‘He has gone for a year, not for ever,’ I said.

‘I only hope it may be so,’ she said, relishing the new situation and determined to make a drama of it. ‘But who knows what may happen to a man, once he leaves his own fireside? There are villains everywhere. At this very minute, Sir Thomas may be in the power of pirates.’

‘Sir Thomas will not have been caught by pirates, will he?’ asked Mama, stirring.

‘I hardly think so,’ I told her.

‘Who can say?’ countered Aunt Norris. ‘The sea is a very unsafe place. And if he has not been captured by pirates, then what other dangers might he not be facing? There are typhoons and tidal waves... I shall not be surprised if Sir Thomas is shipwrecked, only to return to us after fifteen years with long white hair and a beard.’

Mama was alarmed.

‘Do not say so! I have never been able to abide a beard,’ she said.

‘Depend upon it, he will have fine weather and make the crossing in a month,’ I told her.

‘If he is not set upon by an enemy vessel,’ said my aunt, ‘for then he will be thrown into the sea, as like as not, and eaten by a whale.’

Fanny heroically distracted my aunt’s attention, allowing us to pass the rest of the evening without any further visions fit for one of Mrs. Radcliffe’s novels.

DECEMBER

Wednesday 31 December

The last day of the year, and nothing terrible has happened. Papa has not been shipwrecked, nor has he drowned in a storm, nor been eaten by a whale. And I have managed to maintain the estate and family without them suffering any calamities either, for which I am truly thankful. I was able to write to Papa today and tell him that the estate is flourishing; that Maria and Julia are fast becoming the belles of the neighborhood; and that Fanny’s strength is improving by virtue of her daily rides. I gave him news of Mama and Aunt Norris, and sent him my best wishes for his affairs in Antigua.

I have survived the year, and I only hope I can survive the next one, so that I can hand both estate and family back to my father and turn my attention to my own life again.

1807

MAY

Wednesday 27 May

I am beset with problems on every side. Having just returned from my dealings with the bank in London I found that Fanny’s grey pony had died, and that neither Mama nor Aunt Norris had thought of buying her another one. I said at once that I meant to rectify the situation, only to find myself blocked at every turn.

‘There is no need to buy a pony just for Fanny. I am sure she does not expect it,’ said my aunt, as though that justified the omission.

Mama said she might borrow Maria’s horse, or Julia’s, but on enquiring, I found out that my sisters’ horses were never free in fine weather, and of what use would it be for Fanny to ride in the rain?

‘That is true,’ said Mama.

‘But there is no need to buy something especially,’ said my aunt. ‘There must be an old thing among the horses belonging to the Park that would do. Why, I am sure Fanny could borrow one from the steward whenever she wanted one. That would be a much better solution.’

‘No young lady of Mansfield Park will ride a steward’s horse,’ I told her. She switched to another tack, saying my father would not want her to have one.

‘Indeed, it would be improper for Fanny, situated as she is, to have a young lady’s horse, quite as though she were a daughter of the house,’ said my aunt. ‘The distinctions of rank must be preserved. Sir Thomas himself said so. It would not do to let Fanny get above herself.’

‘Fanny is the last person in the world who would ever get above herself. Besides, she must have a horse. Do you not agree?’ I appealed to Mama.

‘Oh, yes, to be sure, she must have a horse. As soon as Sir Thomas comes home she must have one. Only leave it to him, Edmund. Your father will know what to do, and it is not so very long until September, when he returns.’

‘It is four months, and Fanny cannot go without her exercise for so long, particularly in the summer months.’

‘Your father would not agree with the idea, I am sure,’ said my aunt, shaking her head, ‘and to be making such a purchase, with his money, in his absence, when his affairs are unsettled seems to me to be a very wrong thing. It is not only the expense of the purchase, but the expense of keeping the animal.’

Against my will, I found myself agreeing with her. My father’s last letter spoke of ever dwindling profits, and I could tell how worried he was.

I was at a stand, and I walked over to the window, displeased. I was determined to secure to Fanny the pleasure of regular outings, but I could not see how to do it, until, glancing across the park, I saw my own horses being given their exercise. I immediately saw a way round the problem.

‘I must give Fanny one of my horses,’ I said.

