I smiled to see her so well entertained, and by such an agreeable man. I was about to speak to Mary when Dr Grant claimed my attention.

‘About your living, Edmund,’ he said. ‘You will be ordained at Christmas, I believe?’

‘Yes, that is so. I will be going to stay with my friend Owen and we will be ordained together.’

‘And you will then come into the living. well, it is not a bad living, the one at Thornton Lacey...?’

‘Seven hundred pounds a year.’

‘Just so. Not a bad living. But it could be improved.’

He gave me the benefit of his advice, and once we had finished our discussion, Crawford said, ‘I shall make a point of coming to Mansfield to hear you preach your first sermon. I shall come on purpose to encourage a young beginner. When is it to be? Miss Price, will not you join me in encouraging your cousin? will not you engage to attend with your eyes steadily fixed on him the whole time — as I shall do — not to lose a word; or only looking off just to note down any sentence preeminently beautiful? We will provide ourselves with tablets and a pencil. When will it be? You must preach at Mansfield, you know,’ he said to me, ‘that Sir Thomas and Lady Bertram may hear you.’

‘I shall keep clear of you, Crawford, as long as I can,’ I said with a wry smile, for he would be sure to disconcert me.

The party broke up, and I am persuaded Fanny enjoyed her evening in company, and will have many more such evenings to come.

DECEMBER

Friday 2 December

Business taking me up to town, I called in to the jewelers and ordered a gold chain for Fanny. Now that she is going out and about she will need some adornment, and it will give me great pleasure to give her such a gift. I looked at a variety but in the end I chose a simple chain so that she will be able to wear it on any occasion. I asked for it to be shortened as it was rather long for her and I was told it would not be ready until I had left town. When I called on Tom, I asked him if he would collect it for me. He promised to do so, and to send it on to me at Mansfield.

He was in good spirits. He asked me if I had proposed to Mary yet, and when I shook my head he said I was making slow work of it.

‘I want to find you all married the next time I come home: you, Fanny, Julia — and Aunt Norris!’

I could not get a serious word out of him, but it was good to see him again, all the same.

Monday 5 December

Fanny and I dined at the Parsonage again this evening, and on Fanny happening to mention her brother, Crawford continued to draw her out by asking her all about him.

‘William is on the Antwerp, you say?’ he asked, drawing his chair closer to hers.

‘Yes,’ said Fanny.

‘And you are longing to see him again, no doubt,’ he said with a smile. ‘You have been parted for a very long time.’

‘Oh, I have. I would like to see him again above anything. I wish I knew when he was coming home.’

‘I will ask my uncle. Admiral Crawford will know, or if he does not, then some of his connections at the Admiralty will be able to find it out. The Antwerp is in the Mediterranean, you say?’

‘Yes, or at least it was, the last time I heard.’

‘Well, it is not so very far from there to here. I am sure he will be home again soon. will you see him when he is?’

‘I hope so.’

‘And so do I, for I can tell how much you miss him.’

They continued in similar vein, and I thought how very good it was of Crawford to take such an interest in William, for if there was anything guaranteed to please Fanny, it was someone’s taking an interest in her brother.

I said as much to Mary, who remarked satirically, ‘Oh yes, Henry is always able to please young ladies.’

‘And I...’ I caught myself, as she looked at me expectantly, and I realized I had almost asked if I could please them, too... ‘will be very glad to see William, too.’

‘Ah, yes, I am sure you must be longing for a visit from him quite as much as Fanny,’ she said, laughing at me.

I was bewitched, and wondered again if I had any chance of being accepted by her. If her smiles were anything to the point, then yes. But if her professions of a desire to be rich were to be taken seriously, then no.

I was no closer to understanding her when the evening came to an end.

Tuesday 6 December

As sometimes happens in life, talking about a thing has brought it on, for Fanny had a letter from William this morning.

‘Well, Fanny, are you not going to tell us your news?’ I asked her, as I saw her bright eyes, and knew it must be good. ‘Do not keep us in suspense!’

‘The Antwerp has returned. William is home!’

‘I wondered why the letter was so short!’ I said with a smile. She smiled back at me, for William’s letters are usually exceedingly long.

