He poured the ale into the glasses, and Dona, clinking hers against the jailer's said, "Long life, then, to the future Lord Godolphin."

The jailer smacked his lips, and tilted his head.

The prisoner raised his glass and smiled at Dona.

"Should we not also drink to Lady Godolphin, at this moment, I imagine, suffering something of discomfort?"

"And," replied Dona, "to the physician also, who will be rather heated." As she drank, an idea flashed suddenly to her mind, and glancing at the Frenchman, she knew instinctively that the same thought had come to him, for he was looking at her.

"Zachariah Smith, are you a married man?" she said.

The jailer laughed. "Twice married," he said, "and the father of fourteen."

"Then you know what his lordship is enduring at this moment," she smiled, "but with so able a physician as Doctor Williams there is little cause for anxiety. You know the doctor well, I suppose?"

"No, my lady. I come from the north coast. I am not a Helston man."

"Doctor Williams," said Dona dreamily, "is a funny little fellow, with a round solemn face, and a mouth like a button. I have heard it said that he is as good a judge of ale as any man living."

"Then it's a great pity," said the prisoner, laying down his glass, "that he does not drink with us now. Perhaps he will do so later, when his day's work is finished, and he has made a father of Lord Godolphin."

"Which will not be much before midnight, what do you say, Zachariah Smith, and father of fourteen?" asked Dona.

"Midnight is generally the hour, your ladyship," laughed the jailer, "all nine of my boys were born as the clock struck twelve."

"Very well, then," said Dona, "when I see Doctor Williams directly I will tell him that in honour of the occasion, Zachariah Smith, who can boast of more than a baker's dozen, will be pleased to drink a glass of ale with him before he goes on duty for the night."

"Zachariah, you will remember this evening for the rest of your life," said the prisoner.

The jailer replaced the glasses on the tray. "If Lord Godolphin has a son," he said, winking an eye, "there'll be so much rejoicing on the estate that we'll be forgetting to hang you in the morning."

Dona took up the drawing of the sea-gull from the table.

"Well," she said, "I have chosen my drawing. And rather than his lordship should see you with the tray, Zachariah, I will descend with you, and we will leave your prisoner with his pen and his birds. Good-bye, Frenchman, and may you slip away to-morrow as easily as the feather did from my mattress."

The prisoner bowed. "It will all depend," he said, "upon the quantity of ale that my jailer consumes to-night with Doctor Williams."

"He'll have to boast a stout head if he can beat mine," said the jailer, and he unlocked the door, and held it open for her to pass.

"Good-bye, Lady St. Columb," said the prisoner, and she stood for a moment looking at him, realising that the plan they had in mind was more hazardous and more foolhardy than any that he had yet attempted, and that if it should fail there would be no further chance of escape, for tomorrow he would hang from the tree there in the park. Then he smiled, as though in secret, and it seemed to her that his smile was the personification of himself; it was the thing in him that she had first loved, and would always cherish, and it conjured the picture in her mind of La Mouette, and the sun, and the wind upon the sea, and with it too the dark shadows of the creek, the wood fire and the silence. She went out of the cell without looking at him, her head in the air, and her drawing in her hand, and "He will never know," she thought, "at what moment I have loved him best."

She followed the jailer down the narrow stair, her heart heavy, her body suddenly tired with all the weariness of anti-climax. The jailer, grinning at her, put the tray under the steps, and said, "Cold-blooded, isn't he, for a man about to die? They say these Frenchmen have no feelings."

She summoned a smile, and held out her hand. "You are a good fellow, Zachariah," she said, "and may you drink many glasses of ale in the future, and some of them to-night. I won't forget to tell the physician to call upon you. A little man, remember, with a mouth like a button."

"But a throat like a well," laughed the jailer. "Very good, your ladyship, I will look out for him, and he shall quench his thirst. Not a word to his lordship, though."

"Not a word, Zachariah," said Dona solemnly, and she went out of the dark keep into the sunshine, and there was Godolphin himself coming down the drive to meet her.

"You were wrong, madam," he said, wiping his forehead, "the carriage has not moved, and the physician is still with my wife. He has decided after all that he will remain for the present, as poor Lucy is in some distress. Your ears must have played you false."

"And I sent you back to the house, all to no purpose," said Dona. "So very stupid of me, dear Lord Godolphin, but then women, you know, are very stupid creatures. Here is the picture of a sea-gull. Do you think it will please His Majesty?"

