‘How quiet we are without them,’ Mama observed sadly after dinner. She turned to Fanny, who was sewing quietly, her needle flashing as her small white fingers did their work. ‘Fanny, my dear, put your work aside and come and sit next to me on the sofa.’

Fanny did as she was bid and was soon sitting with Mama, who gave her Pug to hold as a mark of the highest approbation.

Monday 21 November

If my sisters’ departure has done one thing, it has given Fanny more chance of coming forward, and for this I am very glad.

She went into the village this morning on an errand and as it happened to come on to rain when she passed the Parsonage she was asked inside. Miss Crawford provided her with dry clothes and then entertained her until the rain ceased. It was just like Mary to be so considerate and I am sure Fanny enjoyed herself immensely.

I have seen little of Mary since the play. Perhaps it is a good thing, as the rehearsal brought forth feelings that should have been left buried, for I have nothing to offer an heiress and it would be folly for me to think of her except as a dear friend. And yet... and yet... once I am ordained I will have a house and an income, and I cannot help remembering her face as she said to me, ‘I’ll marry.’

‘I am very glad the rain stopped before too long,’ said Fanny, ‘for Dr Grant threatened to send me home in the carriage otherwise.’

I smiled at her use of the word threatened. Anyone else would have said promised.

‘And why should he not, Fanny? It is only what any gentleman would do for a neighbor. You must learn to think more of yourself, for I assure you, we all think very highly of you. And so Miss Crawford played the harp for you, did she?’

‘Yes, she did.’

‘And did you not think her a most superior performer?’ I asked. At which Fanny agreed that Miss Crawford was indeed a superior performer, and before very long we had agreed that she was a superior young woman in every way.

Monday 28 November

Fanny’s intimacy at the Parsonage continues and this afternoon, my mother wanting her, I walked to the Parsonage to find her. Mrs. Grant took me out into the shrubbery, where Fanny and Mary were sitting. Their being together was exactly what I wished to see, for they will do each other good, Fanny by losing some of her shyness, and Miss Crawford by having a friend of sense and intelligence.

‘Well,’ said Miss Crawford brightly when she saw me, ‘and do you not scold us for our imprudence in sitting out of doors so late in the year?’

‘I have been too busy with the housekeeping to be alarmed by anything else,’ said Mrs. Grant with a sigh.

Miss Crawford laughed, declaring she would never have any such grievances.

‘There is no escaping these little vexations, Mary, live where we may,’ said her sister. ‘And when you are settled in town and I come to see you, I dare say I shall find you with your vexations, just as I have them in the country.’

‘I mean to be too rich to lament or to feel anything of the sort,’ said Mary. ‘A large income is the best recipe for happiness I ever heard of.’

‘You intend to be very rich?’ I asked.

‘To be sure. Do not you? Do not we all?’ she asked.

‘I cannot intend anything which it must be so completely beyond my power to command. Miss Crawford may choose her degree of wealth. She has only to fix on her number of thousands a year, and there can be no doubt of their coming,’ I said, my spirits sinking, for she could win the heart of any man she had a mind to, I was sure. ‘My intentions are only not to be poor.’

‘By moderation and economy, and bringing down your wants to your income, and all that,’ she said lightly. ‘I understand you — and a very proper plan it is for a person at your time of life, with such limited means and indifferent connexions. What can you want but a decent maintenance?

You have not much time before you; and your relations are in no situation to do anything for you, or to mortify you by the contrast of their own wealth and consequence,’ she went on satirically. ‘Be honest and poor, by all means, but I shall not envy you; I do not much think I shall even respect you.’ She gave an arch smile. ‘I have a much greater respect for those that are honest and rich.’

‘Your degree of respect for honesty, rich or poor, is precisely what I have no manner of concern with,’ I said, answering her in a similarly lighthearted tone. ‘I do not mean to be poor. Poverty is exactly what I have determined against. Honesty, in the something between, in the middle state of worldly circumstances, is all that I am anxious for your not looking down on.’

‘But I do look down upon it, if it might have been higher. I must look down upon anything contented with obscurity when it might rise to distinction.’

‘But how may it rise?’ I asked her. ‘How may my honesty at least rise to any distinction?’

She thought. ‘You ought to be in parliament, or you should have gone into the army ten years ago.’