‘There is no need for you to inconvenience yourself, that would be quite wrong. You, a Bertram, and a son of the house, to give up one of your horses? I am sure Fanny would be the first to protest against it. Besides, your horses are not fit for a woman to ride. Two of them are hunters and the third is a road horse. They are all of them far too strong and spirited. Fanny would fall and break her neck, most likely,’ said Aunt Norris.

Knowing she was right, I decided to exchange one of my horses for an animal that Fanny can ride. I know where one is to be met with, and I mean to look it over tomorrow.

JUNE

Monday 8 June

I have been rewarded for my small trouble by seeing Fanny so happy. The new mare suits her very well.

‘I never thought anything could replace the old grey pony in my affections, but my delight in the mare is so far beyond my former pleasure... It is so good of you... I cannot express my gratitude.’

‘There is no need for gratitude between friends,’ I said, smiling. ‘It is enough for me to see you happy and well. shall we ride to the stone cross? Then we can discuss Shakespeare on the way. I have barely seen you since I returned from London, and I have had no one to discuss poetry with whilst I was away.’

The summer afternoon was such as to encourage our taste for poetry and we returned in a happy mood, to while away the evening in the same manner.

SEPTEMBER

Saturday 12 September

It is a good thing I did not wait for my father to come home before providing Fanny with a horse, for I had a letter from him this morning saying that his affairs are still in such a state that he cannot come home until next year. I was not as alarmed by this as I would have been a few months ago, for I have learnt how to manage the estate and I believe it to be prospering.

Friday 25 September

We have all been thrown into an uproar, for Tom is home! He arrived late this afternoon, as careless and laughing as ever, but as brown as a nut, and with hair so bleached by the sun it resembled a piece of driftwood. He was barely recognizable, being slimmer and fitter than when he went away, with his eyes looking so green in the brown of his face that my aunt was moved to say that they looked like a pair of emeralds.

‘All the better for wooing,’ said Tom merrily, catching her round the waist and spinning her round before putting her down, breathless.

Mama bestirred herself so far as to leave the sofa and kiss him, and he repaid her with a kiss on the cheek. He delighted her by asking after Pug, who sat like a fat potentate on the sofa, and then turned his attention to Maria and Julia. They were pleased to see him, and eager to discover what was in the packages that had followed him into the room. He had brought presents for us all: exotic material for Mama and my aunt — ‘To make you some splendid new gowns. You will be the talk of the neighborhood’ — fans and shoes for Maria and Julia, a pair of shoes for Fanny and a compass for me.

‘How is Sir Thomas?’ asked Mama, when she had seated herself once more on the sofa with Pug on her lap.

‘Very well.’

‘It is a terrible thing for him to be so far from home. I wished he would not go, but he said he must, and there was an end of it. I do not like to think of him in all that heat, on his own. He will miss us all dreadfully.’

‘He scarcely has time. There is plenty to do, and he is busy from morning ’til night.’

‘How are his affairs?’ I asked.

‘Lord knows. I could not make head nor tail of them. Sugar plantations are a mystery to me. Now horses...’

‘You have not been gambling again, Tom?’ asked Aunt Norris.

‘No. I have promised my father not to bet on another card or horse — at least until his affairs are settled!’ he added.

‘Impudent boy!’ said Aunt Norris indulgently. ‘But, were it not for the joy you bring us by returning like this, I cannot help thinking that it must bode ill for Sir Thomas,’ she went on, shaking her head. ‘Indeed, it is a singularly bad portent. It is so like Sir Thomas to send you home if he had a foreboding of evil. I have a terrible presentiment that something dreadful is about to occur.’

Mama was beginning to look worried, and stir anxiously on the sofa, so Fanny put an end to my aunt’s woeful imaginings by saying to Tom, ‘Tell us about Antigua.’

Tom was only too happy to talk, for he was full of energy and liveliness.

‘It was hot,’ he began. ‘Very hot. You would not believe the heat, little Fanny. Not all your hats and fans and parasols would keep you cool. I believe the ladies there were made from less pliable material than those at home, for they bore it well, and managed to walk around with only a little droop, instead of melting like candles.’

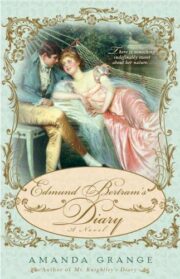

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.