“So, as far as Wickham and I knew, all had been arranged satisfactorily. The child would be accepted and loved by his aunt and uncle and would never know his true parentage, Louisa would make the suitable marriage previously planned, and so the matter rested.

“Wickham is not a man who likes to act alone when an ally or companion can be found, a lack of prudence which probably accounts for his folly in taking Miss Lydia Bennet with him when he escaped from his creditors and obligations in Brighton. Now he confided in his friend Denny, and more fully in Mrs Younge, who seems to have been a controlling presence in his life since his youth. I believe it is regular stipends from her which have largely supported him and Mrs Wickham while he has been unemployed. He asked Mrs Younge to visit the woodland in secret so that she could report on the child’s progress, and this Mrs Younge did, passing herself off as a visitor to the district and meeting Louisa by arrangement as she was carrying the baby in the woodland. The result was, however, in one respect unfortunate; Mrs Younge took an immediate fancy to the boy and was determined that she and not the Simpkinses should adopt him. Then what seemed a disaster turned to her advantage: Michael Simpkins wrote that he was not prepared to bring up another man’s child. Apparently relations had not been good between the sisters during Louisa’s confinement and Mrs Simpkins already had three children and would no doubt have more. The Simpkinses would look after the child for another three weeks to enable Louisa to find a home for him, but no longer. This news was confided by Louisa to Wickham, and by him to Mrs Younge. Louisa was, of course, desperate. She had to find a home for the child and soon Mrs Younge’s offer was seen as a solution to all their problems.

“Wickham had informed Mrs Younge of my interest in this matter and of the thirty pounds I had promised and had, indeed, passed to Wickham. She knew that I was due to be at Pemberley for Lady Anne’s ball since this was my invariable practice when on leave from the army, and Wickham had always made it his business to know what was happening at Pemberley, largely through the reports of his wife who was a frequent visitor to Highmarten. Mrs Younge wrote to me at my London address, saying that she was interested in adopting the child and would be at the King’s Arms for two days, and that she wished to discuss the possibility with me since she understood that I was an interested party. An appointment was made for nine o’clock on the night before Lady Anne’s ball when she assumed that everyone would be too busy to remark on my absence. I have no doubt, Darcy, that you thought it both strange and discourteous of me to leave the music room so peremptorily with the excuse that I wanted a ride. I had no option but to keep the appointment although I had little doubt what the lady had in mind. You will recall that she was both attractive and elegant at our first meeting, and I found her still a beautiful woman although, after eleven years, I would not have recognised her with any certainty.

“She was very persuasive. You must remember, Darcy, that I only saw her once when you and I interviewed her as a prospective companion to Miss Georgiana, and you know how impressive and plausible she could be. She was obviously successful financially and had arrived at the inn with her own coach and coachman accompanied by her maid. She produced statements from her bank proving that she was well able to support the child, but said – almost with a smile – that she was a cautious woman and would expect the thirty pounds to be doubled but thereafter there would be no further payments. If the boy were adopted by her, he would be removed from Pemberley for ever.”

Darcy said, “You were putting yourself in the power of a woman you knew to be corrupt and who was almost certainly a blackmailer. Apart from the money she received from her lodgers, how else did she live in such opulence? You knew from our previous dealings with her what sort of a woman she was.”

The colonel said, “They were your previous dealings, Darcy, not mine. I admit that it was our joint decision that she should take over the care of Miss Darcy, but that was the only previous occasion on which we met. You may have had dealings with her later, but I am not privy to those and have no wish so to be. Listening to her and studying the evidence she brought with her, I was convinced that the solution being offered for Louisa’s baby was both sensible and right. Mrs Younge was obviously fond of the child and willing to make herself responsible for his future maintenance and education; above all he would be totally removed from Pemberley or any association with Pemberley. That was the first consideration to me, and I believe that it would have been to you. I would not have acted against the mother’s wishes for her child, nor have I done so.”

“Would Louisa really have been happy for her child to be given to a blackmailer and a kept woman? Did you really believe that Mrs Younge would not come back to you for more money time and time again?”

