"They are perfect, William," she had replied, "and Pierre Blanc himself could have done no better." For she must play the boy again, for the last time, and escape from her woman's clothes for this night at least. "I will be able to run better without petticoats," she said to William, "and I can ride astride my horse, as I used to as a child." He had procured the horses, as he had promised, and was to meet her with them on the road from Navron to Gweek just after nine o'clock.

"You must not forget, my William," she said, "that you are a physician, and that I am your groom, and it were better that you should drop 'my lady' and call me Tom."

He looked away from her in embarrassment. "My lady," he said, "my lips could not frame the word, it would be too distressing." She had laughed, and told him that physicians must never be embarrassed, especially when they had just brought sons and heirs into the world. And now she was dressing herself in the lad's clothes, and they fitted her well, even the shoes, unlike the clumsy clogs belonging to Pierre Blanc; there was a handkerchief too, which she wound about her head, and a leather strap for her waist. She looked at herself in the mirror, her dark curls concealed, her skin a gypsy brown, and "I am a cabin-boy again," she thought, "and Dona St. Columb is asleep and dreaming."

She listened at her door, and all was still; the servants were safe in their own quarters. She braced herself for the ordeal of descending the stairway to the dining-hall, for this was what she dreaded most, in the darkness, with the candles unlit, and flooding her mind with sharp intensity was the memory of Rockingham crouching there, his knife in his hands. It was better, she thought, to shut her eyes, and feel her way along the landing to the stairs, for then she would not see the great shield on the wall, nor the outline of the stairs themselves. So she went down, her hands before her and her eyes tight shut, and all the while her heart was beating, and it seemed to her that Rockingham still waited for her in the darkest corner of the hall. With a sudden panic she flung herself upon the door, wrenching back the bolts, and ran out into the gathering dusk to the safety and stillness of the avenue. Once she was free of the house she was no longer afraid, the air was soft and warm, and the gravel crunched under her feet, while high in the pale sky the new moon gleamed like a sickle.

She walked swiftly, for there was freedom in her boy's clothes, and her spirits rose, and once again she fell to whistling Pierre Blanc's song, and she thought of him too, with his merry monkey face and his white teeth, waiting now on the deck of La Mouette somewhere in mid-channel, for the master he had left behind.

She saw a shadow move towards her, round the bend of the road, and there was William with the horses, and there was a lad with him, Grace's brother she presumed, and the owner of the clothes she wore.

William left the boy with the horses, and came towards her, and she saw, the laughter rising within her, that he had borrowed a black suit of clothes, and white stockings, and he wore a dark curled wig.

"Was it a son or a daughter, Doctor Williams?" she asked, and he looked at her with confusion, not entirely happy at the part he had to play: for that he should be the gentleman and she the groom seemed to him shocking, who was shocked at nothing else.

"How much does he know?" she whispered, pointing to the lad.

"Nothing, my lady," he whispered, "only that I am a friend of Grace's, and am in hiding, and that you are a companion who would help me to escape."

"Then Tom I will be," she insisted, "and Tom I will remain." And she went on whistling Pierre Blanc's song, to discomfort William, and going to one of the horses she swung herself up into the saddle, and smiled at the lad, and digging her heels into the side of the horse, she clattered ahead of them along the road, laughing at them over her shoulder. When they came to the wall of Godolphin's estate they dismounted, and left the lad there with the horses, under cover of the trees. She and William went on foot the half-mile to the park-gates, for so they had arranged earlier in the evening.

It was dark now, with the first stars in the sky, and they said nothing to one another as they walked, for all had been planned and put in readiness. They felt like actors who must appear upon the boards for the first time, with an audience who might be hostile. The gates were shut, and they turned aside, and climbed the wall into the park, and crept towards the drive under shadow of the trees. In the distance they could see the outline of the house, and there was a light still in the line of windows above the door.

"The son and heir still tarries," whispered Dona. She went on ahead of William to the house, and there, at the entrance to the stables, she could see the physician's carriage drawn up on the cobbled stones, and the coachman was seated with one of Godolphin's grooms on an upturned seat beneath a lantern, thumbing a pack of cards. She could hear the low murmur of the voices, and their laughter. She turned back again, and went to William. He was standing beside the drive, his small white face dwarfed by his borrowed wig and his hat. She could see the butt of his pistol beneath his coat, and his mouth was set in a firm thin line.

