Mr Justice Moberley had made no notes and now he leaned a little towards the jury as if the matter could have no concern to the rest of the court, and the beautiful voice which at first attracted Darcy was clear enough to be heard by everyone present. He went through the evidence succinctly but carefully, as if time had no importance. The speech ended with words that Darcy felt gave credence to the defence, and his spirits rose.

“Gentlemen of the jury, you have listened with patience and obviously close attention to the evidence given in this long trial, and it is now for you to consider the evidence and give your verdict. The accused was previously a professional soldier and has a record of conspicuous gallantry for which he has been awarded a medal, but this should not affect your decision, which should be based on the evidence which has been presented to you. Your responsibility is a heavy one but I know you will discharge your duty without fear or favour and in accordance with the law.

“The central mystery, if I can call it that, surrounding this case is why Captain Denny ran into the woodland when he could have safely and comfortably remained in the chaise; it is inconceivable that an attack would have been made on him in the presence of Mrs Wickham. The accused has given his explanation of why Captain Denny so unexpectedly stopped the chaise, and you will wonder whether you find this explanation satisfactory. Captain Denny is not alive to explain his action, and no evidence other than Mr Wickham’s is available to elucidate the matter. Like much of this case, it has been supposition, and it is on sworn evidence, not on unsubstantiated opinions, that your verdict can safely be given: the circumstances under which members of the rescue party found Captain Denny’s body and heard the words attributed to the accused. You have heard his explanation of their meaning and it is for you to decide whether or not you believe him. If you are certain beyond reasonable doubt that George Wickham is guilty of killing Captain Denny then your verdict will be one of guilty; if you have not that certainty the accused is entitled to be acquitted. I now leave you to your deliberations. If it is your wish to retire to consider your verdict, a room has been made available.”

10

By the end of the trial Darcy felt as drained as if he himself had stood in the dock. He longed to ask Alveston for reassurance but pride and the knowledge that to badger him would be as irritating as it was futile kept him silent. There was nothing anyone could do now but hope and wait. The jury had chosen to retire to consider their verdict and in their absence the courtroom had again become as noisy as an immense parrots’ cage as the audience discussed the evidence and made bets on the verdict. They had not long to wait After less than ten minutes the jury returned. He heard the loud authoritative voice of the clerk asking the jury, “Who is your foreman?”

“I am, sir.” The tall dark man who had gazed at him so frequently during the trial and who was their obvious leader stood up.

“Have you arrived at a verdict?”

“We have.”

“Do you find the prisoner guilty or not guilty?”

The answer came without hesitation. “Guilty.”

“And is that the verdict of you all?”

“It is.”

Darcy knew that he must have gasped. He felt Alveston’s hand on his arm, steadying him. And now the court was full of voices – a mixture of groans, cries and protests which grew until, as if by some group compulsion, the noise died and all eyes were turned on Wickham. Darcy, caught up in the outcry, closed his eyes, then forced himself to open them and fixed them on the dock. Wickham’s face had the stiffness and sickly pallor of a mask of death. He opened his mouth as if to speak, but no words came. He was clutching the edge of the dock and seemed for a moment to stagger, and Darcy felt his own muscles tightening as he watched while Wickham recovered himself and with obvious effort found the strength to stand stiffly upright. Staring at the judge he found a voice, at first cracked, but then loud and clear. “I am innocent of this charge, my lord. I swear before God I am not guilty.” Wide-eyed, he gazed desperately round the courtroom as if seeking some friendly face, some voice which would affirm his innocence. Then he said again with more force, “I am not guilty, my lord, not guilty.”

Darcy turned his eyes to where Mrs Younge had been sitting, soberly dressed and silent among the silks and muslins and the fluttering fans. She had gone. She must have moved as soon as the verdict was delivered. He knew that he had to find her, needed to know what part she had played in the tragedy of Denny’s death, to find out why she had been there, her eyes locked on Wickham’s as if some power, some courage were passing between them.

