Hardcastle said with a degree of self-satisfaction, “That will hardly be necessary, Lord Hartlep. It was convenient for me to call at the King’s Arms on the way here this morning to check whether there had been any strangers staying there on Friday, and I was told about the lady. Your friend made quite an impression at the inn; a very pretty coach, so they told me, and her own maid and a manservant. I imagine that she spent lavishly and the innkeeper was sorry to see her go.”

It was then time for Hardcastle to interview the staff, assembled as before in the servants’ hall, the only one absent being Mrs Donovan who had no intention of leaving the nursery unprotected. Since guilt is more commonly felt by the innocent than by the culpable, the atmosphere was less of expectation than of anxiety. Hardcastle had resolved to make his discourse as reassuring and as brief as possible, an intention which was partly vitiated by his customary stern warnings of the terrible consequences for people who refused to co-operate with the police or who withheld information. In a gentler voice he continued, “I have no doubt that all of you on the night before Lady Anne’s ball had better things to do than make your way through the stormy night with the purpose of murdering a complete stranger in the wild woodland. I will now ask any of you who have information to give, or if you left Pemberley at any time last night between the hours of seven o’clock and seven o’clock this morning, to hold up your hands.”

Only one hand was held up. Mrs Reynolds whispered, “Betsy Collard, sir, one of the housemaids.”

Hardcastle demanded that she stand up, which Betsy immediately did, and without apparent reluctance. She was a stout, confident girl and spoke clearly, “I was with Joan Miller, sir, in the woodland last Wednesday and we saw the ghost of old Mrs Reilly plain as I see you. She were there hiding among the trees, wearing a black cloak and hood but her face were right plain in the moonlight. Joan and I were afraid and ran out of the wood quick as we could, and she never came after us. But we did see her, sir, and what I speak is God’s truth.”

Joan Miller was commanded to stand up and, obviously terrified, muttered her timid agreement with Betsy’s account. Hardcastle clearly felt that he was encroaching on feminine and uncertain ground. He looked to Mrs Reynolds, who took over. “You know very well, Betsy and Joan, that you are not permitted to leave Pemberley unescorted after dark, and it is unchristian and stupid to believe that the dead walk the earth. I am ashamed that you allowed such ridiculous imaginings to enter your minds. I will see both of you in my sitting room as soon as Sir Selwyn Hardcastle has finished his questions.”

It was apparent to Sir Selwyn that this was a more intimidating prospect than he could produce. Both girls muttered, “Yes, Mrs Reynolds,” and promptly sat down.

Hardcastle, impressed by the immediate effect of the housekeeper’s words, decided that it would be appropriate for him to establish his status by a final admonition. He said, “I am surprised that any girl who has the privilege of working at Pemberley can give way to such ignorant superstition. Have you not learned your catechism?” A murmured “Yes sir” was the only response.

Hardcastle returned to the main part of the house and joined Darcy and Elizabeth, apparently relieved that all that remained was the easier task of removing Wickham. The prisoner, now in gyves, was spared the humiliation of having a group watching him taken away, and only Darcy felt it his duty to be there to wish him well and to see him put into the prison van by Headborough Brownrigg and Constable Mason. Hardcastle then prepared to enter his carriage but before the coachman had cracked the reins he thrust his head out of the window and called to Darcy, “The catechism. It does contain an injunction, does it not, against entertaining idolatrous and superstitious beliefs?”

Darcy could recall being taught the catechism by his mother but only one law had remained in his mind, that he should keep his hands from picking and stealing, an injunction which had returned to memory with embarrassing frequency when, as a boy, he and George Wickham had ridden their ponies into Lambton and the ripe apples on the then Sir Selwyn’s laden boughs were drooping invitingly over the garden wall. He said gravely, “I think, Sir Selwyn, that we can take it that the catechism contains nothing contrary to the formularies and practices of the Church of England.”

“Quite so, quite so. Just as I thought. Stupid girls.”

Then Sir Selwyn, satisfied with the success of his visit, gave a command and the coach, followed by the prison van, rumbled down the wide drive, watched by Darcy until it was out of sight. It occurred to Darcy that seeing visitors come and go was becoming something of a habit, but the departure of the prison van with Wickham would lift a pall of recollected horror and distress from Pemberley and he hoped too that it would not now be necessary for him to see Sir Selwyn Hardcastle again before the inquest.

