‘I will be going to town in less than a fortnight,’ I said to Fanny, when my father and I rejoined the ladies. ‘Do you have any commissions for me?’

‘I cannot think of anything at the moment.’

‘You must let me know if any occur to you. And if you have any letters for Miss Crawford I can take them to her.’

‘You will be visiting her?’ she enquired.

‘Yes, indeed. I am looking forward to it. I am persuaded that she, too, is looking forward to it. She will be able to hear about you, and everyone at Mansfield.’

Fanny said nothing.

‘You are very quiet, Fanny. Have you nothing to say of your friend? I thought you would be constantly talking of her. It cannot be pleasant for you to be all alone again.’

‘I have my aunts, and—’

‘And?’

‘And... that is enough.’

My mother calling to me, I could say no more, but as Mama was happy to talk of Mary, I was well satisfied with my evening, and could only have enjoyed it more if Fanny had confessed to missing Crawford as much as I missed his sister.

Wednesday 18 January

I spoke to Ingles about the field and although he said he did not want to sell, and could not let it go below an exorbitant price, I believe he was only bargaining and will let me have it in the end.

Monday 23 January

Fanny’s indifference to Crawford’s and Mary’s absence has been made clear: she is too excited at William’s visit to have room in her mind and heart for anything else. He is to join us on Friday, and I hope that seeing him, newly promoted, will make Fanny think more kindly of Crawford, whose good offices brought the promotion about.

Friday 27 January

William arrived, looking bright and handsome, and was full of his new honor. He lamented the fact that he could not show his uniform to us, but he described it in enough detail to please even Fanny. I wished she could see it, but I fear that, by the time she does, it will no longer be a source of such joy to William. A lieutenant’s rank will satisfy him for now, but before long he will want further promotion; his uniform will seem like a badge of disgrace when all his friends have been made commanders. I only hope that by then, Fanny will be safely married to Crawford, and that the Admiral will be disposed to help William again. That would be a happy occasion indeed, if we could see William in a captain’s uniform. I said as much to Fanny, and she smiled, and said she was sure his merits would lift him to the highest rank. It transpired that Fanny will settle for nothing less than seeing him an admiral!

Saturday 28 January

Crawford left a horse for William to ride and we went out together this morning. We had not gone far before he had a fall. Having ridden mules, donkeys and scrawny horses he was not adept at handling a highly bred animal, and came to grief whilst jumping a fence. The horse was none the worse, which was a mercy, or Crawford would have paid a heavy price for his kindness. William was unhurt, but he bruised his side and his coat was covered in mud.

‘Say nothing of this to Fanny,’ he begged me. ‘She worries about me; though if she could see the scrapes I have survived she would know I could survive anything! On my first ship I was swept overboard and was only able to climb back again by grabbling hold of a piece of torn sail that had washed overboard with me. By luck it was still attached to the rest of the sail, and I used it as a rope to haul myself in.’

The stories became more gruesome; far worse than the ones he had told in the drawing-room; and I was glad he had spared Fanny the details of his hardships and deprivations, and the rigors of Navy life. I admired him all the more for being so considerate, as well as for being a brave man.

‘We can go to Thornton Lacey,’ I said. ‘You can wash there and brush your coat when the mud has dried. I can lend you a shirt,’ I added, noticing his own was ripped, for luckily I had begun to move some of my things over to the rectory.

We were soon there and I took him into the kitchen so that he could wash. As he stripped off his shirt I saw there were a number of scars on his back and arms and he told me about each one; how a Frenchman had got in a lucky thrust as he boarded a foreign vessel; how he had been outnumbered and had had to fight his way out of a corner with his sword in his left hand; how he had been down, with a sword at his throat, when his friend had run his adversary through, and he had taken a cut when his adversary fell. And tales of a better sort: the deep scar on his right arm had come from his standing between his captain and injury; and the scar on his shoulder was from protecting the cabin boy, a young lad on his first voyage, who, because of William’s prompt action, had survived to make a second one.

I gave him a clean shirt and once the mud had dried he was able to brush it from his coat before we returned to the Park. We found Fanny in the drawing-room, sketching.

