I felt sick. To hear Mary speak of my ordination as a foolish precipitation, a stain that could be hidden with varnish and gilding, instead of seeing it as my calling, an inalienable part of me, and one that needed no excusing was abhorrent to me. And what was this varnish and gilding to be?

A baronetcy. A baronetcy I was to gain by the death of my brother; by the death of Tom. Tom, who had been a part of my life always; Tom, who had ridden beside me, wrestled with me, swum with me; Tom who had laughed at me, plagued me and teased me. And Mary wished him dead.

Not only that, but she said Fanny wished it, too; that Fanny was smiling and looking cunning at the idea of it. Fanny, who could not look cunning if she tried; Fanny, who would be incapable of wishing evil on anyone; Fanny, who loved my brother for all the kindnesses he had shown her. I handed Fanny back the letter, feeling as though all life had been sucked out of me.

‘If not for you, Fanny, I do not know how I would bear it. And yet you, yourself, are suffering. Crawford played you false.’

‘No, I am not suffering,’ she said softly, folding the letter and letting it rest on her lap, where her goodness seemed to undo its malice, rendering it harmless.

I looked at her in confusion, wondering what she meant, for it must hurt her to know that her lover had betrayed her.

‘I never loved him, and I never wanted him to love me,’ she said. ‘Indeed, I do not believe he did. I saw his behavior towards Maria last year, and I suspected there was still an attachment between them. That is why I could not marry him. That, and—’

She stopped, and I did not press her. I knew her heart was too full to speak.

‘But is this true, Fanny? Is this really true?’ I asked her. ‘Has he not hurt you?’

‘No.’

‘Then it takes a great weight from my mind,’ I said in relief, feeling that here, at last, was something to smile about, some cheer to brighten the gloom. ‘You saw more than I did, Fanny. I was blinded in more than one way at the time. It is a funny thing, I used to be the teacher and you my pupil, but it seems that our roles have been reversed.’

She gave me a look of understanding, and I thought: Fanny has grown up. My mother rousing herself at that moment, for she had been asleep in front of the fire, our conversation came to an end.

Monday 22 May

Fanny and I went riding this morning. We rode in silence to begin with, for I was thinking about Mary and how I had taught her to ride. I remembered her enjoyment, and her saying that she was growing to love the country. But although my feelings were, to begin with, wistful, they began to change as I watched Fanny, who was riding beside me. Her face showed pleasure in the exercise and her enjoyment in the countryside. Hers was not the bright-eyed pleasure of novelty, it was the deep-seated pleasure of long acquaintance and genuine love. Her eyes sought out the new buds springing to life and the changes taking place around her. She would ride thus in ten years, twenty years, time, as I would, never growing restless or dissatisfied, because she belonged at Mansfield Park. I was reminded of my ride with Tom when we were boys, and the way his eyes had always looked beyond Mansfield. Mary’s eyes had looked beyond Mansfield, too. But Fanny’s never did. At Mansfield, she was at home.

‘I am beginning to think it is a good thing we are alone again,’ I said. ‘I missed going for rides with you, Fanny, when Mary was here.’ She looked at me anxiously, and I said, ‘There is no need to worry. I can speak her name without pain. I was hurt, it is true, but the countryside, and friends, can heal anything in time. If I am not deceived, the sable cloud has turned forth her silver lining on the night.’

She smiled.

‘Milton would forgive you your deviation, glad that you have seen the truth of his words, as your friends must be,’ she said.

We passed Robert Pinker and bade him good morning. We had just passed him when he called out, ‘Mr. Bertram!’

We reined in our horses and he approached.

‘I wonder if I could call on you this afternoon, at Thornton Lacey?’ he said.

‘By all means. Was there something particular you wished to see me about?’

He went red and stammered that Miss Colton had been good enough to accept his offer of marriage.

‘This is splendid news,’ I said, and Fanny added her heartfelt good wishes.

‘We would like to be married at the end of June,’ he said. ‘I have a house, there is nothing to wait for.’

‘Then call on me at three o’clock and we will discuss it.’

He thanked me and we set off.

‘That will be a happy marriage,’ I said.

‘Yes, indeed,’ said Fanny. ‘I have been hoping for it for some time.’

‘You knew it was likely to take place?’

‘I visited Mrs. Colton when her mother was ill, and Mr. Pinker was there. Miss Colton looked at the floor and blushed a great deal.’

‘It is a puzzlement to me how women can behave so differently when they are in love. Mary was bold and confident — though perhaps she was not in love.’

