‘Smith has not much above a hundred acres altogether in his grounds, which is little enough, and makes it more surprising that the place can have been so improved. Now, at Sotherton we have a good seven hundred, without reckoning the water meadows; so that I think, if so much could be done at Compton, we need not despair.’

I saw Miss Crawford glance at Maria, and Maria looked pleased at this talk of her future home.

‘There have been two or three fine old trees cut down, that grew too near the house,’ went on Rushworth, ‘and it opens the prospect amazingly, which makes me think that Repton, or anybody of that sort, would certainly have the avenue at Sotherton down: the avenue that leads from the west front to the top of the hill, you know,’ he said. Fanny and I exchanged startled glances.

‘Cut down an avenue!’ said Fanny to me in an aside. ‘What a pity! Does it not make you think of Cowper? Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited.’

‘I am afraid the avenue stands a bad chance, Fanny,’ I said.

The conversation turned to talk of alterations in general and Miss Crawford began to speak of her uncle’s cottage at Twickenham, but as she did so I was surprised to find that she seemed to blame him for the dirt and inconvenience of the alterations he was making. Her liveliness seemed out of place and her droll comments, instead of lifting my spirits, dampened them, for it was disagreeable to hear her speak so slightingly of the man who had taken her in when her parents had died.

I was glad when the conversation moved on to her harp.

‘I am assured that it is safe at Northampton; and there it has probably been these ten days, in spite of the solemn assurances we have so often received to the contrary,’ she said. ‘I am to have it tomorrow; but how do you think it is to be conveyed? Not by a wagon or cart: oh no! nothing of that kind could be hired in the village. I might as well have asked for porters and a handbarrow.’

I smiled at her naïveté, for she was surprised that it should be difficult to hire a horse and cart at this time of year! What did she expect, when the grass had to be got in?

‘I shall understand all your ways in time; but, coming down with the true London maxim, that everything is to be got with money, I was a little embarrassed at first by the sturdy independence of your country customs,’ she said. ‘However, I am to have my harp fetched tomorrow. Henry, who is good-nature itself, has offered to fetch it in his barouche. will it not be honorably conveyed?’

Her humor was infectious, and I found myself looking forward to the morrow, for if there is one instrument I like above all others, it is the harp. Fanny expressed a wish to hear it, too.

‘I shall be most happy to play to you both,’ said Miss Crawford. ‘Now, Mr. Bertram, if you write to your brother, I entreat you to tell him that my harp is come. And you may say, if you please, that I shall prepare my most plaintive airs against his return, in compassion to his feelings, as I know his horse will lose.’

‘If I write, I will say whatever you wish me,’ I replied, rather more reluctantly than I had intended, for I was dismayed to know that she still thought of Tom, even though he was no longer with us.

‘But I do not, at present, foresee any occasion for writing.’

‘What strange creatures brothers are! You would not write to each other but upon the most urgent necessity in the world. Henry, who is in every other respect exactly what a brother should be, who loves me, consults me, confides in me, and will talk to me by the hour together, has never yet turned the page in a letter; and very often it is nothing more than, “Dear Mary, I am just arrived. Bath seems full, and everything as usual. Yours sincerely.” That is the true manly style; that is a complete brother’s letter,’ she said comically. Fanny, however, saw nothing amusing in it, and was indignant on behalf of her own brother, her much-loved William. She could not help saying boldly, ‘When they are at a distance from all their family, they can write long letters.’

I was glad that love had driven her to do what encouragement had not; for it did me good to hear her join in the conversation and express her views, rather than sit quietly by.

‘Miss Price has a brother at sea, whose excellence as a correspondent makes her think you too severe upon us,’ I explained, as Miss Crawford looked startled.

‘Ah. I understand. He is at sea, is he? In the King’s service, of course?’

Fanny had by that time blushed for her own forwardness, but as it was an excellent opportunity for her to speak, I remained resolutely silent, so that she had to continue. As she began to talk of William she lost her shyness, and her voice became animated as she spoke of the foreign stations he had been on; but such was her tenderness that she could not mention the number of years he had been absent without tears in her eyes.

Miss Crawford civilly wished him an early promotion, and a thought occurred to me.

‘Do you know anything of my cousin’s captain? Captain Marshal? You have a large acquaintance in the Navy, I conclude? ’ I asked her, thinking that perhaps something might be done to help William.

