restoration and made it easier for her. I was happy because that meant I would have that many more opportunities to spend time with Jack.

Something subtle began to happen to me as I made more and more visits to the bayou. In the beginning I believed my horrible experience with Buster Trahaw and my frightening time in the swamps had left me with such a bad taste for the bayou that I would never see anything pretty or pleasant about it again. But when I was with Jack and he and I walked over the grounds or drove on the back roads, it was different.

Just as I was eager to show him my city world, he was eager to show me nature, to point out the different flowers and animals. He had a Cajun guide's eye and could spot sleeping baby alligators, brown pelicans, marsh hawks, and butcher birds. I would have to stare and stare and sometimes be taken by the hand and nearly brought right up to them before I saw what he saw. Then I would nearly burst with astonishment.

I saw the bayou during every season, met many of the local people, and got to know and like them. I felt they liked me too, especially because Jack was bringing me around. I enjoyed their stories and their expressions and earthy humor. It was always a refreshing change from the hubbub of city life and the complexities of college.

In the late fall of the following year, Jack surprised me and Mommy by showing us what he had been doing during his spare time: he had been restoring the old shack. Now it truly looked like the toothpick-legged Cajun home in my fantasy. The new tin roof gleamed in the sunlight. He had replaced and stained the railings on the gallery and the steps, removed the broken floorboards, replaced the windows, and cleaned up and trimmed the grounds. He had even restored the racks where Mommy and Great-Grandmère Catherine used to sell their handicrafts and gumbo to the tourists.

Mommy beamed. She clapped her hands with joy and amazement and went through the shack declaring her astonishment and pleasure. Jack had repaired the old rocker, too. Mommy said she could stand back and easily imagine her grandmère sitting in it again. While she relaxed on the galerie and reminisced, Jack and I walked to the water. He held my hand.

"See that current there?" He pointed. "Watch. In a minute you're going to see a big snapper. There she is. See her?"

"I do, Jack. Yes."

I took a deep breath and looked down the canal to where it turned into the deeper swamps. Jack saw the direction my eyes had taken.

"You can get to Cypress Woods from here in a pirogue," he said. "I'll take you for a ride next time."

"My uncle Paul used to take my mother that way," I said. "She told me so. You think there's some power that makes us want to retrace the steps our parents took?"

"Power? I don't know. Maybe. I don't worry about it. I do what feels right, feels good," he said. "Is that too simple for you?"

"No." I laughed. "You still think I'm too brainy, don't you?"

"Well . . . you're getting better," he teased. "And growing more beautiful with every passing day."

I looked at him for a moment and then we kissed. On the front gallery, Mommy was sitting in Great-Grandmère Catherine's restored rocker, drifting back through time and reliving her youth. I was sure she heard and saw again the people she had loved.

And I realized how important it was not to lose the precious moment when it came.

"For a while, Jack Clovis, you had me wondering where I belonged."

"Oh. Where do you belong?" he asked, his dark eyes searching mine.

"In your arms."

"Even here?"

"Especially here," I said. He put his arm around me. A flock of rice birds rose from the marsh and flew past us, so close we could feel the breeze from their flapping wings. It was just the way it had always been in my old nightmare.

Only now the demons were gone.

And I was truly safe.

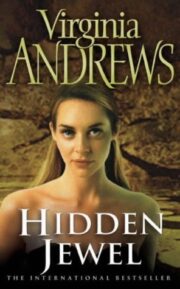

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.