‘I think she was, as much as she was capable of being,’ said Fanny.

‘Yes. Her nature perhaps admitted of no more. But Miss Colton was not bold, she blushed and looked at the floor. And yet when you did the same it meant quite the opposite, that you did not want Mr. Crawford’s attentions. I will never understand the fairer sex.’

‘Perhaps you will, in time,’ said Fanny, looking at me.

‘Perhaps.’

We turned for home.

‘I have had a letter from Julia,’ said my father, when we joined him and Mama in the drawing room. ‘She has begged my forgiveness and she now asks for the indulgence of my notice. I would like your advice, Edmund; and yours, too, Fanny. You have seen more clearly in this business than any of us.’

‘It seems to me to be a good sign,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ said Fanny. ‘If they wish to be forgiven, then I think you should notice them.’

She colored slightly for speaking so boldly but my father thanked her for her opinion.

‘What do you think, Lady Bertram?’ he asked.

‘I would like to see Julia again,’ she said wistfully, ‘and so would Pug.’

‘Then I will write and invite them to Mansfield Park. Perhaps something might be salvaged from the disasters that have befallen us over the last few weeks after all.’

‘Mr. Yates was frivolous but he was constant,’ said Fanny. ‘I believe he liked Julia from the first.’

‘Well, we shall see,’ said my father.

After luncheon, Fanny and I set out for Thornton Lacey, I to see Robert Pinker and Fanny to call on Mrs. Green, who has a new baby.

‘So that is the meaning of the dress you have been sewing,’ I said.

‘A new mother can never have too much linen,’ she replied.

We reached Thornton Lacey in good time and together we looked over the house.

‘Moving the farmyard has changed it completely,’ she said.

‘Yes, has it not?’

‘The approach is now one any gentleman might admire, and the prospect is much improved.’

‘And what do you think of the chimney piece?’

‘I think it is excellent,’ she said, running her hand across it. ‘It adds a great deal of beauty to the room. This is a good house, Edmund, and may be made more beautiful still if you wish.’

‘I am committed to improving it as much as I might.’

We went upstairs and she gave me the benefit of her advice on the cupboards before she left to see Mrs. Green. I soon received Robert Pinker, who told me of Miss Colton’s many virtues. I wished him happy and we arranged for the banns to be read. He left me in good spirits, and Fanny returned soon after, smiling brightly.

‘Mrs. Green was well?’

‘She was, and the baby was thriving.’

The world seemed a better place as we rode home together. Julia repentant, Tom improving, and Fanny growing in beauty and confidence daily.

I only hope it may continue.

Tuesday 30 May

Julia and Yates arrived this morning. There was some little awkwardness, but Julia was so humble and so wishing to be forgiven, and Yates was so much better than we had thought him, for he was truly desirous of being received into the family, that soon things became quite comfortable. My mother was delighted to have Julia restored to her, and the day ended more pleasantly than anyone could have rightfully expected.

JUNE

Thursday 1 June

‘This marriage of Julia’s is not so bad as I first feared,’ said my father to me this morning. ‘Yates is not very solid, but from a number of conversations I have had with him, I think there is every hope of him becoming less trifling as he grows older. His estate is more, and his debts less than I feared.’

Saturday 10 June

Our good news continues. Tom is now out of danger, and this morning he was able to take a short walk out of doors. The weather was fine, and the exercise did him good. I believe we will have him well again by the end of the summer, and none the worse for his fall.

Thursday 15 June

At last Maria and Crawford have been discovered. Maria refuses to leave Crawford, saying she is sure they will be married in time. Rushworth is determined to divorce her. It is a scandal, but we must endure it, for there is nothing else to be done.

Thursday 29 June

Fanny and I have grown into the habit of wandering outside in the evening, enjoying the balmy air, and sitting under trees talking of books and poetry. It is like the old days, before the Crawfords came to Mansfield Park, and yet with this change, that Fanny is no longer my protégée, she is my equal. She argues with me over the authors’ and poets’ intentions, and her arguments are well reasoned and compelling. She makes me rethink my position, and in so doing gives me a deeper understanding of the books and poems I so love. And when we have talked our fill, we watch the sun sinking over the meadows, and take as much pleasure from the sight of it as those in London society take in a necklace of rubies.

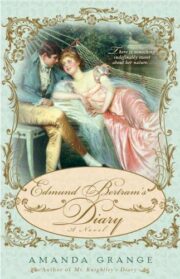

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.