Book Four

The Inquest

1

It was taken for granted both by the family and the parish that Mr and Mrs Darcy and their household would be seen in the village church of St Mary at eleven o’clock on Sunday morning. The news of Captain Denny’s murder had spread with extraordinary rapidity and for the family not to appear would have been an admission either of involvement in the crime or of their conviction of Mr Wickham’s certain guilt. It is generally accepted that divine service affords a legitimate opportunity for the congregation to assess not only the appearance, deportment, elegance and possible wealth of new arrivals to the parish, but the demeanour of any of their neighbours known to be in an interesting situation, ranging from pregnancy to bankruptcy. A brutal murder on one’s own property by a brother by marriage with whom one is known to be at enmity will inevitably produce a large congregation, including some well-known invalids whose prolonged indisposition had prohibited them from the rigours of church attendance for many years. No one, of course, was so ill bred as to make their curiosity apparent, but much can be learnt by the judicious parting of fingers when the hands are raised in prayer, or by a single glance under the protection of a bonnet during the singing of a hymn. The Reverend Percival Oliphant, who had before the service paid a private visit to Pemberley House to convey his condolences and sympathy, did all he could to mitigate the family’s ordeal, firstly by preaching an unusually long, almost incomprehensible sermon on the conversion of St Paul, and then by detaining Mr and Mrs Darcy as they left the church in so protracted a conversation that the waiting queue, impatient for their luncheon of cold meats, contented themselves with a curtsey or a bow before making for their carriage or barouche.

Lydia did not appear, and the Bingleys stayed at Pemberley both to attend her and to prepare for their return home that afternoon. After the disarray that Lydia had made of her garments since her arrival, arranging her gowns in the trunk to her satisfaction took considerably longer than did the packing of the Bingleys’ trunks. But all was finished by the time Darcy and Elizabeth returned for luncheon and by twenty minutes after two o’clock the Bingleys were settled in their coach. The final farewells were said and the coachman cracked the reins. The vehicle lurched into movement, then swayed down the broad path bordering the river, down the incline in the long drive and disappeared. Elizabeth stood looking after the coach as if she could conjure it back into sight, then the small group turned and re-entered the house.

In the hall Darcy paused, then said to Fitzwilliam and Alveston, “I would be grateful if you would join me in the library in half an hour. We are the three who found Denny’s body and we may all be required to give evidence at the inquest. Sir Selwyn sent a messenger after breakfast this morning to say that the coroner, Dr Jonah Makepeace, has ordered it for eleven o’clock on Wednesday. I want to be clear if our memories agree, particularly about what was said at the finding of Captain Denny’s body, and it might be useful to discuss generally how we should proceed in this matter. The memory of what we saw and heard is so bizarre, the moonlight so deceptive, that occasionally I have to remind myself that it was real.”

There was a murmur of acquiescence and almost exactly on time Colonel Fitzwilliam and Alveston made their way to the library where they found Darcy already in possession. There were three upright chairs set at the rectangular map table and two high buttoned armchairs, one each side of the fireplace. After a moment’s hesitation, Darcy gestured to the new arrivals to take those, then brought over a chair from the table and seated himself between them. It seemed to him that Alveston, sitting on the edge of his seat, was ill at ease, almost embarrassed, an emotion so at variance with his customary self-confidence that Darcy was surprised when Alveston spoke first, and to him.

“You will, of course, be calling in your own lawyer, sir, but if I can be of any help in the meantime, should he be at a distance, I am at your service. As a witness I cannot, of course, represent either Mr Wickham or the Pemberley estate, but if you feel I could be of use, I could impose on Mrs Bingley’s hospitality for a little longer. She and Mr Bingley have been kind enough to suggest that I should do so.”

He spoke hesitantly, the clever, successful, perhaps arrogant young lawyer transformed for a moment into an uncertain and awkward boy. Darcy knew why. Alveston feared that his offer might be interpreted, particularly by Colonel Fitzwilliam, as a ploy to further his cause with Georgiana. Darcy hesitated for only a few seconds, but it gave Alveston a chance quickly to continue.

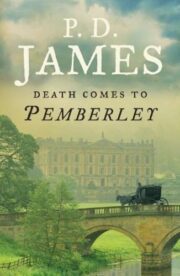

"Death Comes to Pemberley" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Death Comes to Pemberley" друзьям в соцсетях.