So many people attended Jean's funeral that the crowd of mourners spilled out of the church door and down the steps onto the sidewalk. A few of my school friends were there, but I didn't see Claude. I knew Catherine had gone on a holiday with her family and wouldn't find out about Jean until she returned. Mommy, somewhat sedated, moved in a dreamlike state, her face sculptured in a tight grimace that sometimes appeared like an angelic smile but told me of the deep pain she was feeling from her toes to her head and into the very essence of her soul. By now everyone knew how Pierre's condition compounded our tragedy. He was still hooked to an I.V., still catatonic.

After the church service, the procession wound its way to the cemetery. I recalled Jean's and Pierre's questions about the vaults—what we in New Orleans call the burial ovens—built above ground because of the water table. What had once been a place of intrigue and curiosity to Jean would now serve as his home and resting place.

Daddy and Mommy clung tightly to each other. Most of the time, Daddy was holding Mommy up, her legs moving like the legs of a marionette on a string. I remained as close to her as I could, ready to embrace her myself if she started to topple. At the gravesite, the three of us embraced. I don't think any of us actually heard the priest's words. There was just the morbid rhythm of his voice reciting the prayers. He showered the holy water on Jean's casket and finally said "Amen."

I barely had raised my eyes higher than Mommy's and Daddy's faces all day, so I wasn't aware of the blue sky. To me it was a totally overcast day with only a slight breeze.

As we turned to walk back to our limousine, I saw Sophie standing under a tree. She was grinding the tears out of her eyes with her small fist, but the sight of her gave me a boost and helped me manage the journey home.

Mommy went right to bed. Daddy sat on the sofa in the sitting room greeting people and sipping from a tumbler of bourbon. As soon as I had the opportunity, I called the hospital, hoping Pierre had begun his recovery. We so desperately needed a morsel of good news, but his condition remained unchanged.

I decided I had to go to him, that a full day without any of us at his side was unacceptable, even though it was Jean's funeral day. I whispered my intentions to Daddy, who just nodded. He was numb with grief and unaware of what was happening around him.

At the hospital I met Dr. LeFevre in the hallway. She had just been in to see Pierre. "I'm going to move Pierre to the psychiatric unit," she said. "His recovery is going to take longer than I first anticipated. The emotional wound goes deep. I gather he and Jean were very close."

"Inseparable," I said, "and very protective of each other."

"Well, I know it's a difficult time for you and your parents, but try to give him as much time as you can. Just hearing your voice, feeling you beside him, will help reassure him and make his recovery that much more likely," she added. I didn't like the way her eyes shifted away from me.

"Do you think he will recover? I mean, will he be all right?"

"We'll see," she said in a noncommittal tone and walked off.

I put my chair as close to Pierre's bed as I could and sat holding his free hand. He stared ahead, blinking, his lips slightly open. I stroked his hand and spoke softly to him.

"You've got to try to get better, Pierre. Mommy and Daddy desperately need you to get better. I need you. Jean wouldn't want you to be like this. He would want you to help Mommy and Daddy. Please try, Pierre."

I sat there, waiting, watching. Except for the reflexive movement of his eyelids, he was like a statue made of human skin and bones. His ears and his eyes had brought him shocking, horrible information, and he had shut them down as a result, locking out any further details. Somewhere inside himself he was safe; he was playing with Jean; he could hear Jean's voice and see him. He didn't want to hear my voice, for my voice would shatter the illusion like thin china, and the shards would stab him in his heart forever and ever.

Sophie stopped in before going on duty, and I thanked her for coming to the funeral. She promised she would peek in on Pierre whenever she could and talk to him, too. I told her he would soon be moved to the psychiatric wing.

"That's all right. I'll get up there, too," she promised. We hugged, and she went to work. I remained as long as I could, talking to Pierre, pleading, soothing, cajoling him to return to us. Finally, exhausted myself, I went home.

All of the mourners had gone. The house was dead silent. Aubrey told me Daddy had retreated to his study. I found him sprawled on his leather sofa, mercifully asleep. I put a blanket over him and then went up to see Mommy.

At first I thought she was asleep too, but she turned her head slowly toward me and opened her eyes like someone who had risen from the grave. She reached out for me, and I hurried to her side and took her hand. We embraced, and then I sat beside her.

"Where's your father?" she asked.

"In his study, asleep."

"Did you go to see Pierre?"

