‘I have often been aware of some differences in our opinions, but I never suspected something like this, that you would make light of your brother’s crime — for crime I call it to seduce a woman and take her away from her home — and all the time with no feelings for her. And to make light of wounding one of the gentlest creatures on earth. And then to suggest we promote a marriage that would lead to nothing but misery, for I would not ever want to see my sister married to such a man as your brother — the man I now know him to be. Inconstant, deceitful, immoral, everything that a man should not be. I see now that I have never understood you; that I have loved an image of you, and not you yourself.’

She did not know how to look. At first she was astonished, then she turned red, and I saw a mixture of many feelings, chief amongst them anger. I saw a great, though short struggle, half a wish of yielding to truths, half a sense of shame, but habit, habit carried it. She would have laughed if she could.

‘A pretty good lecture, upon my word. Was it part of your last sermon?’ she said sarcastically.

‘At this rate you will soon reform everybody at Mansfield and Thornton Lacey; and when I hear of you next, it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists, or as a missionary into foreign parts.’

But her words could no longer wound me. I only said in reply, that from my heart I wished her well, and earnestly hoped that she might soon learn to think more justly, and not owe the most valuable knowledge we could any of us acquire, the knowledge of ourselves, to the lessons of affliction. And then I left the room.

I had gone a few steps when I heard the door open behind me.

‘Mr. Bertram,’ said she. I looked back. ‘Mr. Bertram,’ said she, with a smile; but it was a smile ill suited to the conversation that had passed, a saucy playful smile, seeming to invite me in order to subdue me. I resisted; it was easy; and I walked on.

As I walked out of the house, I was shocked to see that our interview had lasted only twenty-five minutes. Such a short time to change so much!

I met my father soon afterwards, and though I did not tell him of everything that had passed he guessed it had not been good, for he suggested to me that I should write to Fanny and tell her to ready herself, then go to Portsmouth and take her home.

My gloom began to lift at the thought of seeing Fanny again, but I worried about leaving my father. He reassured me that he could manage alone, and so I sent my letter, telling Fanny I would be in Portsmouth tomorrow for the purpose of taking her back to Mansfield Park. I said also, at my father’s request, that she should invite her sister Susan for a few months, for he was sure Fanny would like to have some young person with her, someone who could help counteract her sorrow at the blow that had befallen her.

Wednesday 10 May

I arrived in Portsmouth early, by the mail, too worried to be tired by my lack of sleep, and by eight o’clock I was in Fanny’s house. I was shown into the parlor, and then Mrs. Price left me in order to attend to her household affairs whilst the servant called Fanny down. She came in, and I strode across the room, reaching her in two strides and taking her hands in mine, scarcely able to speak for happiness and relief at being with her again.

‘My Fanny — my only comfort now,’ I said, momentarily overcome. I collected myself, for what were my griefs compared to hers?

I asked if she had had breakfast, and when she would be ready. She told me that half an hour would do it, so I ordered the carriage and then took a walk round the ramparts. As I felt the stiff sea breeze, I thought of the moment I had taken Fanny’s hands, and I wondered at the strangeness of it, that her fingers were so tiny and yet they could put such strength into my own; for I had felt it flowing into me, strength and courage, when I had touched her, sustaining me in my misery, and I hoped that my touch had strengthened her, too. I was not long on the ramparts and was soon back at the house. The carriage arrived, and we were off.

I longed to talk to Fanny, but her sister’s presence kept me silent. The things I had to say were not for the ears of a fourteen-year-old girl. I tried to talk of indifferent subjects, but I could not make the effort for long, and soon fell into silence again.

And now we have stopped at an inn in Oxford for the night, but I am chafing at the delay. I want to get home, to Mansfield Park. I want to take Fanny to my mother.

Thursday 11 May

I had a chance to speak to Fanny a little this morning, for as we were standing by the fire waiting for the carriage, Susan went over to the window to watch a large family leaving the inn. Fanny looked so pale and drawn that I took her hand and said, ‘No wonder — you must feel it

— you must suffer. How a man who had once loved, could desert you!’ I could not believe Crawford could have been so vicious. But then my own pains rose up inside me, and I longed for the soothing comfort of Fanny’s voice, and the softness of her words. ‘But yours — your regard was new compared with — Fanny, think of me!’ I burst out. She found words for me, even in her own troubles, and then our journey began. I tried to set Susan at ease, and comfort Fanny, but my own anxieties were too much for me and after awhile, sunk in gloom, I closed my eyes, unable to bear the sight of burgeoning summer, which contrasted so heart-breakingly with the winter in my mind.

We reached Mansfield Park in good time, well before dinner, and my mother ran from the drawing-room to meet us. falling on Fanny’s neck, she said, ‘Dear Fanny! Now I shall be comfortable.’