‘He had time for no more than a few lines, written as he was coming up the Channel. He sent the letter in to Portsmouth with the first boat that left the Antwerp when she lay at anchor.’

‘The first boat? I would expect nothing less!’

‘That is very good news,’ said my father kindly. ‘You will like to see him, I am sure. There will be no difficulty in his obtaining a leave of absence.’

‘No, none at all. It is one of the advantages of being a midshipman, ’ she agreed.

‘Then we must invite him here. Fanny, you must write to him. I will dictate the letter myself.’

Fanny furnished herself with pen and paper, and I could not help remembering the first letter she had written to William, blotted with tears, and strangely spelt. As I watched her even hand flow over the paper, I thought how much she had grown, not just in stature but in person, and how graceful she had become over the years.

She was in the middle of the letter when Crawford strolled up from the Parsonage, carrying a newspaper.

‘My dear Miss Price, what do you think? As I turned to the ship news this morning, I saw that the Antwerp had docked, so I came at once to give you the news.’

‘I know,’ she replied, looking up from her letter. ‘I have had a letter from William this morning.’

‘Ah! I had hoped to be the first to tell you. But I cannot be sorry you have had it already, when I see how much pleasure it brings you. I have never seen you looking happier.’

‘You are too kind. And it was very thoughtful of you to bring me the paper,’ she said, ‘for if I did not already know, it would have delighted me beyond anything.’

‘Then I am rewarded for my small trouble,’ he replied with a bow. The letter was finished, and Crawford suggested we go out for a ride. I asked if Miss Crawford might like to come with us, but she was indisposed, and so the three of us went out together. When we had done, Fanny and I returned to the Parsonage with Crawford, and I asked after Miss Crawford. She was better, but her head still ached, Mrs. Grant said. I sent her my good wishes, and after lunch I repaired to the study where my father and I talked over estate business until dinner.

The table seemed lifeless without Mary. I have come to depend on her presence, and the liveliness of her company; a liveliness I am increasingly unwilling to live without.

Friday 9 December

Fanny could not settle to anything all day, so busy was she watching for William’s arrival. I came across her in the lobby, in the hall and on the stairs, her eyes looking out of the window, and her ears straining for the first sound of a carriage. At last she repaired to the drawing-room and took up her needlework, though I believe very few stitches were laid, for every time a step came on the gravel she jumped up, and if she heard a horse whinny she ran to the window.

‘He cannot be here before dinner,’ I told her.

‘If he has a good journey he could be here by four o’clock,’ she said.

‘You have measured the distance?’ I asked her teasingly.

She said with a smile, ‘I have been looking at the map.’

She sat down again, and picked up her needlework.

‘What a lucky boy William is, to be sure, to have had so much help from Sir Thomas,’ said my aunt, as Fanny’s eyes went every few minutes out of the window. ‘I hope he is properly grateful for all the help he has received, for without it he would not have done half so well.’

‘I did very little,’ said my father kindly. ‘He has worked hard and made the most of his advantages. I gave him his start, perhaps, but he has progressed on his own merits.’

My aunt continued in a similar vein until, hearing the carriage, she said, ‘There he is! What a day this is, to be sure! How happy he will be to be here, in the house of his benefactor. I must go and welcome him at once.’

‘Pray, do not stir yourself,’ said my father, as Fanny ran out of the room, ‘for I am sure there is no need.’

‘But Sir Thomas, there is every need in the world,’ she said, eager to be doing something.

‘It is cold in the hall, you had much better remain by the fire,’ I said to her, for I was determined to give Fanny some time alone with William before she had to share him with others.

‘I have never been one to worry about a little cold, when there is a duty to perform,’ said my aunt. ‘Indeed, where would we all be if we allowed such trifles to prevent us from doing what we knew to be right?’

As she stood up, my father spoke, and I realized we had the same idea.

‘Mrs. Norris, I need your advice,’ he said. ‘Do you think I should have the fire built up? It is, as Edmund so rightly says, cold today. Do you think we should have more coal on the fire, or will we grow too hot?’

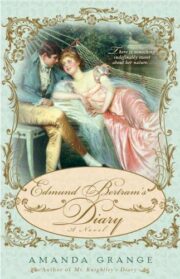

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.