‘I am glad to see you have taken Mary’s advice,’ I said, when I saw the fruit of her labors; explaining to William, ‘Fanny’s friend, Miss Crawford, advised her to have a picture of you to keep by her when you are away.’

‘Now that I have my promotion, it is perhaps worth having, ’ he acknowledged.

‘It was always worth having, to me,’ said Fanny.

‘You should draw a likeness of Edmund,’ said William. ‘Your sketching is really very good. Is it not?’ he asked me.

‘Yes, excellent. well, Fanny? will you draw me?’

‘If you will still for as long as it takes, and not be off on parish business.’

‘I believe it can spare me for the rest of the day.’

William stood by Fanny’s shoulder as she drew, saying, ‘A little more length here,’ or ‘a little more shading there,’ until it was done.

‘Very creditable,’ I said. ‘I will have it framed, I believe, the next time I go into town.’

‘And perhaps, the next time I see you, you can sketch me in my new uniform as well,’ said William.

Monday 30 January

My father was impressed with Fanny’s drawings, and he has thought of a scheme to help her see William in his new uniform.

‘I am planning on sending her back to Portsmouth with him, to spend a little time with her family,’ he said to me. ‘What do you think of the idea, Edmund?’

‘I think it an excellent one. I know she will welcome it.’

‘Good. Then send her to me and I will tell her of it,’ he said. When Fanny heard of it she was in raptures. Though she did not make the noise my sisters would have done at such delight, her shining face told me her feelings, and her swelling heart soon gave them voice.

‘I can never thank my uncle enough for being so kind,’ she said to William and me. ‘To go home again! And to be with you, William, until your very last hour on land. And then to stay with my family for two months, perhaps three. Oh! never was anyone luckier than I.’ Then her face fell and she said to me, ‘But will your mother be able to manage without me?’

‘Of course she will,’ I said. ‘She will have Aunt Norris.’

‘But Aunt Norris will not fetch and carry for her as I do.’

‘Then I will do it for her.’

‘But you will not be here.’ She colored. ‘You will soon be going to town, and you will have other demands on your time, other people...’

I thought of Mary, and I was sure her thoughts had gone to Mary’s brother, for why else should she fall silent? I reassured her that Mama would manage without her, but she was still perturbed, and it was not until my father reassured her after dinner that she was content. It is so like Fanny to be always thinking of others. It will do her good to go to Portsmouth, where she can think more of herself. And if she marries Crawford — when she marries Crawford — she will be able to consult her own inclination on almost everything. She will have servants to run her errands, instead of having to run them for others, and everything in the house will be organized as she wishes. She will be a very happy woman before the year is out.

Tuesday 31 January

Having told Fanny Mama could manage without her, I was surprised to find that Mama saw it in a different light.

‘Why should she see her family?’ she asked, when Fanny was out riding. ‘She has done very well without her family for eight or nine years. Why can she not do without them again?’

‘My dear,’ said my father, ‘it is only right and proper that Fanny should visit them from time to time.’

‘I do not see why,’ said Mama, picking Pug up and stroking him. ‘I am sure she does not want to go. Ask her, Sir Thomas. I am sure she would much rather stay here.’

‘She has a duty to her family,’ said my father, trying again.

‘And she has a duty here,’ returned Mama.

‘It will be a sacrifice for you, I know,’ said my father, ‘but Lady Bertram has always been capable of sacrifice for the good of others, and I know she will be so again.’

This courtesy did little to soften Mama’s unhappiness. ‘I see that you think she must go, and if you think it, Sir Thomas, then she must, but for myself I can see no reason for it. I need her so very much here.’

At this my aunt joined in the conversation.

‘Nonsense, my dear Lady Bertram. Fanny can very well be spared. I am ready to give up all my time to your pleasure, and Fanny will not be wanted or missed.’

‘That may be, sister. I dare say you are very right; but I am sure I shall miss her very much,’ said Mama.

Knowing that my father would have his way and Fanny would go to Portsmouth, I blessed Mama for her words; it was good to know that Fanny would be so missed by someone other than myself, for I fear she is often taken for granted.

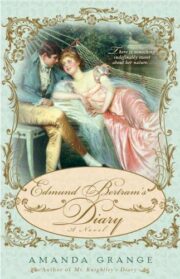

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.