And so it is. Fanny brings comfort with her wherever she goes. We went inside. My aunt, sitting in the drawing-room, did not look up. The recent events had stupefied her. I soon discovered that she felt it more than all of us, for she had always been very attached to Maria and Maria’s marriage had been of her making. For her to find it had ended in such a way had hit her very hard.

Tom was sitting on the sofa, looking less ill than previously, but still far from well. He had had a setback when he had learnt about Maria and Julia, but he had rallied and was gaining strength again.

Susan was remembered at last, and received by my mother with a kiss and quiet kindness. Susan, good soul, was so grown up for fourteen, and provided of such a store of her own happiness, that she took no notice of my aunt’s repulsive looks, for my aunt saw her as an intruder at such a time, and returned Mama’s greetings with sense and good cheer. We ate dinner in silence, and we were all of us glad, I think, to plead tiredness, and so go early to bed.

Friday 12 May

A letter has come from my father. He has not yet been able to find Maria, but he has reason to believe that Julia is now married. His letter was full of his feelings: that, under any circumstances it would have been an unwelcome alliance; but to have it so clandestinely formed, and such a period chosen for its completion, placed Julia’s feelings in a most unfavorable light. He called it a bad thing, done in the worst manner, and at the worst time; and though he said that Julia was more pardonable than Maria, for folly was more pardonable than vice, he thought the step she had taken would, in all probability, lead to a conclusion like Maria’s: a marriage conducted in haste, with a man as unprincipled as Yates, was likely to lead to disaster; particularly as he believed Yates belonged to a wild set. I comforted my mother as best I could, and Fanny joined me in the task. I drew Fanny aside this evening, and gave her an opportunity to talk of her feelings but her heart was too full. She said nothing of Crawford, but only that she hoped he and Maria would soon be found, and that Yates might turn out to be less wild than we feared, and that Julia and he might be happy.

Sunday 14 May

A wet Sunday. The weather brought out all the gloom of my thoughts and this evening, unable to bear it any longer, I confided everything in Fanny. I had hoped to spare her; to say no more than she already knew, that there had been a break between Mary and myself; but I was drawn on by her kindness. I told her of the disastrous interview with Mary; that I had at last realized Mary’s true nature; that I had been foolish to be so blind.

‘If only she could have met with better people,’ I said. ‘The Frasers did her no good.’

‘She met with you,’ said Fanny quietly. ‘She had an example before her, if she chose to see it.’

‘You are such a comfort to me,’ I said, squeezing her small fingers gratefully in my own. ‘But I can still not believe she was so very bad. If she had fallen into good hands earlier... Perhaps if I had tried harder...’

She said nothing, but she soon left me, appearing again a few minutes later, bringing something with her. She put it into my hands. It was a letter to her from Mary.

‘I cannot read this,’ I said. ‘It is addressed to you.’

‘I cannot watch you blaming yourself any longer, and so I give you leave to read it,’ she said.

‘Indeed, I think you must.’

My eyes went to it almost against my will. It was dated some time before, shortly after Tom fell ill, and as I read it I felt a coldness creeping over me, chilling me to the bone.

From what I hear, poor Mr. Bertram has a bad chance of ultimate recovery. I thought little of his illness at first. I looked upon him as the sort of person to be made a fuss with, and to make a fuss himself in any trifling disorder, and was chiefly concerned for those who had to nurse him; but now it is confidently asserted that he is really in a decline, that the symptoms are most alarming, and that part of the family, at least, are aware of it. If it be so, I am sure you must be included in that part, that discerning part, and therefore entreat you to let me know how far I have been rightly informed. I need not say how rejoiced I shall be to hear there has been any mistake, but the report is so prevalent that I confess I cannot help trembling. To have such a fine young man cut of in the flower of his days is most melancholy. Poor Sir Thomas will feel it dreadfully. I really am quite agitated on the subject. Fanny, Fanny, I see you smile and look cunning, but, upon my honor, I never bribed a physician in my life. Poor young man! If he is to die, there will be two poor young men less in the world; and with a fearless face and bold voice would I say to any one, that wealth and consequence could fall into no hands more deserving of them. It was a foolish precipitation last Christmas, but the evil of a few days may be blot ed out in part. Varnish and gilding hide many stains. It will be but the loss of the Esquire after his name. With real affection, Fanny, like mine, more might be overlooked. Write to me by return of post, judge of my anxiety, and do not trifle with it. Tell me the real truth, as you have it from the fountainhead. And now, do not trouble yourself to be ashamed of either my feelings or your own. Believe me, they are not only natural, they are philanthropic and virtuous. I put it to your conscience, whether ‘Sir Edmund’ would not do more good with all the Bertram property than any other possible ‘Sir.’

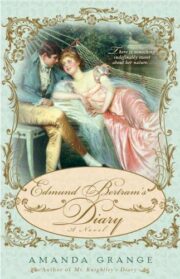

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.