Although the dinner was informal, the party naturally moved together to enter the dining room in pairs. The colonel at once offered his arm to Elizabeth, Darcy moved to Jane’s side and Bingley, with a little show of gallantry, offered his arm to Georgiana. Seeing Alveston walking alone behind the last pair, Elizabeth wished she had arranged things better, but it was always difficult to find a suitable unescorted lady at short notice and convention had not before mattered at these pre-ball dinners. The empty chair was between Georgiana and Bingley, and when Alveston took it, Elizabeth detected his transitory smile of pleasure.

As they seated themselves the colonel said, “So Mrs Hopkins is not with us again this year. Isn’t this the second time she has missed the ball? Does your sister not enjoy dancing, or has the Reverend Theodore theological objections to a ball?”

Elizabeth said, “Mary has never been fond of dancing and has asked to be excused, but her husband has certainly no objection to her taking part. He told me on the last occasion when they dined here that in his view no ball at Pemberley attended by friends and acquaintances of the family could have a deleterious effect on either morals or manners.”

Bingley whispered to Georgiana, “Which shows that he has never imbibed Pemberley white soup.”

The remark was overheard and provoked smiles and some laughter. But this light-heartedness was not to last. There was an absence of the usual eager talk across the table, and a languor from which even Bingley’s good-humoured volubility seemed unable to rouse them. Elizabeth tried not to glance too frequently at the colonel, but when she did she was aware how often his eyes were fixed on the couple opposite. It seemed to Elizabeth that Georgiana, in her simple dress of white muslin with a chaplet of pearls in her dark hair, had never appeared more lovely, but there was in the colonel’s gaze a look more speculative than admiring. Certainly the young couple behaved impeccably, Alveston showing Georgiana no more attention than was natural, and Georgiana turning to address her remarks equally between Alveston and Bingley, like a young girl dutifully following social convention at her first dinner party. There was one moment, which she hoped the colonel had not detected. Alveston was mixing Georgiana’s water and wine and, for a few seconds, their hands touched and Elizabeth saw the faint flush grow and fade on Georgiana’s cheeks.

Seeing Alveston in his formal evening clothes, Elizabeth was struck again by his extraordinary good looks. He was surely not unaware that he could not enter a room without every woman present turning her eyes towards him. His strong mid-brown hair was tied back simply at the nape of his neck. His eyes were a darker brown under straight brows, his face had an openness and strength which saved him from any imputation of being too handsome, and he moved with a confident and easy grace. As she knew, he was usually a lively and entertaining guest, but tonight even he seemed afflicted by the general air of unease. Perhaps, she thought, everyone was tired. Bingley and Jane had come only eighteen miles but had been delayed by the high wind, and for Darcy and herself the day before the ball was always unusually busy.

The atmosphere was not helped by the tempest outside. From time to time the wind howled in the chimney, the fire hissed and spluttered like a living thing and occasionally a burning log would break free, bursting into spectacular flames and casting a momentary red flush over the faces of the diners so that they looked as if they were in a fever. The servants came and went on silent feet, but it was a relief to Elizabeth when the meal at last came to an end and she was able to catch Jane’s eye and move with her and Georgiana across the hall into the music room.

4

While the dinner was being served in the small dining room, Thomas Bidwell was in the butler’s pantry cleaning the silver. This had been his job for the last four years since the pain in his back and knees had made driving impossible, and it was one in which he took pride, particularly on the night before Lady Anne’s ball. Of the seven large candelabra which would be ranged the length of the supper table, five had already been cleaned and the last two would be finished tonight. The job was tedious, time-consuming and surprisingly tiring, and his back, arms and hands would all ache by the time he had finished. But it wasn’t a job for the maids or for the lads. Stoughton, the butler, was ultimately responsible, but he was busy choosing the wines and overseeing the preparation of the ballroom, and regarded it as his responsibility to inspect the silver once cleaned, not to clean even the most valuable pieces himself. For the week preceding the ball it was expected that Bidwell would spend most days, and often far into the night, seated aproned at the pantry table with the Darcy family silver ranged before him – knives, forks, spoons, the candelabra, silver plates on which the food would be served, the dishes for the fruit. Even as he polished he could picture the candelabra with their tall candles throwing light on bejewelled hair, heated faces and the trembling blossoms in the flower vases.

He never worried about leaving his family alone in the woodland cottage, nor were they ever frightened there. It had lain desolate and neglected for years until Darcy’s father had restored it and made it suitable for use by one of the staff. But although it was larger than a servant could expect and offered peace and privacy, few were prepared to live there. It had been built by Mr Darcy’s great-grandfather, a recluse who lived his life mostly alone, accompanied only by his dog, Soldier. In that cottage he had even cooked his own simple meals, read and sat contemplating the strong trunks and tangled bushes of the wood which were his bulwark against the world. Then, when George Darcy was sixty, Soldier became ill, helpless and in pain. It was Bidwell’s grandfather, then a boy helping with the horses, who had gone to the cottage with fresh milk and found his master dead. Darcy had shot both Soldier and himself.