‘That is not much to the purpose now; and as to my being in parliament, I believe I must wait till there is an especial assembly for the representation of younger sons who have little to live on. No, Miss Crawford,’ I went on more seriously, for she was looking very pretty and I thought that any man who could win her would be fortunate indeed, ‘there are distinctions which I should be miserable if I thought myself without any chance — absolutely without chance or possibility of obtaining — but they are of a different character.’

She laughed at me, but it was a laugh of friendship and not derision, so that, despite her words, I felt there was hope. Satisfied, I recollected that I had come to collect Fanny, and we made our adieus.

On the way out we were met by Dr Grant, who invited us to dinner tomorrow, and, being grateful to the Grants for taking notice of Fanny, I accepted for both of us. Then Fanny and I walked home together.

Wednesday 30 November

‘I am very glad the Grants thought of inviting you,’ I said to Fanny, when, at twenty past four this afternoon, we went down to the Parsonage in the carriage. ‘I knew how it would be. Now that my sisters are away, our neighbors are starting to realize that you are not a girl any longer, but a young woman, and I am sure more invitations will follow this one. I must look at you, Fanny, and tell you how I like you. As well as I can tell by this light, you look very nicely indeed. What have you got on?’ I asked her, for indeed the winter twilight was so dim I could scarcely tell.

‘The new dress that my uncle was so good as to give me on my cousin’s marriage. I hope it is not too fine; but I thought I ought to wear it as soon as I could, and that I might not have such another opportunity all winter.’

‘A woman can never be too fine while she is all in white. Besides, it is your first dinner invitation, and so it is a special occasion.’

As we passed the stable yard I saw a carriage.

‘Who have they got to meet us?’ I said. I let down the side-glass to have a better look. ‘It is Crawford’s barouche. This is quite a surprise, Fanny. I shall be very glad to see him.’

Fanny was distinguished as we went in, and she was fussed over in a way that, whilst it confounded her, delighted me. I will be happy indeed when she can take these little attentions as a matter of course, for then my little Fanny will have truly grown up and taken her natural place in the world.

Conversation flowed easily, and Crawford entertained us all with tales of his stay in Bath.

‘I am glad to have you back, Henry, my boy,’ said Dr Grant, wiping tears of laughter from his eyes after one of Crawford’s anecdotes. ‘You must stay awhile.’

‘But I have to return to my own estate,’ said Crawford.

‘Nonsense! It can manage without you a little longer. What do you say, Mary?’

‘Yes, Henry, do stay,’ Mary urged, with the most pleasing sisterly affection.

‘I have nothing here...’ said Crawford.

‘What does that signify?’ said Dr Grant. ‘You can send for your hunters.’

‘Nothing would be easier,’ I said, thinking how lucky we would be to have another gentleman for company over the winter, especially one as well informed, and agreeable to the ladies, as Crawford.

‘And what say you, Miss Price?’ asked Crawford, turning to Fanny. I blessed him for bringing her forward, for she was inclined to be silent, overawed by so much company.

She flushed and said nothing.

‘Do you think this weather will last?’ he persevered.

‘I cannot say,’ she returned in confusion.

‘Should I send for my hunters?’

‘I really do not think I can give an opinion,’ she said.

‘Well, then,’ said Crawford, continuing with the breeding and kindness of a true gentleman, ‘do you think I should stay?’

‘It is not for me to say.’

‘But you would not dislike it?’

‘No,’ she said, when pressed. ‘I should not dislike it.’

‘Then it is settled.’

He smiled at her, and Fanny managed a small smile in return, and though it was no more than civility demanded I was glad she had managed so much.

My sisters were, of course, mentioned. After dinner, Crawford spoke of Maria’s marriage, saying, ‘Rushworth and his fair bride are at Brighton, I understand?’

Mary drew Fanny into the conversation with quite as much kindness as her brother, saying,

‘Yes, they have been there about a fortnight, Miss Price, have they not? And Julia is with them.’

‘How we miss them. You were Mr. Rushworth’s best friend,’ he said to Fanny. ‘Your kindness and patience can never be forgotten, your indefatigable patience in trying to make it possible for him to learn his part. He might not have sense enough to estimate your kindness, but I may venture to say that it had honor from all the rest of the party.’

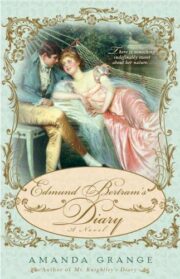

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.