I hoped this would make her think more kindly of him, for to remember her when all the pleasures of London were distracting him was a sign of no ordinary attachment. I told her of Maria:

There is no appearance of unhappiness. I hope they get on pretty well together — and Julia —

Julia seems to enjoy London exceedingly — and then Mansfield — We are not a lively party. You are very much wanted. I miss you more than I can express — before finishing with, Yours ever, my dearest Fanny.

I sealed the letter and my father franked it, then I went over to Thornton Lacey and saw what had been done to the house, before attending to parish business.

Tuesday 28 March

I made up my mind to it, and this morning I began my letter to Mary. I had scarcely written a line, however, when something happened which put everything else out of my mind. My father had a letter from a physician in Newmarket, telling us that Tom had had a fall, and that there was worse, for as a consequence of neglect and drink, the fall had led to a fever. Tom was on his own, for his friends had deserted him. I was alarmed, and said I would go to him at once. My father said he would write to my sisters and let them know the news. I travelled quickly, and now here I am in Newmarket, and not at all sanguine. Tom is much worse than I expected. He did not know me when I walked in to the room. His physician said he was not to be moved, and I agreed it must not be thought of.

I wrote to my father, but played down my fears, saying only that Tom was ill but that I thought he would soon be well enough to be brought home.

Thursday 30 March

Tom continued feverish and there was no chance of my taking him home, for he was too ill to be moved. I wished he would recognize me, but his eyes opened rarely, and when they did, I do not believe he saw anything at all.

APRIL

Saturday 1 April

There was some improvement in Tom’s condition today. The fever seemed less, and for the first time I felt there was hope, real hope, that he would recover.

Tuesday 4 April

Tom had a good night, and the physician said that, if his improvement continues, he will be well enough to make the journey to Mansfield tomorrow. I am more relieved than I can say. I want, more than anything, to have him safely home again.

Wednesday 5 April

The physician called again this morning and pronounced himself satisfied with Tom’s progress. I made arrangements for the journey, and once the carriage was as comfortable and warm as I could make it, I carried him downstairs and put him inside. He smiled weakly, and said it made a change to have me carrying him when he was ill and not drunk, and I smiled, too, but my smile was no stronger than his. I was seriously worried, for he weighed nothing at all. I wrapped him about with blankets and then we set off. The journey was good and the weather fine, but he became progressively weaker as the day went on, and he was feverish again by the time we arrived.

Mama was horrified at the sight of him, and to be sure he looked very ill when he was carried into the house, for he was white and sweating, and he was delirious. My father looked very grave and Tom was quickly got to bed whilst our own physician was sent for. He did all he could for him, and now we must trust to the fact that Tom is at home, where he can be properly cared for, to bring him about.

Monday 10 April

Julia has offered to come home if we have need of her, but there is nothing she can do, and my father thinks she is better where she is. I wrote to her directly, telling her that she need not come home at present. She has not seen Maria recently, for Maria is spending Easter with the Aylmers at Twickenham whilst Rushworth has gone down to Bath to fetch his mother. Julia has seen Mary, though, and has told her of Tom’s illness. I wish I had more time to think of Mary, but with Tom so ill, I can think of nothing else. And perhaps it is a good thing, for I am worn out by asking myself if Mary will have me or not.

Wednesday 12 April

Tom is out of danger, thank God, and Mama is at last made easy. It has been a terrible week for her, seeing Tom laid so low. But the fever has subsided, and we have encouraged her to think that, now it has gone, Tom will soon be well. She smiled again for the first time since she heard of Tom’s fall, and she wrote to Fanny straightaway, to tell her that he was much improved. I do not know what she would have done without Fanny this week, for although Fanny is not here, her presence is everywhere felt. Mama has found it a comfort to write to her every day, sharing her hopes and fears, and my father is grateful for it. But today I felt compelled to write my own letter to Fanny, to let her know the real state of affairs, for although Tom’s fever has subsided there are some strong hectic symptoms which we are keeping from Mama. The physician cannot say which way things will go. They may go well, in which case Tom will make a full recovery, but if they go badly, there is a danger to his lungs. all we can do now is watch and pray, and hope Tom’s youth and vigor will see him through.