I nodded. "The doctor wants to move him to the psychiatric ward so he can get the kind of treatment he needs," I told her.

"Then he's no better?"

"Not yet, Mommy. But he will be."

She shook her head and looked away. "Don't think your sins ever go away," she said. "You confess, you perform penance, you hope for forgiveness, but your sins are indelible. They hover like parasites, waiting for an opportunity to feed on your good fortune."

"You've got to stop doing this to yourself, Mommy."

"Listen to me, Pearl," she said tightening her grip on my hand. "You're brighter than I was at your age. You won't make the same mistakes, and you won't succumb to your weaknesses. You don't have the weaknesses I had. And that is good because you don't just hurt yourself, you hurt those you love and who love you."

"Mommy?"

"No. What could a free, innocent soul like Jean possibly have done to be so punished? This is not his doing. The weight of my sins was placed on him, and he suffered because of that, don't you see?

"Nina knew," she muttered. "Nina knew."

I sighed so deeply and loudly that she spun on me.

"A long time ago I did a bad thing, and I'm not referring to getting pregnant with you. You are too beautiful, too wonderful, to be anything but good; but after you were born, we were alone in the bayou."

"You told me this, Mommy. You don't have to explain."

"I want to explain. I need to explain. I didn't agree to marry your uncle Paul just because your father was off in Europe living the rich young man's life."

"But you thought he had become engaged and there was no hope of you two ever marrying," I reminded her.

"Yes, yes, but Paul was my half brother. True, we didn't learn that truth until we were both teenagers and after Paul had already fallen in love with me, but that didn't excuse it."

"Excuse what, Mommy? Look how we were living when you returned to the bayou. Why shouldn't you have agreed to live at Cyprus Woods? You said everyone thought I was his child anyway."

"Yes, they did, and he did little to convince them otherwise."

"Why are you telling me all this again?"

"Because I gave in to him and let him talk me into marrying him. We actually were married by a priest."

"But you told me that was just a marriage of convenience, that you and Paul were like roommates."

"Not always," she said. "There was a time when we pretended we were other people, people from the past, and . . . I sinned.

"I didn't do penance; I didn't ask forgiveness. I pretended it didn't happen, but the sin was part of my shadow and followed me from the bayou. Slowly that shadow moved over this house and this family until it claimed my poor Jean."

"Oh, Mommy, no," I said. I shook my head. It hurt me to learn this, but I couldn't believe God would punish Jean for Mommy's sin.

She closed her eyes. "I'm so tired, but I don't sleep. I see only Jean's face, see only Beau rushing from the swamp with him in his arms. And when I looked back, I saw that shadow smiling triumphantly at me."

She opened her eyes and seized my hand. "Jean is still here, still with us, still in this house. I want you to go back to Nina's house and see her sister. I want you to tell her what's happened and get her to bring the right charms here."

"Mommy, you're talking nonsense. Daddy wouldn't let us bring charms into this house anyway."

"You've got to do it, Pearl," she said, her eyes wide. "Will you promise?" she demanded. I saw she wouldn't rest until she had my word.

"Okay, Mommy. I promise."

"Good. Good," she said, releasing my hand and closing her eyes again. "Now I can sleep."

I sat there for a while staring at her until her breathing became slow and regular. Then I got up quietly and slipped from her room, thinking about the heavy burden of guilt Mommy had kept buried in the vault of her memory. Surely it had weighed down her heart before, but she had been able to pretend it had never happened. She had been lonely and afraid, I told myself. Everyone she loved but Paul had deserted her. I could never blame her for anything evil. Never.

Mommy was like an invalid for the next few days, never leaving her room, getting up only to bathe and change her nightgown. Daddy and I visited Pierre often in the psychiatric ward. Daddy did a little work, but by early evening, he was usually in his study drinking bourbon to help him sleep.

One afternoon about four days later, I went to the hospital first. I started talking to Pierre the same way I always did: first reviewing the things that had happened at the house, the people who called, the friends of Pierre's and Jean's who had asked about him. I talked and talked and stroked his hand and kissed his cheek and told him how much Mommy needed him. And then the nurse's aide brought in some juice and as usual, I tried to get Pierre to take something by mouth.

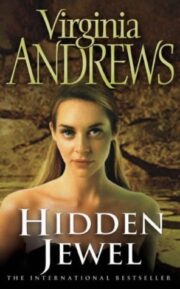

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.