Fanny agreed, for if Miss Crawford had had better friends and relatives, it was clear to both of us that her opinions would have matched our own.

We remained by the window and looked out into the darkening night. all that was solemn and soothing and lovely appeared in the brilliancy of the unclouded sky, and the contrast of the deep shade of the woods.

‘Here’s harmony!’ said Fanny softly. ‘Here’s repose! Here’s what may leave all painting and all music behind, and what poetry only can attempt to describe! Here’s what may tranquillize every care, and lift the heart to rapture! When I look out on such a night as this, I feel as if there could be neither wickedness nor sorrow in the world.’

She spoke with great feeling, and I said it was a great pity that not everyone had been given a taste of nature, for they lost a great deal by it.

‘You taught me to think and feel on the subject,’ she said with a warm smile.

‘I had a very apt scholar,’ I replied. I turned my head to look up at the star-speckled sky. ‘There’s Arcturus looking very bright.’

‘Yes, and the Bear,’ mused Fanny. ‘I wish I could see Cassiopeia. ’

‘We must go out on the lawn for that. Should you be afraid?’

‘Not in the least. It is a great while since we have had any stargazing.’

‘I do not know how it has happened,’ I said.

I was about to give her my arm and suggest we supply our recent lack, when the bustle around the pianoforte died down and the music began.

‘We will stay till this is finished, Fanny,’ I said.

I walked over to the instrument and as I did so Miss Crawford began to sing. I was enchanted by her voice which flowed, silvery, into the warm night; and I was enraptured by the sight of her standing with her hands clasped in front of her, showing the delicacy of her white arms and the grace of her carriage. I was so enchanted by the whole that, when it was over, I asked to hear it again.

The evening at last broke up and I walked Miss Crawford’s party back to the rectory. It was only when I returned to the Park that I realized that Fanny and I had not had our stargazing, after all.

Saturday 27 August

Tom has returned and has regaled us all with stories of Brighton and Weymouth, of parties and friends, and all his doings of the last six weeks. I watched Miss Crawford, fearing to see signs of her earlier liking for him returning but, although she listened politely to everything he had to say, she seemed more interested in talking to me. It relieved me more than I can say. Her face, her voice, her carriage, her air, all delight me. Indeed, I find myself thinking that, if I had anything to offer her, I would be in some danger, for she is the most bewitching woman I have ever met.

Monday 29 August

Henry Crawford has returned to his own estate in Norfolk, for he cannot afford to be absent in September when there is so much to be done. My sisters seem listless without him, for they have both greatly enjoyed his company, but Miss Crawford and Fanny are the same as ever and their spirits carry us through.

Tuesday 30 August

Owen wrote to me this morning inviting me to stay with his family again at Christmas. He suggested I make it a longer visit than previously, as we are going to be ordained together, and I have accepted.

SEPTEMBER

Monday 12 September

After a fortnight’s absence, Henry Crawford is with us once more. He made a welcome addition to our party this evening, for I fear we were all tired of hearing Rushworth’s commentary on his day’s sport, his boasts of his dogs, his jealousies of his neighbours and his zeal after poachers. Indeed, he seems to have no other conversation.

Fanny was surprised at Crawford’s return, for he had told us often that he was fond of change and moving about and she had thought he would have gone on to somewhere gayer than Mansfield. But I was pleased he had come back, for I was sure his presence gave his sister pleasure.

‘What a favorite he is with my cousins!’ Fanny remarked.

I agreed that his manners to women were such as must please and I was heartened to find that Mrs. Grant suspected him of a preference for Julia.

‘I have never seen much symptom of it,’ I confessed to Fanny, ‘but I wish it may be so. He has no faults but what a serious attachment would remove, and I think he would make her a good husband.’

Fanny was silent and looked at the floor. After a minute she said cautiously, ‘If Miss Bertram were not engaged, I could sometimes almost think that he admired her more than Julia.’

‘Which is, perhaps, more in favor of his liking Julia best, than you, Fanny, may be aware,’ I told her kindly, for she has seen very little of the world. ‘I believe it often happens that a man, before he has quite made up his own mind, will distinguish the sister or intimate friend of the woman he is really thinking of more than the woman herself. Crawford has too much sense to stay here if he found himself in any danger from Maria, engaged as she is to Rushworth.’

