Since Hardcastle had strongly advised that it would be unwise for Darcy to meet Wickham before the inquest had been held, Bingley, with his usual good nature, volunteered for the task and he had visited on Monday morning, when the prisoner’s immediate necessities had been dealt with and enough money passed to ensure that he could purchase the food and other comforts which could help make imprisonment bearable. But, after further thought, Darcy had decided that he had a duty to visit Wickham, at least once before the inquest. Not to do so would be taken throughout Lambton and Pemberley village to be a clear sign that he believed his brother-in-law to be guilty, and it was from the Lambton and Pemberley parishes that the inquest jury would be drawn. He might have no choice about being called as a witness for the prosecution, but at least he could demonstrate quietly that he believed Wickham to be innocent. There was, too, a more private concern: he was deeply concerned that there should be no open conjecture about the reason for the family estrangement which might put the matter of Georgiana’s proposed elopement at risk of discovery. It was both just and expected that he should go to the prison.

Bingley had reported that he had found Wickham sullen, uncooperative and prone to burst out in incivilities against the magistrate and the police, demanding that their efforts be redoubled to discover who had murdered his chief – indeed his only – friend. Why did he languish in gaol while the guilty went unsought? Why did the police keep interrupting his rest to harass him with stupid and unnecessary questions? Why had they asked why he had turned Denny over? To see his face, of course, it was a perfectly natural action. No, he had not noticed the wound on Denny’s head, it was probably covered by his hair and, anyway, he was too distressed to notice details. And what, he was asked, had he been doing in the time between the shots being heard and the finding of Denny’s body by the search party? He was stumbling through the woodland trying to catch a murderer, and that was what they should be doing, not wasting time pestering an innocent man.

Today Darcy found a very different man. Now, in fresh clothes, shaved and his hair combed, Wickham received him as if in his own home, bestowing a favour on a not particularly welcome visitor. Darcy remembered that he had always been a creature of moods and now he recognised the old Wickham, handsome, confident and more inclined to relish his notoriety than to see it as a disgrace. Bingley had brought the articles for which he had asked: tobacco, several shirts and cravats, slippers, savoury pies baked at Highmarten to augment the food purchased for him from the local bakery, and ink and paper with which Wickham proposed to write an account both of his part in the Irish campaign and of the deep injustice of his present imprisonment, a personal record which he was confident would find a ready market. Neither man spoke of the past. Darcy could not rid himself of its power but Wickham lived for the moment, was sanguine about the future and reinvented the past to suit his audience, and Darcy could almost believe that, for the present, he had put the worst of it completely out of his mind.

Wickham said that the Bingleys had brought Lydia from Highmarten to visit him the previous evening but she had been so uncontrolled in her complaints and weeping that he had found the occasion too dispiriting to be tolerated and had instructed that in future she should be admitted only at his request and for fifteen minutes. He was hopeful, however, that no further visit would be necessary; the inquest had been fixed for Wednesday at eleven o’clock and he was confident that he would then be released, after which he envisaged the triumphant return of Lydia and himself to Longbourn and the congratulations of his former friends at Meryton. No mention was made of Pemberley, perhaps because even in his euphoria he hardly expected to be welcomed there, nor wished to be. No doubt, thought Darcy, in the happy event of his release, he would first join Lydia at Highmarten before travelling on to Hertfordshire. It seemed unjust that Jane and Bingley should be burdened with Lydia’s presence even for a further day, but all that could be decided if his release indeed took place. He wished he could share Wickham’s confidence.

He stayed only for half an hour, was provided with a list of requirements to be brought the next day, and left with Wickham’s request that his compliments should be paid to Mrs Darcy and to Miss Darcy. Leaving, he reflected that it was a relief to find Wickham no longer sunk in pessimism and incrimination, but the visit had been uncomfortable for him and singularly depressing.