The Colonel smiled. “Darcy, I am occasionally surprised at how naive you are, how little you know about the world outside your beloved Pemberley. Human nature is not as black and white as you suppose. Mrs Younge was undoubtedly a blackmailer, but she was a successful one and saw it as a reliable business provided it was run with discretion and sense. It is the unsuccessful blackmailers who end in prison or on the scaffold. She asked what her victims could afford but she never bankrupted them or made them desperate, and she kept to her word. I have no doubt you paid for her silence when you dismissed her from your service. Has she ever spoken of her time when she was in charge of Miss Darcy? And after Wickham and Lydia eloped, and you persuaded her to give you their address, you must have paid heavily for that information, but has she ever spoken of the matter? I am not defending her, I know what she was, but I found her easier to deal with than most of the righteous.”

Darcy said, “I am not so naive, Fitzwilliam, as you suppose. I have long known how she operates. So what happened to Mrs Younge’s letter to you? It would be interesting to see what promises she made to induce you not only to support her plan to adopt the child, but to pay over more money. You yourself can hardly be so naive as to suppose Wickham would return his thirty pounds.”

“I burnt the letter when we spent that night in the library. I waited until you were asleep and then put it in the fire. I could see no further use for it. Even had Mrs Younge’s motives been suspect and she had later broken faith, how could I take legal action against her? It has always been my belief that any letter which contains information which should never be generally known ought to be destroyed; there is no other security. As to the money, I proposed, and with every confidence, to leave it to Mrs Younge to persuade Wickham to part with it. I could be sure that she would succeed; she had experience and inducements which I lacked.”

“And your early rising in the morning when you suggested that we sleep in the library, and your visit to check on Wickham – were they part of your plan?”

“If I had found him awake and sober and had the opportunity, I wanted to impress on him that the circumstances under which he received the thirty pounds must remain totally secret and that he should adhere to this in any court unless I myself revealed the truth when he would be free to confirm my statement. I would say, if questioned by the police or in court, that the reason I gave him the thirty pounds was to enable him to settle a debt of honour, which was indeed true, and that I had given my word that the circumstances of this debt would never be revealed.”

Darcy said, “I doubt that any court would press Colonel the Lord Hartlep to break his word. They might wish to ascertain whether the money was intended for Denny.”

“Then I should be able to reply that it was not. It was important to the defence that this was established at the trial.”

“I have been wondering why, before we set off to find Denny and Wickham, you hurried to see Bidwell and dissuade him from joining us in the chaise and returning to Woodland Cottage. You acted before Mrs Darcy had a chance to issue her instructions to Stoughton or Mrs Reynolds. It struck me at the time that you were being unnecessarily, even presumptuously, helpful; but now I understand why Bidwell had to be kept away from Woodland Cottage that night, and why you went there to warn Louisa.”

“I was presumptuous, and I make a belated apology. It was, of course, vital that the two women were aware that the plan to collect the baby next morning might have to be abandoned. I was tired of the whole subterfuge and felt that it was time for the truth. I told them that Wickham and Captain Denny were lost in the woodland and that Wickham, the father of Louisa’s child, was married to Mr Darcy’s sister.”

Darcy said, “Louisa and her mother must have been left in a state of dreadful distress. It is difficult to imagine the shock to both of them at learning that the child they were nurturing was Wickham’s bastard and that he and a friend were lost in the woodland. They had heard the pistol shots and must have feared the worst.”

“There was nothing I could do to reassure them. There wasn’t time. Mrs Bidwell gasped out, “This will kill Bidwell. Wickham’s son here in Woodland Cottage! The stain on Pemberley, the appalling shock for the master and Mrs Darcy, the disgrace for Louisa, for us all.” It is interesting that she put them in that order. I was worried for Louisa. She almost fainted, then crept to a fireside chair and sat there violently shivering. I knew she was in shock but there was nothing I could do. I had already been absent for longer than you, Darcy, and Alveston could have expected.”

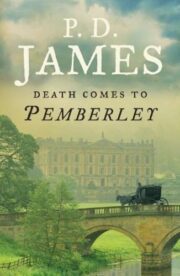

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.