"Are you ready?" she said, and he nodded, his eyes fixed upon her, and he followed her along the drive to the keep. She had a moment of misgiving, for she realised suddenly that perhaps, like other actors, he lacked confidence in his part, and would stumble over his words, and the game would be lost because William, upon whom so much depended, had no skill. As they stood before the closed door of the keep she looked at him, and tapped him on the shoulder, and for the first time that evening he smiled, his small eyes twinkling in his round face, and her faith in him returned, for he would not fail.

He had become, in a moment, the physician, and as he knocked upon the door of the keep, he called, in full round tones surprisingly unlike the William she knew at Navron: "Is there one Zachariah Smith within, and may Doctor Williams from Helston have a word with him?"

Dona could hear an answering shout from the keep, and in a moment the door swung open, and there was her friend the guard standing on the threshold, his jacket thrown aside because of the heat, his sleeves rolled high above his elbows, and a grin on his face from ear to ear.

"So her ladyship didn't forget her promise?" he said. "Well, come inside, sir, you are very welcome, and we have enough ale here, I tell you, to christen the baby and yourself into the bargain. was it a boy?"

"It was indeed, my friend," said William, a fine boy, and the image of his lordship." He rubbed his hands together, as though in satisfaction, and followed the jailer within, while the door was left ajar, so that Dona, crouching beside the wall of the keep, could hear them move about the entrance, and she could hear too the clink of glasses, and the laughter of the guard. "Well, sir," he was saying, "I've fathered fourteen and I may say I know the business as well as you. What was the weight of the child?"

"Ah," said William, "the weight now… let me see," and Dona, choking back her laughter, could picture him standing there, his brows drawn together in perplexity, ignorant as a baby himself would be at such a question. "Round about four pounds I should say, though I cannot recollect the exact figure…" he began, and there came a whistle of astonishment from the jailer, and a burst of laughter from his assistant.

"Do you call that a fine boy?" he said, "why, curse me, sir, the child will never live. My youngest turned the scale at eleven pounds when he was born, and he looked a shrimp at that."

"Did I say four?" broke in William hastily, "a mistake of course. I meant fourteen. Nay, now I come to remember, it was somewhere around fifteen or sixteen pounds."

The jailer whistled again.

"God save you, sir, but that's something over the odds. It's her ladyship you must look to, and not the child. Is she well?"

"Very well," said William, "and in excellent spirits. When I left her she was discussing with his lordship what names she would bestow upon her son."

"Then she's a pluckier woman than I'd ever give her credit for," answered the jailer. "Well, sir, it seems to me you deserve three glasses after that. To bring a child of sixteen pounds into the world is a hard evening's work. Here's luck, sir, to you, and the child, and to the lady who drank with us here this evening, for she's worth twenty Lady Godolphins if I'm not mistaken."

There was silence a moment, and the clinking of glasses, and Dona heard a great sigh from the jailer, and a smacking of lips.

"I warrant they don't brew stuff like that in France," he said, "it's all grapes and frogs over there, isn't it, and snails, and such-like? I took a glass just now to my prisoner above, and you'll scarcely credit me, sir, but he's a cool-blooded fish for a dying man, as you might say. He quaffed his ale in one draught and he slapped me on the shoulder, laughing."

"It's the foreign blood," broke in the second guard. "They're all alike, Frenchmen, Dutchmen, Spaniards, no matter what they are. Women and drink is all they think about, and when you're not looking it's a stab in the back."

"And what does he do his last day," continued Zachariah, "but cover sheets of paper with birds, and sit there smoking and smiling to himself. You'd think he'd send for a priest, for they're all papists, these fellows; it's robbery and rape one minute and confession and crucifixes the next. But not our Frenchman. He's a law to himself, I reckon. Will you have another glass, doctor?"

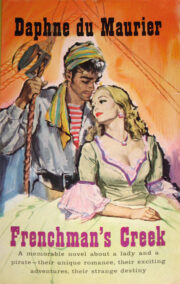

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.