There was so much argument I began to breathe easily again, for I thought they would argue so much over the play that nothing would come of it after all. But in this I was mistaken, for when we were in the billiard room this evening, Tom declared it to be the very size and shape for a theatre.

‘If we move the bookcase away from the door in my father’s room, it can be made to open, and as it will then communicate with our theatre in the billiard room we can use it as a greenroom.’

‘You are not serious?’ I asked him.

‘Not serious! Never more so, I assure you. What is there to surprise you in it?’

‘We cannot make free with my father’s room,’ I objected.

‘Why not? What does it matter, when he is not here to see it?’

My thoughts ran to wine stains on the carpet, white rings on the desk — for I believed Yates to be capable of putting a hot cup down on the polished wood — and all the attendant evils of carelessness, but Tom would not listen.

I spoke to him of our reputation and our father’s absence but he only said, ‘Pooh! You take everything too seriously, Edmund. Anyone would think we were going to act three times a week till my father’s return, and invite all the country! And as to my father’s being absent, it is so far from an objection, that I consider it rather as a motive; for the expectation of his return must be a very anxious period to my mother; and if we can be the means of amusing that anxiety, and keeping up her spirits for the next few weeks, I shall think our time very well spent, and so, I am sure, will he. It is a very anxious period for her.’

As he said this, we looked towards our mother who, sunk back in one corner of the sofa, the picture of health, ease, and tranquility, was just falling into a gentle doze. I could not help giving a wry smile, and Tom had the grace to laugh.

‘By Jove! this won’t do,’ he cried, throwing himself into a chair. ‘To be sure, my dear mother, your anxiety — I was unlucky there.’

‘What is the matter?’ she asked, half-roused. ‘I was not asleep.’

‘Oh dear, no, ma’am, nobody suspected you! well, Edmund, ’ he continued, ‘but this I will maintain, that we shall be doing no harm.’

Nothing I could say would sway him; no concern for Maria and Julia’s reputations, for if word of it got out they would be regarded as fast; nor considerations of our father’s wishes, for he would surely not wish us to take such liberties with his house whilst he was away; nor thoughts of the upheaval and expense.

‘I know my father as well as you do; and I’ll take care that his daughters do nothing to distress him. Manage your own concerns, Edmund, and I’ll take care of the rest of the family,’ he said.

‘Don’t imagine that nobody in this house can see or judge but yourself. Don’t act yourself, if you do not like it, but don’t expect to govern everybody else.’

He walked out of the room and I sat down by the fire, feeling exceedingly low, for I was sure one thing would lead to another and I feared that, before long, we would find ourselves embroiled in a major undertaking. And I was responsible, for I had promised my father I would look after affairs in his absence. What would he feel if he returned to find the profits of the estate spent on something so frivolous, when he had just spent two years in Antigua in an effort to mend the family fortunes?

Fanny followed me and sat down beside me.

‘Perhaps they may not be able to find any play to suit them. Your brother’s taste and your sisters’ seem very different, ’ she said.

‘I have no hope there, Fanny,’ I said with a sigh. ‘If they persist in the scheme, they will find something. I shall speak to my sisters and try to dissuade them, and that is all I can do.’

She agreed that this would be my best choice of conduct. Tomorrow, then, I must try to dissuade my sisters from acting, and hope it puts an end to the scheme.

Friday 23 September

I did my best to dissuade Maria and Julia from putting on a play this morning, but they would not listen to me.

‘Of course the estate can bear the expense,’ said Maria.

‘I am persuaded Rushworth would not like you to act,’ I said, trying to sway her.

‘He must learn I have a mind of my own,’ she returned.

Julia was no easier to persuade, for although she thought Maria had better not act, as for herself, there could be no objection to it.

At that very moment Henry Crawford entered the room, fresh from the Parsonage, calling out,

‘No want of hands in our theatre, Miss Bertram. No want of understrappers: my sister desires her love, and hopes to be admitted into the company, and will be happy to take the part of any old duenna or tame confidante, that you may not like to do yourselves.’

Maria looked at me as much as to say, ‘Can we be wrong if Mary Crawford sees no harm in it?’