Bidwell’s parents had lived in the cottage before him. They had been unworried by its history, and so was he. The reputation that the woodland was haunted arose from a more recent tragedy which occurred soon after the present Mr Darcy’s grandfather succeeded to the estate. A young man, an only son who worked as an under-gardener at Pemberley, had been found guilty of poaching deer on the estate of a local magistrate, Sir Selwyn Hardcastle. Poaching was not usually a capital offence and most magistrates dealt with it sympathetically when times were hard and there was much hunger, but stealing from a deer park was punishable by death and Sir Selwyn’s father had been adamant that the full penalty should be exacted. Mr Darcy had made a strong plea for leniency in which Sir Selwyn refused to join. Within a week of the boy’s execution his mother had hanged herself. Mr Darcy had at least done his best, but it was believed that the dead woman had held him chiefly responsible. She had cursed the Darcy family, and the superstition took hold that her ghost, wailing in grief, could be glimpsed wandering among the trees by those unwise enough to visit the woodland after dark, and that this avenging apparition always presaged a death on the estate.

Bidwell had no patience with this foolishness but the previous week the news had reached him that two of the housemaids, Betsy and Joan, had been whispering in the servants’ hall that they had seen the ghost when venturing into the woodland as a dare. He had warned them against speaking such nonsense which, had it reached the ears of Mrs Reynolds, might have had serious consequences for the girls. Although his daughter, Louisa, no longer worked at Pemberley, being needed at home to help nurse her sick brother, he wondered if somehow the story had reached her ears. Certainly she and her mother had become more meticulous than ever about locking the cottage door at night and, when returning late from Pemberley, he had been instructed to give a signal by knocking three times loudly and four times more quietly before inserting his key.

The cottage was reputed to be unlucky but only in recent years had ill luck touched the Bidwells. He still remembered, as keenly as if it were yesterday, the desolation of that moment when, for the last time, he had taken off the impressive livery of Mr Darcy of Pemberley’s head coachman and said goodbye to his beloved horses. And now for the past year his only son, his hopes for the future, had been slowly and painfully dying.

If that were not enough, his elder daughter, the child from whom he and his wife had never expected trouble, was causing anxiety. Things had always gone well with Sarah. She had married the son of the innkeeper at the King’s Arms in Lambton, an ambitious young man who had moved to Birmingham and established a chandlery with a bequest from his grandfather. The business was flourishing, but Sarah had become depressed and overworked. There was a fourth baby due in just over four years of marriage and the strain of motherhood and helping in the shop had brought a despairing letter asking for help from her sister Louisa. His wife had handed him Sarah’s letter without comment but he knew that she shared his concern that their sensible, cheerful, buxom Sarah had come to such a pass. He had handed the letter back after reading it, merely saying, “Louisa will be sadly missed by Will. They’ve always been close. And can you spare her?”

“I’ll have to. Sarah wouldn’t have written if she wasn’t desperate. It’s not like our Sarah.”

So Louisa had spent the five months before the birth in Birmingham helping to care for the other three children and had remained for a further three months while Sarah recovered. She had recently returned home, bringing the baby, Georgie, with her, both to relieve her sister and so that her mother and brother could see him before Will died. But Bidwell himself had never been happy about the arrangement. He had been almost as anxious as his wife to see their new grandson, but a cottage where a dying man was being nursed was hardly suitable for the care of a baby. Will was too ill to take much more than a cursory interest in the new arrival and the child’s crying at night worried and disturbed him. And Bidwell could see that Louisa was not happy. She was restless and, despite the autumnal chill, she seemed to prefer walking in the woodland, the baby in her arms, than to be at home with her mother and Will. She had even, as if by design, been absent when the rector, the elderly and scholarly Reverend Percival Oliphant, made one of his frequent visits to Will, which was strange because she had always liked the rector, who had taken an interest in her from her childhood, lending her books and offering to include her in his Latin class with his small group of private pupils. Bidwell had refused the invitation – it would only give Louisa ideas above her station – but still, it had been made. Of course, a girl was often anxious and nervous as her wedding approached, but now that Louisa was at home why did not Joseph Billings visit the cottage regularly as he used to do? They hardly saw him. He wondered whether the care of the baby had brought home both to Louisa and to Joseph the responsibilities and risks of the married state and caused them to reconsider. He hoped not. Joseph was ambitious and serious, and some thought, at thirty-four, too old for Louisa, but the girl seemed fond of him. They would be settled in Highmarten within seventeen miles of himself and Martha and would be part of a comfortable household with an indulgent mistress, a generous master, their future secured, their lives stretching ahead, predictable, safe, respectable. With all that before her, what use to a young woman were learning and Latin?

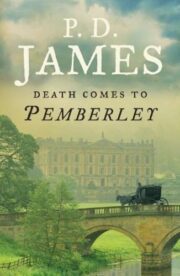

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.