"You are a better judge of his taste than I, madam," said Godolphin, "or so I presume. Well, did you find the pirate as ruthless as you expected?"

"Prison has softened him, my lord, or perhaps it is not prison, but the realisation that in your keeping, escape is impossible. It seemed to me that when he looked at you he knew that he had at last met a better, and a more cunning brain than his own."

"Ah, he gave you that impression, did he? Strange, I have sometimes thought the opposite. But these foreigners are half women, you know. You never know what they are thinking."

"Very true, my lord." They stood before the steps of the house, and there was the physician's carriage, and the servant still holding Dona's cob. "You will take some refreshment, madam, before you go?" enquired Godolphin, and "No," she answered, "no, I have stayed too long as it is, for I have much to do to-night before my journey in the morning. My respects to your wife, when she is in a state to receive them, and I hope that before the evening is out, she will have presented you with a replica of yourself, dear Lord Godolphin."

"That, madam," he said gravely, "is in the hands of the Almighty."

"But very soon," she said, mounting her horse, "in the equally capable hands of the physician. Good-bye." She waved her hand to him, and was gone, striking the cob into a startled canter with her whip, and as she drew rein past the keep and looked up at the slit in the tower she whistled a bar of the song that Pierre Blanc played on his lute, and slowly, like a snow-flake, a feather drifted down in the air towards her, a feather torn from the quill of a pen. She caught it, caring not a whit if Godolphin saw her from the steps of his house, and she waved her hand again, and rode out onto the highroad laughing, with the feather in her hat.

Chapter XXIII

DONA LEANED from the casement of her bedroom at Navron, and as she looked up into the sky she saw, for the first time, the little gold crescent of the new moon high above the dark trees.

"That is for luck," she thought, and she waited a moment, watching the shadows in the still garden, and breathing the heavy sweet scent of the magnolia tree that climbed the wall beneath her. These things must be stored and remembered in her heart with all the other beauty that had gone, for she would never look upon them again.

Already the room itself wore the appearance of desertion, like the rest of the house, and her boxes were strapped upon the floor, her clothes folded and packed by the maid-servant, according to instruction. When she had returned, late in the afternoon, hot and dusty from her ride, and the groom had taken the cob from her in the courtyard, the ostler from the Inn at Helston was waiting to speak to her.

"Sir Harry left word with us, your ladyship," he said, "that you would be hiring a chaise to-morrow, to follow him to Okehampton."

"Yes," she said.

"And the landlord sent me to tell you, your ladyship, that the chaise will be available, and will be here for you at noon to-morrow."

"Thank you," she had said, staring away from him towards the trees in the avenue, and the woods that led to the creek, for everything he said to her lacked reality, the future was something with which she had no concern. As she left him and went into the house he looked after her, puzzled, scratching his head, for she seemed to him like a sleepwalker, and he did not believe she had fully understood what he had told her. She wandered then to the nursery, and stared down at the stripped beds, and the bare boards, for the carpets had been taken up. The curtains were drawn too, and the air was already hot and unused. Beneath one of the beds lay the arm of a stuffed rabbit that James had sucked, and then torn from the rabbit's body in a tantrum.

She picked it up and held it, turning it over in her hands. There was something forlorn about it, like a relic of by-gone days. She could not leave it lying there on the floor, so she opened the great wardrobe in the corner, and threw it inside, and shut the door upon it, then left the room and did not go into it again.

At seven her supper was brought to her on a tray, and she ate little of it, not being hungry. Then she gave orders to the servant not to disturb her again during the evening, for she was tired, and not to call her in the morning, for she would sleep late in all probability, before the tedium of the journey.

When she was alone, she undid the bundle that William had given her on her return from Lord Godolphin. Smiling to herself she drew out the rough stockings, the worn breeches, and the patched though gaily coloured shirt. She remembered his look of embarrassment as he had given them to her, and his words: "These are the best Grace can do for you, my lady, they belong to her brother."

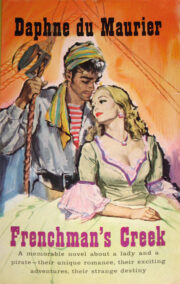

"Frenchman’s Creek" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Frenchman’s Creek". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Frenchman’s Creek" друзьям в соцсетях.