I found myself wishing Mary Crawford had a friend or unmarried sister here, so that I could distinguish her, for I am afraid of showing Miss Crawford too much attention, and yet I cannot help myself.

I believe I am worrying unnecessarily, though. Even if she suspects a preference on my part, she will not want an offer from a man in my position, and so I need have no fear of raising expectations which I am not in a position to fulfill.

Wednesday 21 September

One of Tom’s friends arrived today. Tom was surprised to see him, for he had issued no more than a casual invitation, but nevertheless he made Yates welcome. Yates’s unexpected arrival was soon explained. He had come from Cornwall where he had been at a house party, but it had been cut short by the sudden death of a relative of those with whom he was staying. He had had no choice but to leave, and remembering Tom’s invitation, he had come to us. He arrived with an air of one whose enjoyment had been curtailed, and on learning we had a violin player in the servants’ hall, he suggested a ball.

Julia and Maria agreed eagerly, whilst Miss Crawford turned a dazzling countenance on him and told him it was an excellent idea. I was in favor of it, too. Fanny had never been to a ball, and I was pleased that her first experience of such an entertainment would take place at Mansfield, where her shyness would be no handicap and where she would be sure of partners. I secured her hand for the first two dances and made sure Tom would ask her later on. I knew I could rely on Crawford to act the gentleman and ask her as well, and so he did. Miss Crawford and I danced together, and though we danced ’till late, I would have been happy for the ball to have gone on ’til dawn.

Thursday 22 September

‘By Jove! we are a happy party,’ said Yates at breakfast. ‘Even happier than the party in Cornwal, or at least happier than we were before Ravenshaw suggested we all perform a play. Ecclesford is one of the best houses in England for doing such a thing. What a time we had of it!

The rehearsals were going along splendidly...’ he said, with a sigh and a shake of the head.

‘It was a hard case, upon my word,’ said Tom.

‘I do think you are very much to be pitied,’ said Maria.

‘The play we were to have performed was Lovers’ Vows, and I was to have been Count Cassel. A trifling part, and not at all to my taste, and such a one as I certainly would not accept again; but I was determined to make no difficulties. Lord Ravenshaw and the duke had appropriated the only two characters worth playing before I reached Ecclesford; and though Lord Ravenshaw offered to resign his to me, it was impossible to take it, you know. Our Agatha was inimitable, and the duke was thought very great by many. And upon the whole, it would certainly have gone off wonderfully. It is not worth complaining about; but to be sure the poor old dowager could not have died at a worse time; and it is impossible to help wishing that the news could have been suppressed for just the three days we wanted. It was but three days; and being only a grandmother, and all happening two hundred miles off, I think there would have been no great harm, and it was suggested, I know; but Lord Ravenshaw, who I suppose is one of the most correct men in England, would not hear of it.’

‘An afterpiece instead of a comedy,’ said Tom. ‘Lovers’ Vows were at an end, and Lord and Lady Ravenshaw left to act My Grandmother by themselves. To make you amends, Yates, I think we must raise a little theatre at Mansfield, and ask you to be our manager.’

The idea seized the party.

‘Let us be doing something,’ said Crawford. ‘Be it only half a play, an act, a scene; what should prevent us? And for a theatre, what signifies a theatre? We shall be only amusing ourselves. Any room in this house might suffice.’

‘We must have a curtain,’ said Tom. ‘A few yards of green baize for a curtain, and perhaps that may be enough.’

‘Oh, quite enough,’ cried Yates, ‘with only just a side wing or two run up, doors in flat, and three or four scenes to be let down; nothing more would be necessary on such a plan as this. For mere amusement among ourselves we should want nothing more.’

I was startled, for such an undertaking would involve a great deal of expense at a time when the estate could little afford it, besides taking the carpenter from his regular duties at a time when he could not be spared. But Tom waved my doubts aside and was soon pressing the merits of a comedy, whilst my sisters and Crawford preferred a tragedy.

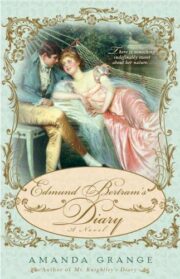

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.