He knew, and with bitterness, that if the trial went well he would have to support Wickham and Lydia, at least for the foreseeable future. Their spending had always exceeded their income, and he guessed that they had depended on private subventions from Elizabeth and Jane to augment an inadequate income. Jane occasionally still invited Lydia to Highmarten while Wickham, loudly complaining in private, amused himself by staying in a variety of local inns, and it was from Jane that Elizabeth had news of the couple. None of the temporary jobs Wickham had taken since resigning his commission had been a success. His latest attempt to earn a competence had been with Sir Walter Elliot, a baronet who had been forced by extravagance to rent his house to strangers and had moved to Bath with two of his daughters. The younger, Anne, had since made a prosperous and happy marriage with a naval captain, now a distinguished admiral, but the elder, Elizabeth, had still to find a husband. The baronet, disenchanted with Bath, had decided that he was now sufficiently prosperous to return home, gave his tenant notice and had employed Wickham as a secretary to assist with the necessary work occasioned by the move. Wickham had been dismissed within six months. When faced with depressing news of public discord or, worse, of family disagreements it was always Jane’s reconciling task to find no party greatly at fault. But when the facts of Wickham’s latest failure were passed on to her more sceptical sister, Elizabeth suspected that Miss Elliot had been worried by her father’s response to Lydia’s open flirtation, while Wickham’s attempt to ingratiate himself with her had been met, at first with some encouragement born of boredom and vanity, finally with disgust.

Once away from Lambton, it was good to take deep breaths of cool fresh-smelling air, to be free of the unmistakable prison smell of bodies, food and cheap soap and the clank of turning keys, and it was with a surge of relief and a sense that he himself had escaped from durance that Darcy turned his horse’s head towards Pemberley.

5

Pemberley was as quiet as if it were uninhabited, and it was apparent that Elizabeth and Georgiana had not yet returned. He had hardly dismounted when one of the stable boys came round the corner of the house to take his horse, but he must have returned earlier than expected and there was no one waiting at the door. He entered the silent hall and made for the library where he thought it likely that he would find the colonel impatient for news. But to his surprise he discovered Mr Bennet there alone, ensconced in a high-backed chair by the fire, reading the Edinburgh Review. It was clear from the empty cup and soiled plate on a small table at his side that he had been provided with refreshment after his journey. After a second’s pause, occasioned by surprise, Darcy realised that he was exceedingly glad to see this unexpected visitor, and as Mr Bennet rose from his chair, shook hands with him warmly.

“Please don’t disturb yourself, sir. It is a great pleasure to see you. I hope you have been attended?”

“As you see. Stoughton has been his usual efficient self and I have met Colonel Fitzwilliam. After greeting me he said he would take advantage of my arrival to exercise his horse; I had the impression that he was finding confinement to the house a little tedious. I have also been welcomed by the estimable Mrs Reynolds who assures me that my usual room is always kept ready.”

“When did you arrive, sir?”

“About forty minutes ago. I hired a chaise. That is not the most comfortable way to travel far and I had it in mind to come by coach. Mrs Bennet, however, complained that she needs it to convey the most recent news of Wickham’s unfortunate situation to Mrs Philips, the Lucases and the many other interested parties in Meryton. To use a hack-chaise would be demeaning, not only to her but to the whole family. Having proposed to abandon her at this distressing time I could not deprive her of a more valued comfort; Mrs Bennet has the coach. I have no wish to cause additional work by this unannounced arrival but I thought you might be glad to have another man in the house when you were concerned with the police or with Wickham’s comfort. Elizabeth told me in her letter that the colonel is likely to be recalled soon to his military duties and young Alveston to London.”

Darcy said, “They will depart after the inquest, which I heard on Sunday will be held tomorrow. Your presence here, sir, will be a comfort to the ladies and a reassurance to me. Colonel Fitzwilliam will have acquainted you with the facts of Wickham’s arrest.”

“Succinctly, but no doubt accurately. He could have been giving me a military report. I almost felt obliged to throw a salute. I think that throwing a salute is the correct expression, I have no experience of military matters. Lydia’s husband seems to have distinguished himself by this latest exploit in managing to combine entertainment for the masses with the maximum embarrassment for his family. The colonel told me you were at Lambton visiting the prisoner. How did you find him?”

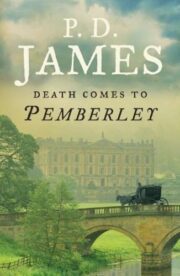

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.