He broke free of Alveston and pushed his way to the door. It was being firmly held fast against a crowd outside who, from the increasing clamour, were apparently determined on admission. And now the bawling in the courtroom was rising again, becoming less pitiable and more angry. He thought he heard the judge threatening to call the police or army to expel the troublemakers, and someone close to him was saying, “Where is the black cap? Why in God’s name cannot they lay their hand on the damn thing and put it on his head?” There was a shout as if in triumph and, glancing round, he saw a black square being flourished above the crowd by a young man hoisted on his comrade’s shoulders and knew with a shudder that this was the black cap.

He fought his way to keep his place at the door and, as the crowd outside edged it open, managed to struggle through and elbowed his way to the road. Here too there was a commotion, the same cacophony of groans, cries and a chorus of shouting voices, more, he thought, in pity than in anger. A heavy coach had been drawn up, the crowd attempting to pull the driver down from his seat. He was shouting, “It weren’t my fault. You saw the lady. She flung herself right under the wheels!”

And there she lay, squashed under the heavy wheels as if she were a stray animal, her blood flowing in a red stream to pool under the horses’ feet. Smelling it, they neighed and reared and the coachman had difficulty in controlling them. Darcy took one look and, turning away, vomited violently into the gutter. The sour stink seemed to poison the air. He heard a voice cry, “Where’s the death van? Why don’t they take her away? It’s not decent leaving her there.”

The passenger in the coach made to get out but, seeing the sight of the crowd, shrank back inside and pulled down the blind, obviously waiting for the constables to arrive and restore order. The crowd seemed to grow, among them children gazing incomprehensibly and women with babes in arms who, frightened by the noise, began wailing. There was nothing he could do. He needed now to return to the courtroom and find the colonel and Alveston in the hope that they might offer reassurance; in his heart he knew that there could be none.

And then he saw the hat trimmed with purple and green ribbons. It must have fallen from her head and bowled along the pavement and had now stopped at his feet. He gazed at it as if in a trance. Nearby a staggering woman, yelling baby under one arm, gin bottle in her hand, pushed forward, stooped and clasped it crookedly on her head. Grinning at Darcy, she said, “No use to her any more, is it?” and was gone.

11

The competing attraction of a dead body had diverted some of the men by the door and he was able to fight his way to the front and was borne in with the last six to gain admission. Someone called in a stentorian voice, “A confession! They have brought a confession!” and immediately the court was in an uproar. It seemed for a moment that Wickham would be dragged from the dock, but he was immediately surrounded by officers of the court and, after standing upright for a few dazed moments, sat down with his hands over his face. The noise increased. And it was then that he saw Dr McFee and the Reverend Percival Oliphant surrounded by police constables. Amazed by their presence, he watched while two heavy chairs were being dragged forward and they both slumped into them as if exhausted. He tried to push his way through to them but the dense crowd was a heaving impenetrable mass.

People had left their seats and were now approaching the judge. He raised his gavel and used it vigorously, and at last was able to make his voice heard and the clamour died. “Officer, lock the doors. If there is any more disturbance I shall order the court to be cleared. The document which I have perused purports to be a signed confession witnessed by you two gentlemen, Dr Andrew McFee and the Reverend Percival Oliphant. Gentlemen, are these your signatures?”

Dr McFee and Mr Oliphant spoke together. “They are, my lord.”

“And is this document you have handed in the handwriting of the person who has signed it above your signatures?”

Dr McFee answered. “Part of it is, my lord. William Bidwell was at the end of his life and wrote his confession propped up in bed but I trust the writing, although shaky, is sufficiently clear to read. The last paragraph, as indicated by the change of handwriting, was written by me to dictation by William Bidwell. He was then able to speak but not to write, except to sign his name.”

“Then I shall ask counsel for the defence to read it. Afterwards I shall consider how best to proceed. If anyone interrupts he will be made to leave.”

Jeremiah Mickledore took the document and, adjusting his spectacles, scanned it and then began to read in a loud and clear voice. The whole courtroom was silent.

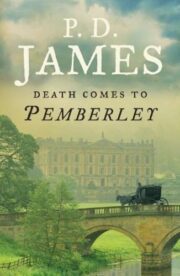

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.