I was obliged to acknowledge that the charm of acting might well carry fascination to the mind of genius; and to think that Miss Crawford, as ever, was the most obliging young woman. She, at least, was blameless, for she did not know how my father’s affairs stood, and could not be expected to know that any additional expense, coming at such a time, was very undesirable. My aunt expressed a few reservations when Tom told her of the scheme and I hoped, briefly, that this would dampen his enthusiasm, but he and Maria joined forces and soon talked Aunt Norris out of her objections, and the play became a settled thing. I must now make it my concern to limit the scope of the production so that it does as little harm as possible.

Saturday 24 September

Tom lost no time in calling the estate carpenter to the house, despite the fact that Jackson was needed to finish mending the fences blown down in last week’s strong winds. Tom told him to take measurements for a stage.

‘And when you have done, there is a bookcase in my father’s room that needs moving,’ he said. I reminded Jackson about the fence, and bid him see to it as soon as he was free, but if Tom is to continue as he has begun, he is going to make my life very difficult over the weeks to come.

‘And now for the baize. Where are we to get it, Aunt?’ asked Tom.

‘Had you better not wait until you have decided on a play?’ I asked him.

‘Details,’ he said, with a wave of his hand.

‘You must send to Northampton,’ said Aunt Norris. ‘They have quite the finest baize in the county; I saw it there the last time I went. It was of a superior quality, and they had just the shade we are looking for.’

Friday 30 September

The green baize has arrived, my aunt has cut out the curtains and the housemaids are busy sewing them, but no play has as yet been decided upon. At least I have had the fences repaired, for I forbade Christopher Jackson the house until the work was done.

OCTOBER

Monday 3 October

A play has been decided on at last, the worst play imaginable. If I had been there I would have spoken against it, but I was out for the day, and knew nothing about it until I returned just before dinner, when Rushworth told me the news.

‘It is to be Lovers’ Vows. I am to be Count Cassel, and am to come in first with a blue dress and a pink satin cloak,’ he said. ‘And afterwards I am to have another fine fancy suit, by way of a shooting-dress. I do not know how I shall like it. Bertram is to be Butler, a trifling part, but a comic one, and it is comedy he wants to play. And Crawford is to be Frederick.’

I was dumbstruck. Lovers’ Vows! With all its embracing and clasping to bosoms! The last play my father would want in his house!

‘But what do you do for women?’ I asked, knowing that my sisters could not play the parts, for Agatha was a fallen woman and Amelia was a shameless one.

Maria blushed in spite of herself as she answered, ‘I take the part which Lady Ravenshaw was to have done, and...’ she lifted her eyes to mine instead of letting them drop to the floor. ‘Miss Crawford is to be Amelia.’

I could not believe it. To condemn Miss Crawford to such a part! It was not worthy of her. And for Maria to play Agatha!

‘I come in three times, and have two-and-forty speeches,’ said Rushworth. ‘That’s something, is not it? But I do not much like the idea of being so fine. I shall hardly know myself in a blue dress and a pink satin cloak.’

I could not think how Tom had allowed it. I could say nothing in front of Yates, as his friends had been about to perform it at Ecclesford, but later I remonstrated with Maria.

‘My dear Maria, Lovers’ Vows is exceedingly unfit for private representation, and I hope you will give it up. I cannot but suppose you will when you have read it carefully over. Read only the first act aloud to either your mother or aunt, and see how you can approve it. Agatha is a fallen woman. She is seduced by her lover and left with child. You cannot play such a part. You cannot pretend to have been seduced, you cannot speak of fervent caresses, or embrace the man who plays your son, pressing him to your breast. You would not want to do such a thing, especially not now you are engaged. Only read the play, and it will not be necessary to send you to your father’s judgment, I am convinced.’

‘We see things very differently,’ said Maria uncomfortably. ‘I am perfectly acquainted with the play, I assure you; and with a very few omissions, and so forth, which will be made, of course, I can see nothing objectionable in it; and I am not the only young woman you find who thinks it very fit for private representation.’

‘You are Miss Bertram. It is you who are to lead. You must set the example.’

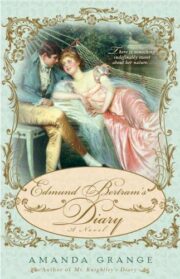

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.