‘Among admirals, large enough, for my uncle, as you know, is Admiral Crawford; but we know very little of the inferior ranks,’ she said. ‘Of various admirals I could tell you a great deal: of them and their flags, and the gradation of their pay, and their bickerings and jealousies. But, in general, I can assure you that they are all passed over, and all very ill used.’

Again I was surprised and unsettled by her lack of respect for her uncle and his friends, and I replied with something or nothing, saying, ‘It is a noble profession,’ and the subject soon dropped.

A happier one ensued, and before long we were talking of the improvements to Sotherton again. Crawford’s opinion was sought, as he has done much to improve his own estate, and the long and the short of it is that we are all to make a trip to Sotherton, so that we can give our opinions as to what should be done with the park.

Friday 22 July

I found that Miss Crawford’s remarks about her uncle preyed on my mind and I decided to consult Fanny, for I knew I could rely on her judgment. I repaired to her sitting-room at the top of the house and tapped on the door. A gentle ‘Come in’ bid me enter, and I was soon inside the room. I felt better the moment I stepped over the threshold. Everything about the room spoke of Fanny’s personality: the three transparencies glowing in the window, showing the unlikely juxtaposition of Tintern Abbey, a cave in Italy and a moonlight lake in Cumberland; the family profiles hanging over the mantelpiece; the geraniums and the books; the writing desk; the works of charity; and the sketch of HMS Antwerp, done for her by William, pinned against the wall. I believe there is scarcely a room in the house with so much character or so much warmth.

‘Well, Fanny, and how do you like Miss Crawford now?’ I asked her as I took a seat.

‘Very well,’ she said with a smile. ‘Very much. I like to hear her talk. She entertains me; and she is so extremely pretty, that I have great pleasure in looking at her.’

‘She has a wonderful play of feature!’ I agreed, lost, for the moment, in remembrance of her beauty. But then I returned to my reason for coming. ‘Was there nothing in her conversation that struck you, Fanny, as not quite right?’

‘Oh yes!’ she said at once, as though reading my mind. ‘She ought not to have spoken of her uncle as she did.’

I knew she would see it and I let out a sigh as I was reassured that I had not been wrong. But when Fanny went on to speak of Miss Crawford as ungrateful I had to defend her, saying,

‘Ungrateful is a strong word. She is awkwardly circumstanced. With such warm feelings and lively spirits it must be difficult to do justice to her affection for her departed aunt, without throwing a shade on the admiral.’

‘Do not you think,’ said Fanny, after a little consideration, ‘that this impropriety is a reflection upon that aunt, as her niece has been entirely brought up by her?’

At this, I was struck anew by Fanny’s intelligence, for that was undoubtedly the case: Miss Crawford’s faults were not her own, they were the faults of her upbringing.

‘Her present home must do her good,’ I said, much relieved. ‘Mrs. Grant’s manners are just what they ought to be. I am glad you saw it all as I did, Fanny. No doubt, before long, Miss Crawford will see it all as we do, too.’

Having eased my feelings, I spent the afternoon seeing to estate business, but I could not keep my mind on my work, for it kept drifting back to Mary Crawford. She is the kind of woman I most admire, with a slight figure, dainty and elegant, and just the sort of features I love to look at. She has sense and cleverness and quickness of spirits. She is in every way an addition to Mansfield Park.

Saturday 23 July

The harp has arrived, and after dinner at the rectory, Miss Crawford took her place at the instrument. Beyond her was the window, cut down to the ground, and through it I could see the little lawn surrounded by shrubs. Clad in the rich foliage of summer the garden made a striking contrast with her white silk gown and set her off to great advantage. I was surprised at Crawford, who whispered to my sister Maria throughout the recital, for the music was excellent, and I could scarce take my eyes away from Miss Crawford as she played.

‘You are an avid listener, Mr. Bertram,’ she said, as she stood up at last. ‘I do not believe I have ever had a more attentive audience.’

I thought fleetingly of Tom’s ease with women and the kind of clever reply he would have made, but I was not adept at teasing phrases and I could only assure her of my great pleasure in listening to her. It seemed to satisfy her, however, for she smiled at me, and I felt myself drawn to her even more.

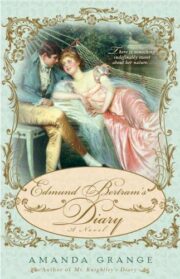

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.