Thursday 13 April

I sat with Tom again this morning and he felt strong enough to talk, saying, ‘What a fool I have been, Edmund.’

‘Nonsense. Your spirits are low. You will soon be well again, and then you will think yourself a very clever fellow,’ I said.

He laughed at this, but his laugh turned to a cough which tired him and so I refrained from talking to him afterwards, instead bidding him to lie quietly and conserve his strength. I was about to leave his room when he restrained me with a feeble hand, saying, ‘Stay. It does me good to have you here. My father is too loud, and my mother too tearful. You are the only one I can stand.’

And so I sat beside him again, glad to be of use.

Friday 14 April

Tom seemed a little stronger today, and I read to him.

‘What? Not The Rake’s Progress?’ he asked, as I took up the book. It was good to hear him joking, and I pray he may soon be well. If the hectic symptoms abate, then there is every chance of it. And with the better weather coming, it will be possible for him to sit in the garden and make a full recovery at his leisure.

MAY

Monday 8 May

Just as one problem is abating, another has presented itself, for my father received a letter this morning which agitated him immensely. I thought at first it must be news of more illness, but he reassured me; saying, however, that he must go to London at once. He left me in charge of the estate and told me not to leave Mansfield in case he needed me. He was just about to depart when another letter came by express. As he opened it he let out a cry and sat down. His eyes passed rapidly over the hasty scrawl and when he had finished he sat as though stunned.

‘What is it?’ I asked.

He did not reply, but sat staring in front of him with unseeing eyes.

‘You are ill!’ I said, going to him in alarm.

But he waved me away.

‘No,’ he said, passing a hand over his eyes. ‘I have had a shock, that is all. But what a shock!

Edmund, I am going to need your help. These letters are from one of my oldest friends. The first revealed that there was some gossip about Maria and Mr. Crawford, and that it would be well for me to go and see her, for her husband was uneasy. I was displeased, but not unduly alarmed, for it seems that Maria and Crawford met at Twickenham; an innocent enough occurrence, as Crawford’s uncle has a cottage there; and this fact, coupled with Rushworth’s absence, would be enough for many an idle person to gossip about. But his second letter, come just now, is much worse. Here You had better read it.’

He handed it to me, and I read it quickly, and with growing horror. Maria had run away, and Mr. Harding, my father’s correspondent, feared that there had been a very flagrant indiscretion. He was doing all in his power to persuade Maria to return to her home in Wimpole Street, but he was being obstructed in this by Rushworth’s mother, who did not want her back, for it appeared the two of them had never liked each other.

My father had by this time recovered himself and strode to the door. I offered to go with him, and before long, having communicated what was necessary to the rest of the family, we set off. We arrived in London late this evening, but Maria’s flight had already been made public beyond hope of recovery. We called briefly at Wimpole Street, where Rushworth and his mother were loudly lamenting the fact, and as there was nothing to be gained by staying there, we went next to Crawford’s uncle’s house. Crawford had already left, as if for a journey, and there could no longer be any doubt that Maria had run off with him.

I thought of Fanny, and her idea that there had been something between Maria and Crawford. She had suspected his liking for Maria, and she had been wary of him because of it. I had told her she was wrong, but it was I who had been wrong.

Poor Fanny! As soon as I began to grow used to Maria’s shame, I saw that she, too, was a sufferer in this, for Fanny had lost the man who had offered her marriage, the man to whom she had been almost engaged.

I felt the blow deeply. For us to suffer did not seem too terrible, for we were strong enough to bear it, but for Fanny to suffer cast me down, and I resolved to go to her as soon as I could. But it could not be at once, for there was still much to be done. My father suggested next that we go and see Julia, who was staying with her cousins, to reassure her that we were in town, and that we were doing all we could to save her sister. But when we reached the house, another calamity hit us, for the house was in turmoil. My father’s cousin went ashen when he saw us, and invited my father into his study. My father emerged a few minutes later to tell me that Julia had eloped!

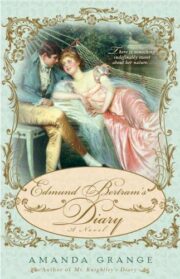

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.